Introduction

The breakdown in June 2011 of talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the future of Nagorno-Karabakh has increased speculation that a war may be imminent. Some observers have even suggested that a short war in which neither side achieved victory might be welcome if it cleared the way for more meaningful negotiations. Such views reflect the belief that the present stalemate can only be broken if a limited short war demonstrates the impossibility of resolving the conflict satisfactorily by force of arms and forces the protagonists back to the negotiating table. In other words, a small war is necessary to bring lasting peace and a final resolution to a dispute that has festered for nearly two decades.

The speculation that the risk of war is growing rapidly has been fuelled by some fierce rhetoric on both sides, as well as by the announcement of

a huge increase in defence spending by Azerbaijan. Following the collapse of the talks on 28th June – the tenth attempt to resolve the dispute in 19 years – President Ilham Aliyev declared: “The war is not over yet.” Speaking on Armed Forces day at the largest military parade to be held in Baku since Independence, he added: “The territorial integrity of Azerbaijan must be restored and the territory will be restored.”

Two days later, the Azerbaijani Defence Minister, Safar Abiyev, told those passing out at a military graduation ceremony: “You should be ready to join battle to liberate occupied territories at any moment. Do not forget that the homeland expects you to display courage and fortitude.”

A few weeks after that Serg Sargysian, the Armenian President, stated: “The sooner Nagorno-Karabakh is recognised, the better it will be for

everyone, including Azerbaijan. Our goal is never to let Nagorno- Karabakh be under Azerbaijan’s rule.”

The Armenian President’s comments follow a series of similarly intemperate outbursts on earlier occasions. Speaking at an OSCE summit he stated: “Azerbaijan has no interest in settling the Karabakh issue: its sole purpose is to inflict as much damage on Armenia as possible … Nagorno-Karabakh has no future within Azerbaijan.”[ref]President Serg Sargysian, at the OSCE Meeting of the Heads of State or Government, December 2 2010. [/ref]

Inevitably, such comments suggest to Azerbaijanis that President Sargysian has been negotiating in bad faith because the Madrid Principles, which both sides have accepted as the basis for negotiation, specifically include the withdrawal of Armenian armed forces. The Washington-based Jamestown Foundation expressed a view which is held almost universally in Azerbaijan: “It is obvious that Armenia, holding some 20 per cent of Azerbaijan’s internationally recognised territory, is not willing to give it back and is simply dragging out time to win international legitimisation for this occupation.”[ref]Alman Mir-Ismael, “Kazan Summit Breaks Hearts in Baku”, Jamestown Foundation Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol 8 Issue 126, June 30 2011.[/ref]

Speculation that war may soon erupt is also strengthened by the increasing number of clashes involving Azeri and Armenian forces on the Line of Contact (LoC) running between Azerbaijan and the de facto but unrecognised state of Nagorno-Karabakh. In 2010, at least 25 lives were lost in skirmishes, up from 19 in 2009. One of the most serious ceasefire violations occurred in February 2010, with reports of multiple casualties on both sides. In the words of one commentator: “The large number of soldiers around the LoC, the proximity of the Armenian and Azerbaijani territories and the sophistication of the military hardware available to them, make occasional clashes almost inevitable. These factors also increase the chances of fatalities, raising the danger of escalating retaliatory strikes with heavier weaponry and across a larger area. Lack of direct communication between the two sides, as well as the opacity of troop movements, make it more difficult to cool down tense

situations.”[ref]Alexander Jackson, “Next Steps in the Solution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”, Caucuses

International, Vol 1 No 1, Summer 2011.[/ref]However, as the same observer noted, the fact that these skirmishes do not spill over into major conflagrations at least demonstrates that the political leadership on both sides retains control over their armed forces. Although a war resulting from a misreading of strategic intentions or other accidental factors cannot be ruled out, if war does occur it is more likely to do so as the result of a conscious political decision.

