Since 1988, that is, since the beginning of the Karabakh events the interested parties (states, international organizations) as well as individuals (statesmen, political scientists) and many public and political organizations have put forward different proposals for the solution of the Karabakh conflict. In the present chapter we attempt to offer as full an account as possible of these proposals according to the following scheme:

1.The international-legal aspects of the problem

2.The possible schemes of principles for the resolution of the problem.

The international-legal aspects of the Karabakh problem ought to, one might think, make their own decisive contribution to its solution. However, they, in their turn, have come to be part of the conflict between two major principles – the right of nations to self-determination versus the principle of territorial integrity and inviolability of state borders, two principles which the opposing sides and often third parties in the conflict interpret to serve their own interests1. It is natural to note that the situation which formed in international law after the Second World War is at least associated with the inconsistency of the world community itself which lags behind in its legal assessment of political processes in various parts of the world. To completely assess the situation, it’s quite enough to turn to the source we ourselves refer to in our analysis of the international-legal aspects of the conflict, i.e. the articles by E. Kurbanov, “International Law on self-determination and the conflict in Nagorni Karabakh”; A. Iskandaryan, “The genesis of post-communist ethno-political conflicts and International Law (Trans-Caucasus as an example)”; and N. Hovhannisian, “The Nagorno Karabakh conflict and variants for its solution”, presented in the book “Ethno-political conflicts in Trans-Caucasus: their sources and ways to solve them” Published by Maryland University, 1997.

On the face of it these two principles are indeed incompatible in cases where the population residing on the part of the territory of a certain state declares its intention to secede from its membership, that is, to subject the borders of this state to changes. The universal solution of such kind of conflicts could be found, it would seem, if the international community were to come to the opinion that one of these principles took primacy over the other. But there isn’t a proper judgement on this question, and it compels us to seek various solutions in every concrete case.

Many researchers note that the preference given by international actors to one or another of the aforementioned principles often changes depending on the prevailing political state of affairs. For instance, during the cold war, evidently, the principle of non-violation of borders and territorial integrity dominated in international relations. The world at that time was divided into two opposing hostile military-political blocks headed by the USA and the USSR respectively. Each side was afraid that any changes in the world proceeding from the right of self-determination could affect the already established balance of forces.

An exception was observed for the peoples under colonial rule. As far back as in 1960 the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a Declaration about decolonization which embraced absolutely all colonial peoples. At the same time it should be noted that even in that period there were cases of secession and formation of new states on the part of non-colonized peoples, for instance, Bangladesh, Singapore and Eritrea.

The situation changed after the cold war, the collapse of the USSR and the elimination of the socialist camp. Since this time discussions about a new world order, requiring different approaches to the question of a correlation between the right of self-determination and the principle of territorial integrity, have begun. The essence of the new situation is formulated by American researchers M. Halperin and D. Sheffer: “With the end of the cold war the international community ran unexpectedly into multiple demands of peoples for self-determination in the context of different forms (variants). The clear principles, which served as guidelines during the confrontation with the Soviet Union, have disappeared and it is impossible any more to state that all existing states must be unique and no changes can take place in international borders”2.

There are, it would seem, no more grounds to set up an opposition between self-determination and the principle of inviolability of state borders. The above mentioned authors note that it is time to pursue “a creative policy which would take into account the peculiarities of each situation”3

In their opinion, a demand for self-determination may reflect a legitimate aspiration, which shouldn’t be ignored, and in most cases such wishes can be realized within the borders of the existing states, but in some cases there is a necessity for the formation of new states and a peaceful procedures for changes towards secession, that is to say, for separation must be offered.

Modern conflictologists, the supporters of a new approach to the problem of self-determination and inviolability of state borders, have done useful work from the viewpoint of classification of demands for self-determination:

A. Anti-colonial self-determination. This means a solution of a problem according to the Declaration of the UNO 1960. Arguments hardly ever arise in connection with this category of self-determination.

B. Sub-state self-determination. This implies the aspiration of ethnic groups in an already existing state to secede from its membership and to form a new state. This category includes Tibet in China, the Sikh community in Punjab (India), Chechnya in Russia, Corsica, striving to secede from France, etc.

C. Trans-state self-determination. This case can be applied to groups of peoples, residing in more than one country. The researchers note that “a group (people) may strive to break off from one and enter another state. An example is the ethnic Armenians of NK, striving to become a part of Armenia”4. This category also includes some movements in Kashmir in favor of uniting with Pakistan, the movement in South Ossetia, striving to unite with North Ossetia, which is a part of Russia, or Russians in the Crimea and Pridnestrovie, striving to secede from the Ukraine and Moldova and to unite with Russia, and also the Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina, striving to uniting with Serbia, Irish Catholics in Northern Ireland, trying to re-unite with the Republic of Ireland, etc.

Among other categories of self-determination should be noted the self-determination of dispersed peoples, the self-determination of aboriginal peoples (Guatemala, Nicaragua, Mexico, Rwanda, Australia, etc.) and representative self-determination, which is associated with the change of the political structure of a given state.

For the solution of the Karabakh problem the greatest interest from the point of view of the Armenian side are presented by the following variants of self-determination: the anti-colonial ( since the officials of the Armenian side affirm that NK had never been part of the Azerbaijan Republic of its own will), sub-state and especially trans-state self-determination.

At present a more tolerant attitude — compared with the period of the cold war – towards people striving for self-determination is apparent. And, in the opinion of Armenian experts, it is time to give up the opposition of the principles to one another. Contradictions are not intrinsic to them but lie in their interpretations. In the opinion of A. Yenokyan: “The principle of inviolability of borders prohibits near-border conflicts, the seizure of the territory of one existing state by another existing state, that is to say, it vetoes local conflicts. The principle of national self-determination acknowledges as something of high value the right of a free community of free people – the people – to have their own sovereign political formation – an independent state – and with this lofty aim it doesn’t prohibits wars”5. According to the opinion of Azeri experts, the Karabakh conflict exhibits quite transparently the seizure of the territory of a neighboring country and an attempt to present it as self-determination.

The Armenian side alludes also to the work of a German lawyer O. Lukhterhandt, ” Nagorno Karabakh’s Right to Independence According to International Law”6. He acknowledges that there is a certain contradiction between these two principles and notes that the principle of sovereignty finds its restriction in the right of self-determination and, on the other hand, the right of self-determination is restricted by the principle of sovereignty, that is to say, they balance each other. However, this researcher is convinced that any conflict or confrontation can be solved by means of differentiation between a normal case and an exceptional one. In a normal case the primacy of the principle of sovereignty is applied as a decisive basis for international law on the whole. “The exceptional” cases require a different approach. “In exceptional cases,” writes Lukhterhandt, “that is, when a national minority is discriminated in an unbearable form, then the right of self-determination in the form of the right of secession has a priority over the sovereignty of the concerned state. In the case in question the right of Azerbaijan to sovereignty loses its weight in comparison with the right of self-determination (the right of secession), because Azerbaijan itself has just become free of the dissolved USSR, taking advantage of its right of self-determination”.

Consequently, the compensatory granting of the status of a national minority which could be justified in other cases is, in the opinion of the German lawyer, inappropriate for NK. Lukhterhandt underlines that the “analysis of the policy of Azerbaijan in relation to NK as well as the conditions of life in the region shows that from the administrative, national-cultural, social-economic and demographic points of view the Armenian ethnic minority was an object of permanent and mass discrimination which lasted for decades. The state of Azerbaijan lost the right to subject the Armenian ethnic group of NK to its sovereignty”. These circumstances create the prerequisites to consider the problem of NK to be an exceptional case. It means that the right of NK to secession obtains primacy over the principle of the inviolability of the borders of the Azerbaijan Republic. As a result O. Lukhterhandt comes to the following conclusion: “On the whole an expert study of the material allows us to state that in conformity with current international law the Armenian ethnic group of Nagorni Karabakh has a right to self-determination in the form of secession from the Azerbaijan Republic (the right of secession), which has priority over the right of Azerbaijan to sovereignty. Owing to the right of self-determination, the Armenian ethnic group of NK has a right either to form its own state or to unite with the Republic of Armenia”7. For Azerbaijan, these inferences are one-sided and unconvincing. Proceeding from this logic, the Azeri ethnic group that earlier lived as a contiguous community in Armenia and was banished from there has a right to form its own state or to unite with the Azerbaijan Republic.

In the context of the problem of reconciling the two principles Armenian experts note one fact – quite important for them – which is directly related to the problem of NK. For instance, it is noted that the leaders of Armenia including the present president Robert Kocharian also come out in favor of the principle of inviolability and underline that the self-determination of Nagorni Karabakh doesn’t run counter to the principle of the territorial integrity of the Azerbaijan Republic. They believe that NK has never been a part of the independent Azerbaijan Republic – either in 1918-1920 or after the disintegration of the USSR (NK declared independence in September 1991, three months ahead of the cessation of the existence of the USSR). Azerbaijan presumes this approach to be a free interpretation of both the real historical events and international principles, which invariably acknowledge NK in the structure of the Azerbaijan Republic.

The Azeri side considers the Karabakh conflict entirely from the angle of Armenia’s territorial claims and hence insists that this question, within the framework of international law, throws up no contradictions and that there is no clash of principles. The conflict must be considered entirely within the framework of the international principle of the integrity of the state within the borders which were recognized by the international community when the Azerbaijan Republic as admitted to the United Nations in the administrative borders of the union republic (the former Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic). But as to the disputed problem of self-determination, it is noted that in all international documents there are clauses which completely remove its primacy. Thus, all international documents on self-determination contain a clause according to which “nothing in this document can be interpreted as violation of the territorial integrity of a state”. On the other hand it is said that “at present the world community recognizes only the internal aspect of self-determination – the right of the existing states to restore (recover) their independence, if they are occupied or conquered by alien forces”8.

Azerbaijan also refuses to discuss the allegedly lawful grounds of NK’s secession from the structure of the Azerbaijan Republic, adding that the so-called referendums were held without the Azeri population and in conditions which resulted after the ethnic cleansing of the region. Therefore, for all the main territorial confrontation between Azerbaijan and Armenia, the existing problems of the future status of NK must be regulated between the two ethnic groups.