However, given the inherently unpredictable nature of modern warfare and the scale of the likely costs, it would seem that for as long as Azerbaijan believes that there is a realistic possibility that the OSCE- brokered peace talks can lead to the restoration of its territorial integrity, it will not carry out its threat to regain its lost territory by force – even if there is no let up in the war of words. Baku believes the failure of the June 2011 talks has significantly reduced – though not quite exhausted – that possibility. But having come to enjoy the benefits of rising prosperity and stability, it will not lightly take a decision to go to war. Clearly, its calculations could change if a further round of talks were to fail. Its calculations will also be influenced by further shifts in the

balance of military power between the two states; this already favours Azerbaijan and will do so in the future to an a rapidly increasing extent.

Military Realities

As a rule of thumb, military analysts have suggested that offensive forces require a three to one advantage to be confident of success. Does Azerbaijan possess such an advantage? If not, is it likely to obtain it within the near future?

The trend in terms of military spending is striking. During the present year Azerbaijan’s military expenditure exceeded that of Armenia eight- fold, amounting to $3.2 billion compared to $405 million in the other South Caucasus republic.[ref]IISS, Military Balance, 2011.[/ref]

According to the International Institute of Strategic Studies, this means that Azerbaijan’s military budget has doubled within three years and now exceeds its neighbour’s entire national budget. The Azerbaijani president has promised that there are further increases to come. By contrast, Armenia’s defence budget rose by $33 million last year, but has been hacked back by twenty per cent during the present year as the result of severe economic pressures.

Armenia, with a gross national product one-fifth the size of its neighbour, continues to spend a slightly higher proportion of its GDP on defence

than Azerbaijan (2.8 per cent compared to 2.6 per cent) but its tiny population of 3.3 million is shrinking as a result of emigration and its economy is kept afloat as the result of remittances from the world-wide Armenian Diaspora; these account for almost 20 per cent of Armenia’s national wealth.

The differences in economic strength are reflected in the differences in military capabilities. According to the IISS, Azerbaijan’s armed forces consist of 56,840 ground troops, 2,200 navy and 7,900 air force officers. Armenia has 45,903 ground troops and an air force comprising 3177 military personnel.[ref]IISS, Military Balance, 2011.[/ref]

Azerbaijan also has three times more battle tanks – 339 compared to only 110 for Armenia. It has a marked superiority in terms of armoured vehicles and artillery units, and possesses nearly three times as many warplanes as Armenia – 41 compared to 16. Azerbaijan also has many more infantry combat vehicles[ref]ibid.[/ref]

However, these figures do not take account of the Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army which is closely linked to Armenia’s armed forces and is fully integrated in its command and control structures. This is often said to be around 20,000 strong, well trained and well equipped, but the original source for this estimate, accompanied by accounts of the high morale and military effectiveness of these forces, appears to be an article in a magazine published by US-based members of the Armenian Diaspora.[ref]Richard Giragosian, “Armenia and Karabakh: One Nation, Two States, AGBU Magazine, No.1 Vol 19, May 2009. [/ref]

Since the Diaspora takes a hard-line position on the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh, vociferously opposing any concessions in the ongoing OSCE talks, this may well have an interest in exaggerating the size and capabilities of those forces. However, independent analysts have suggested that given Karabakh’s current population amounts to only 140,000, the number of servicemen there could not exceed 7,000-8,000.[ref]“Azerbaijan’s military more powerful than Armenia’s: think tank”, Azernews.az, 17 May 2011. [/ref]

The Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army’s heavy military hardware is believed to include 371 tanks, 459 armoured vehicles, 322 artillery pieces of calibres over 122 mm, 44 multiple rocket launchers, and a new anti- aircraft defence system. In addition, the NKR Defence Army maintains a small air force of 2 Su-25s, 5 Mi-24s and 5 other helicopters.[ref]Based on data from Hans-Joachim Schmid, “Military Confidence Building and Arms Control in Unresolved Territorial Conflicts,” Peace Research Institute, Frankfurt Reports, No. 89. [/ref]

Nikolay Bordyuzha, Secretary General of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, the Russian-led security organisation which includes Armenia and five other CIS-states, has praised the general quality of Armenian armed forces: “I was present at many exercises and saw the Armenian units, which are not numerous but well trained and rallied by a high moral spirit.”[ref]PanArmenian.Net, February 16 2007. [/ref]

However, it should be borne in mind that three quarters of the Armenian armed forces are conscripts and that many young people go to great lengths – including the payment of bribes – to avoid being conscripted. According to a survey, around 30 per cent of Armenians attending university say they do so in order to qualify for exemption and of these 65 per cent reported that they had offered bribes in to gain their university places.

In order to cope with an expected shortfall in conscripts resulting from a fall in the birth rate in the 1990s, the Armenian government is reported to be considering removing university enrolment as a reason for exemption. Such factors suggest that reports that the Nagorno- Karabakh Defence Army displays a high level or morale and combat readiness should be treated with a measure of scepticism. A further reason for doubting the cohesiveness and effectiveness of the NK Defence Army can be found in reports of non-combat deaths and other

violent incidents in the ranks, as a result of institutionalised bullying. In a report released in February 2011, the human rights group, Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly, claimed that 42 Armenian soldiers died in 2010, and that only nine of them were shot during exchanges with Azerbaijani forces, while more than half of them were murdered by fellow servicemen. Military analysts are agreed that bullying damages morale and prevents the development of an esprit de corps.

Whatever the quality, quantity and morale of Armenia’s military personnel there are other factors which Azerbaijan’s military planners will need to take into account; these will influence their assessment of the character and numerical superiority which will need to be displayed by a successful Azeri offensive.

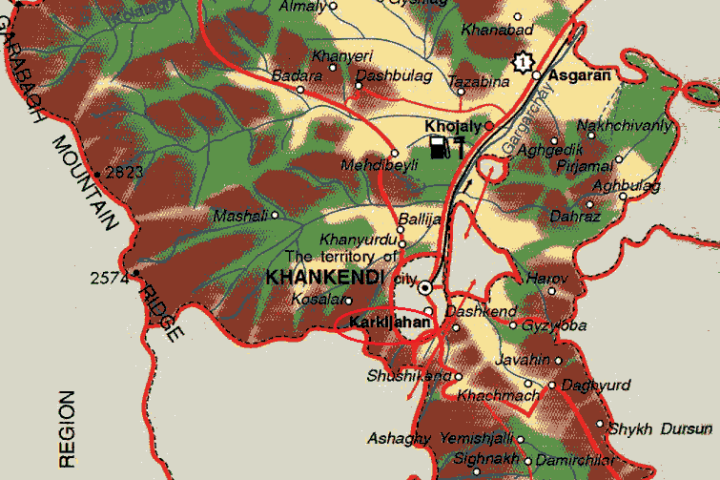

The most obvious of these has to do with the region’s topography. Karabakh’s mountainous terrain, where NK forces known to be well dug- in, makes the task of seizing and holding territory problematic. Meanwhile, the need to pacify a hostile civilian population would also present additional challenges for the Azeri armed forces. As a recent article in the Caucasian Review of International Affairs noted, topography may be a key factor in explaining the lack of a major conflict since 1994[ref]Alexander Jackson, “The Military Balance in Nagorno Karabakh”, CU Issue 18, January 19 2009. [/ref]

The ceasefire line currently runs through rugged, mountainous terrain topped with multiple defensive lines which would favour the Armenian side in a war launched by Azerbaijan. As its author pointed out, Azerbaijan’s purchase of 25 Su-ground attack aircraft from Georgia and unmanned aerial vehicles from Israel should be interpreted as an attempt to compensate for the likely difficulties faced by its ground artillery.

There are also difficulties and imponderables at the political level. It is unclear what role if any Russia would play in such a situation.