The Azeri side recalls that today nobody in the world at the state-level, including the Republic of Armenia, has dared to recognize NK as an independent state, whereas the territorial integrity of the Azerbaijan Republic is recognized by all international documents. After the recent statement of presidents Bush and Putin about the search of peace in the framework of the territorial integrity of states involved in ethnic-political conflicts, the Azeri position enjoyed new support.

In the light of all the above, the viewpoint of a number of experts, who believe the legal approach to finding a solution to the problem of NK is a dead end, seems important. They, in particular, point out that international law contains many principles which can often contradict each other. V. Kazimirov, the former Russian representative of the Minsk Group speaking at the conference “Formation of Environments for Peace, Stability and Trust in the South Caucasus”, on April 25 in Yerevan commented: “I always said to the sides concerned: “God forbid that you should seek a solution in the sphere of law. It is a deadlock. The solution can be found in the political sphere only. You may like it or not but the solution of the Karabakh conflict will never be purely juridical, it is likely to be mostly political”9. It is quite another matter how much this political decision will have legal power for the future generations of the two republics.

In this chapter we took as our aim to bring together all possible variants for a political resolution of the problem of NK. We also tried as much as it is possible to evaluate the possibilities of realization of these variants.

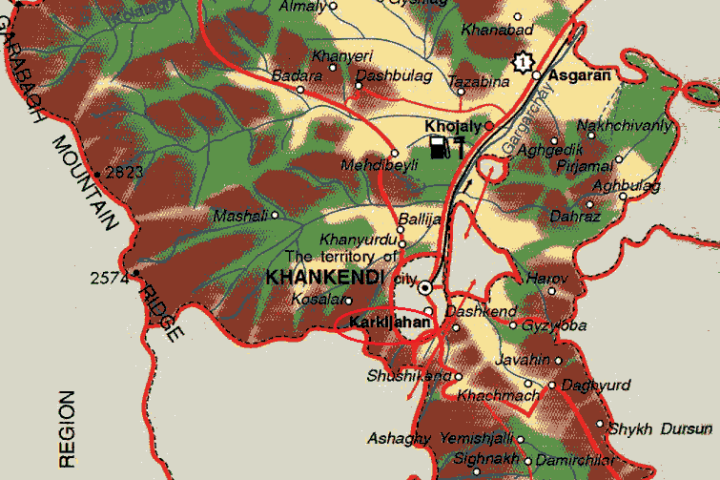

1. The position of Azerbaijan consists in the fact that the conflict which began in 1988 was the result of the military aggression carried out by Armenia against Azerbaijan with the aim of seizing and uniting part of the territory of Azerbaijan to Armenia. As a result of the aggression Armenia seized territories outside the borders of NK, hundreds of thousands of inhabitants from six regions of the Azerbaijan Republic have become refugees. Azerbaijan demands, as initial measures, the withdrawal of Armenian military formations from the occupied territories as well as a return of refugees to their homes. The Azerbaijan Republic is ready to grant NK the highest status of self-government within the structure of the Azeri state, the form and the degree of which are not specified and must be worked out in the course of negotiations.

The main point, according to this position, is the maintenance of the territorial integrity of the Azerbaijan Republic, a recognition of the Azerbaijan Republic within the borders of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. This question is not subject to negotiation. As to the de facto independence of NK ( the existence of the unrecognized NK Republic), the Azerbaijan Republic believes it to be entirely the result of aggression on the part of the Republic of Armenia.

2. The position of the Azeris of Nagorni Karabakh is rarely voiced but its official version on the whole coincides with the position of the leaders of Azerbaijan. Another viewpoint is displayed by the Organization for the Freedom of Karabakh (OFK), representing those who directly suffered from the conflict. OFK’s viewpoint on the solution of the Azeri-Armenian conflict consists in the necessity of military forces quitting the occupied lands as soon as possible and the return of the refugees to the places of their former habitation After leaving the occupied territories discussions must start, for the achievement of stable peace between the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia, on the possibility of the formation of structures of self-government for the Armenian population of the Azerbaijan Republic on the territory of Azerbaijan and of the Azeri population, driven away from the Republic of Armenia, on the territory of Armenia. This would require bringing to the table all the resources of international organizations including the United Nations, OSCE, the Council of Europe, as well as forums for civic diplomacy and human rights organizations.

OFK presumes that the main principle of the structures, securing the peaceful co-existence of Azeri and Armenian populations on the territories of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia must be the following: a complete coincidence of the statuses of administrative rights and powers of the structures formed in the Republic of Armenia and the Azerbaijan Republic.

After the achievement of an agreement with the Republic of Armenia a plan of realization of that agreement is elaborated to start measures for its simultaneous and from that point on parallel implementation in both republics.

OFK believes that a stable peace in the region is possible only if the conflict finds a just solution. The world community will be able to live in a stable and just flourishing world only if there are neither victors nor vanquished, if nobody is able to profit from the results of ethnic purges and aggression.

3.The position of the authorities of Nagorni Karabakh: acknowledgement of NK’s right of self-determination, going as far as the formation of an independent state.