Armenia and Russia signed a defence deal on 20th August 2011 extending the presence of a Russian military base in Armenia until 2044. The deal amended an existing bilateral treaty signed in 1995 that regulated the presence of the Russian military base in Gyumri, Armenia’s second

largest city. The amended agreements also commit Moscow to upgrading the mission of its troops stationed in Gyumri, as well as providing Armenia with modern military equipment at reduced prices. In 2010, more than 3,000 troops were based at Gyumi while military hardware included 74 tanks, 201 combat vehicles and 84 artillery units.

Under the terms of a mutual defence clause contained in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, Russia is committed to defending Armenia in the event of an attack on its territory. Armenia has periodically asked for, and obtained, specific assurances that it would intervene in the

event of an attack on its territory by Azerbaijan. It has also stated that it would regard an attack on Nagorno-Karabakh as an attack on itself, but Russia, in common with the rest of the world, does not recognise Nagorno-Karabakh as an independent state. It is clear, therefore, that the Russian guarantee does not extend to territory that still legally part of Azerbaijan. Moreover, the extension of CSTO guarantees would be incompatible with its role as co-chair of the Minsk Group, which was set up under the auspices of the OSCE in 1992 to achieve a settlement of the dispute.

In contravention of an OSCE resolution of 1992 banning arms sales by participating states to both parties to the dispute, Russia has sold arms to both Armenia and Azerbaijan, a fact which has confirmed suspicions that it is largely content with the present stalemate and is more interested in managing relations between Yerevan and Baku in its own interests than it is in resolving the dispute between them.

Significantly, Azerbaijan’s new S300 surface-to-air missile system, recently purchased from Russia, has sufficient range to cover the whole of the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, and much of Armenia, but not the Russian military base at Gyumri. Russia at first denied selling the missiles, which would provide protection against Armenia’s Scuds, but gave up doing so when the missiles were given pride of place in a military parade in Baku in June this year. If war breaks out, Armenia’s Russian missiles and Russian planes would consequently be targeted by Azerbaijan’s Russian missiles. Providing that the conflict was confined to Karabakh and did not spread to Armenia proper, Russia might conclude that its interests would be served by remaining out of the conflict, although it would not wish to see its closest regional ally militarily humiliated. For the time being at least, its interests lie in keeping alive Azerbaijan’s hopes of a peaceful settlement, with President Medvedev continuing to play an energetic if somewhat disingenuous role as peacemaker.

One consequence of the OSCE ban on weapons sales is that both countries have begun to develop their own armaments industries, although it is clear that Azerbaijan is better placed to do so than Armenia and is making far more progress.

Earlier this year, the Russian magazine Argumenti Nedeli (The Week’s Arguments) reported that Azerbaijan and Turkey had agreed to jointly produce infantry rifles and 105 mm cannons with the possibility of cooperation in the production of larger calibre weapons. The same issue of the magazine reported that Azerbaijan is planning to build its own guided anti-tank missiles and that it has been invited to participate in a Turkish project to develop Altay main battle tanks.

Azerbaijan has already purchased and deployed Israeli-built drones. But during the visit of the Israeli President, Simon Peres, to Azerbaijan in June 2009, Azerbaijan signed a preliminary agreement with the Israeli Aeronautics Defense Systems Ltd to construct a plant to manufacture reconnaissance and unmanned military aircraft, as well as spy satellites. On 19th September 2011 Azerbaijan took delivery of 600 Israeli-designed Orbiter and Aerostar unmanned vehicles, which were built by Azeri companies.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has begun production of the most recent model of Russia’s Kalashnikov assault rifles.

Anxious that its own contribution to this arms race should be taken seriously, Armenia has responded by adopting its own four-year programme to develop indigenous weapons systems, providing not only for the manufacture of weapons but also the development of “an Armenian military industrial complex.” Given the daunting economic problems faced by Armenia and its almost total reliance on Russian weapons, this is an ambition that may never get off the ground. However, in June 2011 a high-ranking member of the Armenian air force claimed that his country was building its own “quite serious” unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), although he did not rule out also purchasing foreign made UAVs.[ref]RFE/RL report, June 21, 2011. [/ref]

Realistically, in the present arms race between Armenia and Azerbaijan, there can only be one winner, and without the supplies of Russian weaponry there would not even be a race. As a result of the factors described earlier and the difficulty in obtaining reliable data regarding the size and competence of the Nagorno- Karabakh Defence Army, it is unclear whether Azerbaijan could swiftly prevail in a military campaign to restore its territorial integrity if such an offensive was launched today. What seems reasonably clear is that it is will be in a position to do so in the near to mid-term.

Wider Considerations

Arms races are the reflection of deep political conflicts and, contrary to much rhetoric on the subject, it is a mistake to regard them or the military industrial complexes that support them as the causes of wars.[ref]For a discussion of this topic, see Michael Howard, “The Causes of Wars”, Temple Smith, London, 1983. [/ref]

Wars happen when one or more of the parties involve decide that they have more to gain by going to war than by pursuing their aims by other means. The present conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia exemplifies these truths. It is possible to imagine circumstances in which, frustrated by lack of progress in the peace talks and having taken further steps in modernising its armed forces, Azerbaijan takes military steps to regain territory that was seized by military means. That point has not yet been reached but Baku recognises that it may be reached in the foreseeable future. In the meantime, it has every interest in intensifying the arms race with Armenia and in drawing attention to its growing military superiority as way of adding to the pressure on Armenia to make concessions at the peace talks. In a strictly military sense, time is on Azerbaijan’s side, but it is conscious that time is not on its side in a political sense. A further decade of meaningless and wholly

unproductive talks would give Yerevan the opportunity to gain legitimacy for the breakaway republic of Nagorno-Karabakh and make it harder for Baku to win international support for military action. Hence its decision to double the defence budget in a mere three-year time span,

and to go on spending at a similar rate. Given the time constraints described above, Azerbaijan’s military build-up must continue at the same rapid pace if the threat of war is to be credible as a way of forcing Armenia to adopt a more conciliatory negotiating position. Care must also be take to avoid the impression that Baku’s escalation of the arms race is not seen merely as a negotiating tactic but reflects an unchanging determination to do whatever is necessary to restore it lost lands. This imperative explains the bellicose statements emerging from Baku of a kind that often grate on Western ears.

Thomas de Waal, a distinguished analyst specialising in the politics of the Caucasus, has consistently urged both Armenia and Azerbaijan to acknowledge the mistakes of the past, to compromise and to end the current war of words between them as the first steps in reaching a peaceful settlement to the dispute.[ref]Thomas de Waal, ‘More War in the Caucuses’, National Interest, February 9 2011. [/ref]

Similar advice has been offered by a wide variety of US and European leaders, including Catherine Ashton, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs.[ref]Speech to the European Parliament at Strasbourg on July 6 2011.[/ref]Inevitably, both parties find such advice difficult to follow, both for cultural and historical reasons. For Azerbaijan such assertions would also present practical difficulties in achieving its central policy aim, which is to right an historic wrong – a wrong that has been acknowledged by the international community in the form of four UN resolutions – and to bring to an end a major humanitarian tragedy. Baku understandably fears that a softer, more conciliatory tone would be taken in Yerevan as a signal that it was reducing demands which have already been accepted by the international community. It might also be taken as an indication that it has privately ruled out the use of force as a means of restoring its former borders, even as a last resort.

Baku also resents the fact that many Western appeals for an end to the war rhetoric are couched in terms that suggest some kind of moral equivalence between the parties to the dispute. This, it points out, is not borne out by the facts. It was Azerbaijan, not Armenia, which lost most of the war dead in a conflict that claimed 300,000 lives, which lost twenty per cent of its territory, and which continues to support more than 800,000 displaced persons who are prevented from returning to their homes because Yerevan alleges that it would not be safe for them to do so. But it is Armenia, not Azerbaijan, which refuses to accept the terms of UN resolutions requiring the withdrawal of its military forces.