The leadership of NK gives priority to the question of status in its approach to the solution of the conflict. In short, it believes that according to all clauses of International Law NKR must be recognized as a lawfully formed independent state. In particular:

- There were no legal grounds for the inclusion of NK in the structure of Azerbaijan, except a certain resolution of the Caucasian bureau of the Bolshevik party in 1921.

- For all this, even from the point of view of Soviet laws which were in effect at the time of NKR’s September 1991 declaration of independence, this act is legally beyond reproach. The declaration of NKR was in complete conformity with the Decree of the USSR of April 3, 1990, “About the order of solution of questions connected with secession of the Soviet Republics from the USSR” and was implemented on the basis of a referendum and other democratic methods, acknowledged by the world community, in the presence of large numbers of international observer on December 10, 1991.

- NK rejects any attempts to restore the status quo ante and extension of the jurisdiction of Azerbaijan to it. The leadership of NKR believes that they won a military victory and the armed forces of Azerbaijan were defeated. And this fact must be taken into account when it comes to a solution of the question of the status, because there is no historical precedent for a victor accepting the dominance of the defeated country. The relations between NK and the Azerbaijan Republic can only be of a horizontal character with certain modifications.

- The independence of NK and the achievement of such a degree of security which would ensure the preservation of the Armenian population of Karabakh. It is natural that the Karabakh army should be the main safeguard of the security of the republic and its Armenian population.

- The declaration of NKR as an independent republic means that its integration with the Republic of Armenia is not on the agenda. The leadership of NK regards this fact as a manifestation of a compromise, showing its readiness to remove the tension in the question of the integration of two Armenian states, which is regarded warily by Azerbaijan. Having said that, NKR does not hide the fact that its eventual goal is integration with the Republic of Armenia (This was once more stated by the leader of NK Arkady Ghukasian in March 2002).

The matter of the return of the territory occupied by the Army of Karabakh must be tied to the question of the status. That is, according to the formula, “land in exchange for status”.

This variant, which the Republic of Armenia and NK put forward in the initial “Soviet” period of the development of the crisis, needs no additional commentary. The present stand of the Republic of Armenia is as follows: it consents to any kind of solution of the Karabakh problem, which is acceptable to the Armenians of NK, and the same goes for the question of the status. Proceeding from this, the leadership of the Republic of Armenia doesn’t demand or insist on uniting NK with the Republic of Armenia. Therefore, the resolutions of the Republic of Armenia and NK Parliaments of December 1989 about the integration of NK and the Republic of Armenia remain on paper only (which, by the way, gives extremist Armenian politicians grounds for criticizing the Armenian government). This fact as well as the fact that the Republic of Armenia doesn’t officially recognize the independence of NKR are intended to ease the situation, to maintain room for maneuver and to leave themselves a loop-hole for political negotiations.