Azerbaijani public sentiment on these issues and the approach of a general election in 2013 suggests that there will be no let-up in the diplomatic offensive to explain the Azeri position. Azerbaijanis believe that, thanks largely to the Armenian Diaspora, their neighbour has been far more effective in getting its message across – and consequently there will be no halt in the war of words with Armenia. Nor is there likely to be any restraint on the Armenian side. The approach of an election in 2012 and the centenary of the Armenian holocaust in 2015 suggest a period of heightening tensions between the two countries.

The optimists among public policy analysts believe that the prospects for progress in the peace talks resulting from a greater readiness to compromise by the Armenian side could be significantly better post-2015. Given Armenia’s chronic economic difficulties and its nightmarish demographic profile, it has a powerful incentive to take measures, however unpalatable, which would lead to the opening of its border with Turkey. This would bring a badly needed boost to trade prospects and a reduction of its dependency on Russia.

In the past there have been signs that, despite past intransigence, Yerevan would be prepared to accept a deal that had the backing of the international community and which brought tangible economic rewards. In 2008 Levon Ter-Petrosyan, the then Armenian President, accepted just such a deal only to be forced to resign following opposition to the plan from within Armenia, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh and the Armenian Diaspora, which enjoys considerable influence on the Yerevan government as a result of its remittances to the homeland.

As President, Ter-Petrosyan had been regularly vilified by the Diaspora as a result of his attempts to normalise relations with Turkey and his refusal to make genocide recognition a priority in his talks with that country. As the New York Times noted in its issue of 12th February 1993, which also carried an interview with the then Armenian President:

“Besides his domestic critics, Mr. Ter-Petrosyan must deal with an aggressive minority in Armenia’s powerful diaspora, which regards anything less than total victory in Nagorno- Karabakh as capitulation to the hated ‘Turks’ — a word that many Armenians use for both Turks and Azerbaijanis.

“With 3 million Armenians living in the West and 3.5 million more living in the other countries of the former Soviet Union, Armenia — like Israel before it — has had to sort out its delicate relationship with a Diaspora that sometimes sees financial and relief aid as a license to influence internal politics.”

As the New York Times pointed out, Mr Ter-Petrosyan responded to this situation by introducing a law that banned foreign based parties and organisations from direct participation in Armenian politics – but it was a law that went uninforced.

Commenting on the extrme positions taken by Disapora organisations, Mr Ter-Petrosyan told the New York Times:

“It is just that we lived different lives, Armenia and the diaspora. Here it is real politics, while the diaspora lives with the ideas of unreal politics, and they cannot change their ideas so quickly.”

Mr Ter-Petrosyan’s political fall could well discourage other would-be Armenian peacemakers – especially since Armenia’s dependence on the Diaspora is probably greater than it has ever been. Indeed, the role the Diaspora in influencing political developments in the former homeland does not bode well. Although fuelled by a similar sense of victimhood and a highly selective reading of history, statements by leading members of the Diaspora, especially but not exclusively in the US, show a more

extreme strain of nationalism than that displayed by members of Armenia’s shrinking domestic population, while taking less account of economic and political reality.

As Armenia’s creaking economy has floundered, the Diaspora has come to exert a yet greater influence and has recently been offered a say in the

decision-making process through plans to create a second parliamentary chamber in which it would be directly represented. Given the intemperate character of many statements by members of the Diaspora, this development is likely to be viewed with some concern in Baku.

An interesting analogy

Although such comparisons can be misleading, parallels can be drawn between the influence of the Armenian Diaspora and that of the Irish Diaspora prior to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement of February 1998, at which time Sinn Fein/IRA effectively abandoned its armed struggle for Irish Unity.

Like the Armenian Diaspora, Irish Republican organisations in the United States had sought to influence American policy (which in practice meant seeking legitimacy for a vicious campaign of terror). Like its Armenian counterpart, the Irish Diaspora exploited a semi-mythical reading of the past as well as a sense of historic injustice and victimhood. Like the Armenian Diaspora, the total number of Irish émigrés was not huge in comparison to other ethnic groups but was heavily concentrated in particular US cities – notably Boston, New York and Chicago – in which it was able to influence the selection of Congressional candidates as well as the voting behaviour of those elected.