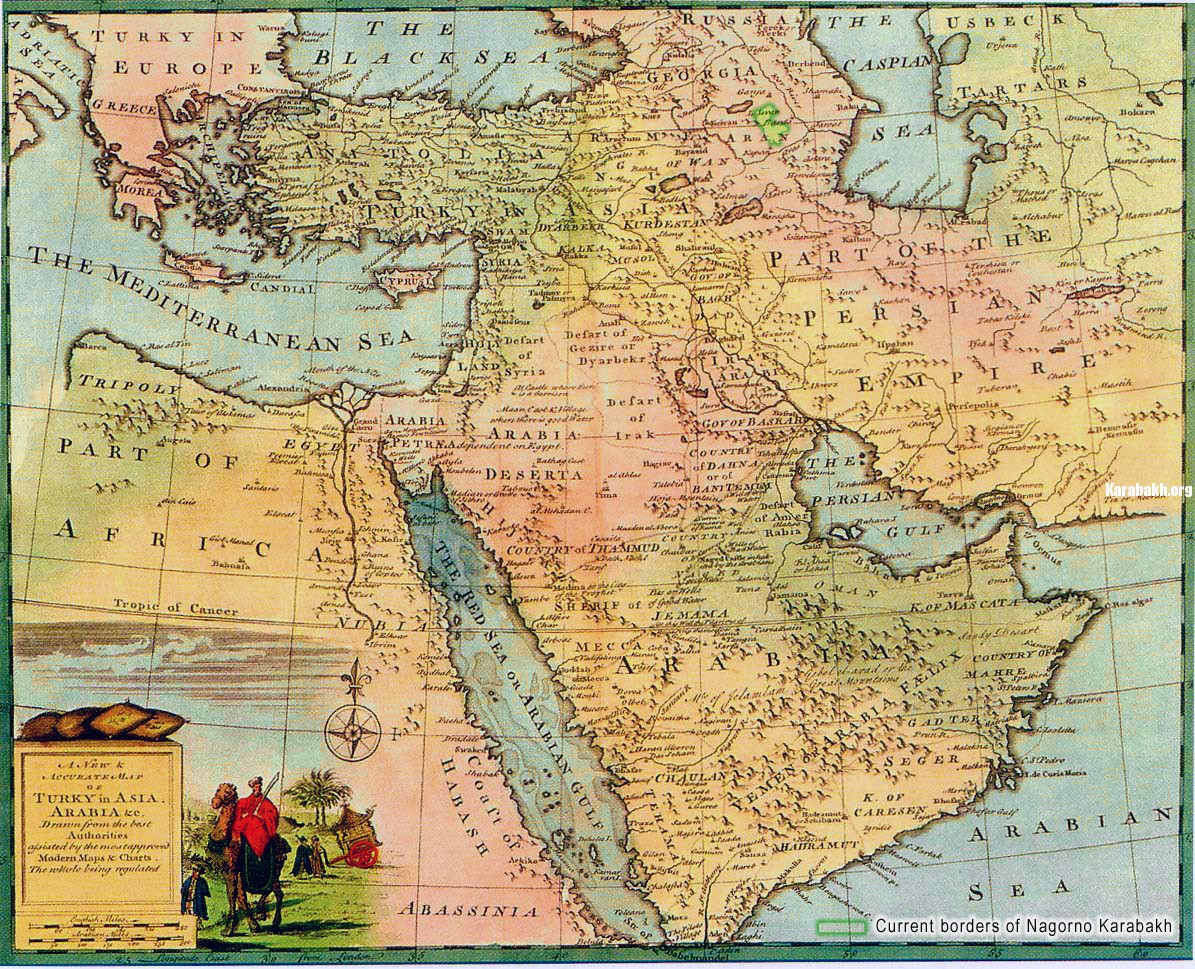

Among the attempts to find an acceptable solution to the NK problem were also regularly proposed schemes which can be provisionally described thus: “More than autonomy, but not a state”. Perhaps the first such scheme was the so-called “Willy’s Plan” which was proposed back in 1919. It envisaged the transformation of NK into a certain “Special Zone” (SZ) in the structure of Azerbaijan under the protection of the USA. (One of the clauses of the project, proposed by colonel of the US Army William Hasckel, read directly: “Security and law and order in the SZ is provided by the Army of the USA under the command of the consul”)10. Now this plan presents only historical interest, except perhaps that it confirms again that the Karabakh problem, despite the claims of many of the nomenclatura statesmen of the Soviet period, is not “invented” but in fact it existed even at that time.

The Aland islands are very often put forward as an example of a conflict resolved without bloodshed and which was solved by finding a special status and limits of self-determination.

The Alands is an archipelago of 8000 islets, situated in the Baltic Sea. The population of these islets spoke Swedish from time immemorial and up till 1808 existed within the structure of the Swedish Kingdom. At that time both Norway and Finland were part of Sweden. As an outcome of the 1808-1809 war Sweden had to give up Finland and the Alands to Russia. After a defeat in the Crimean War in 1856 Russia had to recognize the Alands a de-militarized zone. At the beginning of the 20th century a national referendum was held and Norway peacefully seceded from Sweden. In 1917 Russia recognized the independence of Finland. At this time the Swedish population of the Alands expressed their inclination to re-unite with its ancient motherland Sweden and sent the king of Sweden a petition signed by the entire adult population of the archipelago. In December 1917 Finland came out against the wish of the Allands’ population and suggested that the terms of self-determination should be coordinated with it. The islanders rejected these suggestions. A conflict was growing, however not a single side resorted to arms.

In 1921 the League of Nations passed a resolution: the Aland islands were declared a territory of Finland, neutral and de-militarized. According to the resolution of 1921 Finland was given the responsibility of ensuring the maintenance of the Swedish language, customs and traditions and the development of Swedish culture for the population of the islands.

Sweden and Finland concluded a Treaty according to which the population of the Alands got the right to maintain their language, culture and foundations as a result of which the threat of assimilation vanished. Sweden obtained guarantees about the security of the Swedish population of the islands and the right of unhindered association with them.

According to the Law of 1922 on self-government the local parliament (Lagting) is entitled to adopt laws on the internal affairs of the islands and on the budget. The Lagting appoints the government. In accordance with the Constitution, the laws on self-government can be amended by the Parliament of Finland only with the consent of the Lagting of the Alands. The law-making powers of the Lagting are defined in the following spheres: education and culture; the health service; economy; transport; communal economy; police; post-office; radio and television. In these spheres the Alands have the powers of a sovereign state. All the remaining legal powers are the prerogative of Finland: foreign policy; the major part of the civil code; court and criminal law; customs and money circulation.

To defend the interests of the Aland population one deputy from the archipelago is elected to the Parliament of Finland. With the consent of the Lagting the president of Finland may appoint the governor of the islands. The powers of the governor are to head the Council of the representatives of the islands (which is formed on an equal footing) and to open and close sessions of the Lagting.

Economic relations are set out in the following way: the government of Finland levies taxes, collects customs and other levies on the islands in the way it does across the whole country. The expenses on the archipelago are covered from the state budget. The archipelago gets a proportion of state income after the deduction of part to pay off state debt. It is left to the Lagting to decide how to distribute the rest according to its budget.

The laws adopted by the Lagting are sent to the President of Finland who has the right of veto. This veto can be exercised in two cases: if the Parliament of the islands should exceed their powers or the adopted law represents a threat to the internal and external security of Finland.

The right to live on the islands is equivalent to the right to citizenship. Every child born on the islands has that right on condition that one of its parents is a citizen of the Alands. Alanders are also citizens of Finland. The right of Aland citizenship is granted to any citizen of Finland who has moved to the archipelago and has lived there for five years on condition that they have knowledge of the Swedish language.

Restrictions on the ownership of real estate are accounted for by a wish to secure the lands for Alanders. A resident of an island, who has lived for five years outside the Alands, loses his citizenship. A citizen of the Alands is exempted from the duty of serving in the Finnish Army. It is forbidden to garrison troops and build fortifications on the islands.

The Alanders may directly cooperate with Scandinavian countries. The government of the Alands also takes part in the work of the Council of Ministers of the Scandinavian countries.

Foreign policy is the prerogative of the government of Finland and the Finnish Parliament. But if Finland signs an international treaty that affects the internal affairs of the Alands then the implementation of the treaty should be coordinated with Lagting.

The Aland model was proposed by international intermediaries as a possible future model for relations between NK and the Azerbaijan Republic. On December 21-22, 1993 on the initiative of the ministries of foreign affairs of RF and Finland and the CIS Inter-Parliamentary Assembly a symposium of Azeri, Armenian and NK parliamentarians was held on the Aland islands at which the details of the model were presented. But it was rejected by the authorities of NK as one “which doesn’t take into account the historical foundations and psychological consequences of the Karabakh-Azeri conflict and of the war fought de facto for independence from the Azerbaijan Republic “. Besides, according to the firm conviction of the Armenian side, the Aland model was inapplicable to the conditions of the South Caucasus also for the reason that the question of the status of the archipelago in the 1920s wasn’t a single problem; it was solved in the framework of a general issue, the so-called “Sweden problem” in Finland. Swedes were able to balance their rights not only in the Alands but across Finland as a whole where the Swedish language is the second state language.

It is not the only instance of proposals to settle the problem on the principle of “more autonomy, but not a state”. Many statesmen and experts proposed such ways out as an opportunity for both sides to come out of the conflict with dignity, with minimal losses both to their security and self-respect (which is also important). Let’s take one more example of this kind, presented by American researchers D. Laitin and R.Suny11

- Karabakh de jure must remain in the structure of Azerbaijan in conformity with the principle of territorial integrity of a state and the inadmissibility of unilateral forced changes to borders. The symbolic sovereignty of Azerbaijan over Karabakh could be represented by the Azeri flag, waving over the House of the Government in Karabakh and by the appointment of an Azeri representative in Karabakh, who will have to be approved by the Karabakh government. The formal aspect of sovereignty implies the fact that Azerbaijan will represent Karabakh in the United Nations and other international organizations.

- The citizens of Karabakh must have proportional representation in the Parliament of the Azerbaijan Republic in Baku. The Karabakh representatives in the Parliament of the Republic of Azerbaijan must have the power of stopping any proposed law which directly concerns Karabakh.

- The establishment of full self-government of the Republic of Karabakh within the borders of the Azerbaijan Republic, presupposing the formation of their own Parliament with proportional representation of the population, the right of veto on the resolutions of Azerbaijan concerning this republic, sovereign rights of its government in the matters of security, education, culture and investments in infrastructure.

- The absence of units of armed forces and the police on each other’s territories without mutual consent.

- The Armenians and Azeris living in Karabakh would have the right of dual citizenship or full citizenship in either republic with the right of permanent domicile in Karabakh.

Summing up the above, it should be noted that the variants for settlement of the type “more than autonomy, but not a state”, “associated state” and “common state” often have characteristics interwoven among themselves and are difficult to clearly differentiate.

As far back as in 1988 a group of lawyers, headed by Andrei Sakharov, proposed a variant of “moving apart” Armenians and Azeris as a model for the solution of the conflict. At that time this variant failed to become a subject of discussion.

The first developed plan for such a variant was proposed by an American politologist Paul Goble, who expounded his viewpoint in the article “Coping with Nagorno Karabakh Crisis”. He believes that the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia are unable to solve this problem themselves. And not a single solution is possible, if the sides try to return to the status quo ante, to the situation existing before the start of the current struggle in 198812.

The status quo ante, notes P. Goble, was maintained thanks to the USSR, which no longer exists. Now the situation has changed and it dictates the necessity to find a new approach to the NK conflict.

P. Goble thinks that “in principle there are three ways ‘to solve’ the NK problem: to oust or kill all Armenians living there now, to mobilize a great number of foreign forces to move these sides apart or to keep NKAR (Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Region of Azerbaijan, what was the status of NK during the Soviet Rule) under Armenian control”. But the author himself thinks their realization is impossible: the first option because of moral considerations, the second because it is not physically possible, and the “third is impossible because in this case Azerbaijan will become the side unfairly treated both by losing its territory and in the question of water supply for Baku”. Therefore he sees the key to the solution of the problem in the exchange of territories, including the following terms:

Firstly, handing over part of NK to Armenia together with the areas where rivers flowing in the direction of Azerbaijan rise. Secondly, handing over the Armenian territory between the Azerbaijan Republic and Nakhchivan to Azerbaijan’s control.

Evidently P. Goble understood that in case of realization of this variant Armenia will fall into a difficult situation because it will lose its connection with Iran, vitally important for Armenia. This is why in 1996 he brought in some amendments to his plan. In particular, he proposed to form a corridor across the southern Megri region of Armenia to Iran, where some international forces will be disposed.