Using the widespread affection for Irish history and culture, and exploiting considerable ignorance of the wider population and indeed that of Irish émigrés themselves about the realities of the situation – for example, contrary to popular American myth the majority of Irish- Americans are actually of English Protestant descent – NORAID, the largest of the IRA support groups, raised large sums of money to fund IRA terrorism as well as engaging in intensive lobbying and propaganda.[ref]In 1981 Noraid suffered a major setback when the US government won a court case which resulted in Noraid being forced to register the IRA as its “foreign principal.”[/ref]

It is a striking fact that Sinn Fein, the so-called “political wing” of the IRA, only became interested in adopting peaceful ways of achieving its objectives after the events of September 11 2001 produced a general revulsion for terrorism of all kinds and so put Noraid out of business, thereby depriving the IRA of its main source of funds. It has since been eclipsed by “Friends of Sinn Fein”, an organisation founded by American businessmen whose charter ensures that the organisation’s much more modest funds can only be used for political activity.

If there are lessons to be drawn from the Irish experience it is that diasporas, which by their nature are far removed from the realities of the political lives of their home nations, can help foster and sustain violent or unreasonable behaviour and discourage reconciliation and compromise, especially where such conduct is fuelled by a strong sense of historic injustice.

Conversely, events which for whatever reason reduce the political influence of radical émigré groups can lead to changes in the political climate that make conciliation and compromise more acceptable policy options. It is presently difficult to imagine circumstances in which the Armenian Diaspora suddenly suffer a loss of influence comparable to that experienced by Irish Republicans in the US post-September 11th. But it is possible to imagine circumstances that might result in the loss of some measure of its present influence. These could include the replacement of the present government in Yerevan by an administration that, for whatever reason, was less willing to accommodate its wishes. They might also include a systematic campaign by the Azerbaijanis to blunt the effectiveness of Armenia’s lobbying and propaganda drive by propagating its own message on Nagorno-Karabakh more effectively. This could achieve a significant breakthrough at a time when Azerbaijan’s international importance is becoming more apparent as a result of its booming energy sector, its rapid economic growth and its policy of international engagement.

The Future Pattern of Events

The next five years will witness still greater disparities in terms of economic and military power between Azerbaijan and Armenia than exist at the present time. These will become more apparent as tensions between the two countries increase.

To date, the international community has done little to give practical expression to the four UN Resolutions calling for the withdrawal of Armenian troops and the restoration Azerbaijan territorial integrity. While there is no clear indication that this situation is about to change, Azerbaijan’s growing role as a net energy exporter and its readiness to open up a southern energy corridor that reduces Europe’s dependency on Russian gas should at least ensure a sympathetic hearing of its case in Western Europe and the US. At the diplomatic level, Azerbaijan will wish

to underline that European and US interests will scarcely be served by a conflict that could threaten energy supplies. It is also likely to adopt a much more pro-active role in seeking to respond to the propaganda war to which has been subjected by Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora.

Russia, by far the most influential of the outside powers in this dispute, is widely assumed to have concluded that its own interests are served by ensuring that the present conflict remains frozen. Were it to conclude that the present stalemate is not merely unstable but on the verge of collapse, this could change. Russian interests would not be served by

the military humiliation of its principle regional ally or by the emergence of a stronger Azerbaijan over which it would be able to exert diminished

influence. In such circumstances, the EU and the US could join Russia in bringing pressures on Armenia to make meaningful concessions at the conference table in order to avert war while offering a range of inducements and security guarantees.

If, however, nothing changes in the next three to four years, if Yerevan, encouraged by the Diaspora, continues to adhere to its present hard-line nationalist position, and if the international community fails to take a more active role in pressing Yerevan to make meaningful concessions, the prospect of war is bound to grow; indeed war may very well prove to be inevitable.