Goble suggested later handing a part of NKAR to Armenia in exchange for handing over part of Armenian territory, namely the Megri region, to Azerbaijan. This would enable Azerbaijan to have an immediate border with Nakhchivan.

Goble’s plan, for one reason or another, didn’t enjoy the support of, in the first place, the Republic of Armenia and NK. It is important, however, to note that, according to the information of the media and opposition figures in Armenia, some variant of territorial exchange like the one proposed by Goble was seriously considered during talks between the presidents of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia in 2000-2001. Officially Yerevan and Baku refuted these allegations and there wasn’t any additional information about this variant, even if it was actually discussed. (see further).

Statesmen and political science specialists often pay great attention to the conception of the associated state, as one of the variants of solution for ethno-political conflicts, including the NK conflict. They usually refer to the resolutions and declarations of the United Nations, in particular to resolution № 2625, adopted by the General Assembly of the UN in 1970, the “Declaration on the Principles of International Law Pertaining to Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States”.

The Declaration admits three forms of realization of the right of self-determination: formation of a new state; association with an already existing independent state or status of a different level, provided it is approved by the free will of a given people. In the present case the variant of free association with an independent state is of some interest. This variant is not only a political concept but is already realized in practice. The islands of Cook and Near already have associated statehood with New Zealand, while Puerto Rico, the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia have associated statehood with the USA. The last two – the Republic of the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia — even became members of the United Nations in 1990.

Proceeding from this principle John Maresca, the former special representative of the USA in negotiations on NK, worked out and presented on July 1,1994 a plan for the political solution of the NK-conflict. J.Maresca’s proposition consists of eight chapters in the first of which “The Status of Nagorni Karabakh” it is noted that “NK must be called the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and must be a completely self-governed legal formation within the sovereign state of the Azerbaijan Republic”13 . “NKR must be within Azerbaijan and associated with it”. Maresca proposed to adopt a Main Law about the status of NKR. Its clauses would bring about the associated integration of NKR with the Azerbaijan Republic. It was suggested establishing in Stepanakert and Baku representative offices; NKR could have permanent representatives in capitals of countries of special importance such as Yerevan and Moscow, and receive corresponding representatives from those countries. But “NKR mustn’t be recognized as a sovereign independent state”.

According to Maresca’s plan. “the armed forces of NKR must be gradually scaled down. NKR must be entitled to have local security forces, including self-defence forces, but mustn’t have weapon of an offensive character. And the Azerbaijan Republic gains the right to station in NKR only local security forces but it cannot locate in or near NKR weapons of an offensive character.

There are some clauses in J.Maresca’s variant about the right of the Republic of Armenia to maintain transit links with NKR across the Lachin corridor, and the Azerbaijan Republic with Nakhchivan across the territory of Armenia. There also articles about the return of refugees to the places of their former residence, about making the Republic of Armenia and the Azerbaijan Republic, including NK and Nakhchivan, a zone of free trade, about the calling of a conference of donors for financial support of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia, including NK and Nakhchivan, etc. And finally, Maresca proposes that the OSCE and United Nations Security Council should become guarantors of implementing the terms of this document.

The variant of an associated state, though it stops short of unconditional demands for the submission of NK to the laws and jurisdiction of the Azerbaijan Republic, it nevertheless is based on the principle of non-recognition of the independence of NKR and regards it as a part of the Azerbaijan Republic, retaining NKR’s vertical subordination to Azerbaijan. This, to the Armenian side, absolutely fails to correspond to the internationally acknowledged idea of an “associated state”. In the NK leadership’s opinion, the relations with the Azerbaijan Republic must be founded on the principle of complete equality, ruling out any vertical connections.

Among the varieties of this variant can be included the so-called “synthetic variant”, put forward in the middle of the 1990s by the director of the USA’s National Institute of Democracy, ambassador Nelson Ledski, who described his viewpoint in an interview with the Turkish newspaper “Turkish Daily News” (September 1995). In his opinion, NK must virtually become a part of the Republic of Armenia, although possibly, in some form it must be connected with the Azerbaijan Republic. “There’s no doubt,” N. Ledski says, “that Armenians were a success in this war. And the Azeri side must acknowledge that it lost something.”

It would be pertinent here to recall, that, according to the Azeri side, the constant reference of western analysts to the “military successes” and “results of war” represent a concealed hint that a “military solution” to the Karabakh problem is the only possible one.

N. Ledski thinks that the problem of Nakhchivan from the point of view of its communication with the Azerbaijan Republic presents an essential part of the regulation of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict. Answering a Turkish reporter’s question: “Do you propose an exchange of NK for Nakhchivan?”, Ledski said: “There must be negotiations, which will provide communications between NK and the Republic of Armenia as well as between Nakhchivan and the Azerbaijan Republic”.

Though we aim to dwell on the variant of “Common State”, proposed by the co-chairmen of the Minsk Group in December 1998, it is easy to see that this variant is close enough to the conception of an associated state, and the difference between these two variants is conditional. Below we are going to offer a more complete discussion of this variant.

Let’s round up the analysis of this variant by an assessment of the so-called “psychology of apprehensions” of the sides, defined by the Azeri politician and researcher Niyazi Mehti.

“There’s no doubt that NK has a chance to de facto exist, with the retention of some political symbols, as an independent state, formally remaining in the structure of the Azerbaijan Republic. But Armenians are afraid of such a perspective. Firstly, because, if Azerbaijan’s military-economic strength increases and its international position stabilizes, it could take advantage of its legal right of sovereignty and cancel the de facto independence of NK.”

“The absence of one hundred percent guarantees makes NK afraid of even symbolic attributes of NK belonging to Azerbaijan. The other reason is the dynamics of the demographic and migration processes in the Azerbaijan Republic, capable , in the opinion of Armenians, of leading to a repetition of the Nakhichevan scenario, where Azeris, by weight of numbers, allegedly ousted the Armenian population.”

“Thirdly, the proposed subordination of NK to the jurisdiction of the Republic of Azerbaijan will inevitably face the resistance of Armenians of NK and the Republic of Armenia: official persons state that after those victories the people itself will never allow it”

The stand of the Azeri side is conditioned, firstly, by the firm conviction that Upper and Lower Karabakh make up an inseparable entity with the other parts of the republic. Secondly, by the belief that the systems and principles of international law (inviolability of borders, recognition of the Azerbaijan Republic by the United Nations and other international organizations within its factual borders etc.) support Azerbaijan, and to give up these advantages is preposterous. Thirdly, the Azeri side holds that the perspective for a strengthening of the power of the state and as a consequence the possibility of revenge can’t be ruled out. Fourth, international law is inclined, especially lately, to accept precedents which subsequently become the norm and adopt a permanent character. Thus a “domino” effect comes into play: if Azerbaijan makes one concession, it will be forced into further compromises right up to allowing the secession of NK. One example of this cited by the Azeri side is the admittance of the NK Armenians as a side in the negotiations which, according to the “domino” principle, is a step on the way to recognition of NK’s independence14

The so-called Cyprus variant very often emerges in discussions of the ways to settle the Karabakh conflict and the status of NK.

The gist of the “Cyprus model” consists in the fact that this formation (the Turkish republic of Northern Cyprus) isn’t officially recognized by anybody, but exists and functions de facto. The Cyprus model as applicable to NK means: not to recognize it de jure, but consent to its existence de facto. It means that NK won’t be a part and parcel of the Azerbaijan Republic or Republic of Armenia, won’t be officially recognized as an independent state, won’t be a member of the international community, but will exist and function as an independent state formation.

The Cyprus model, in the opinion of the Armenian side, is a compromise. It may allow the sides to reconcile themselves to the existing state of affairs without hurting the national dignity of any side involved in the conflict. It will relax the situation, create a breathing space and in future will encourage a broader approach to the solution of the problem. On the other hand, it will promote the normalization of relations between the neighbors – the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia.

Such a model, in the opinion of the Azeri side, has already been working for eight years, but has not lived up to anybody’s expectations.

Right after the conclusion in 1996 of the Khasavyurt agreements between the leadership of the Russian Federation and the leadership of Chechnya there appeared one more variant for solution of the NK conflict, called the “Chechen variant”. After a long and bloody war the RF and Chechnya came to an agreement on ceasing the war, establishing peace and freezing discussions on the status of Chechnya for five years. This is the sum and substance of the Chechen model, a particular “mechanism of a delayed political status”. After the Russian-Chechen agreement, different circles in the RF, the Republic of Armenia and the leadership of NK started talking about the possibility of application of this model in relation to the Karabakh problem.

It is necessary to consider this transition period during which the stances of the parties are determined. It is thought that if the question of status is delayed, say, for five years, during this time a new generation of politicians may come onto the stage, and the geo-political situation in the South Caucasus as well as the economy will become more clearly defined (get clearer outlined). Possibly, the sides of the conflict will cease to have an overly-categorical approach to negotiations. Thus, the problem may be broken out of deadlock.

To sum it up, the Chechen variant as applied to the problem of NK rests on three principles:

a. Ensuring maximum security for Karabakh and for the residents of the neighboring territories of the Republic of Armenia and the Azerbaijan Republic.

b. Establishment of transitional period for a minimum of five years during which the question of the political status of NK will be frozen. This will give some time and create more favorable political, geopolitical and economic conditions for the settlement of the Karabakh problem.

c. Emergence during this period of a new generation of politicians, free of the baggage and the mutual enmity of the preceding period, will emerge during this period and will act in a new atmosphere and in a new conditions.

It isn’t so difficult to see the following obvious obstacle: the Chechen variant presumes broad negotiations enlisting “the sides to the conflict”, but this has proved impossible even within the framework of the negotiations already going on between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

One variation of “the Chechen variant” is the Dayton peace treaty (1996) according to which the Serb population of Bosnia and Herzegovina is granted “a delayed right” of self-determination after nine years. The leadership of NK has quickly given a positive assessment to the possibilities of the “Chechen variant”. The then leader of NK R. Kocharian stated on February 27, 1997 in Stepanakert that the “variant of the solution of the Karabakh problem in analogy with the Chechen problem is quite acceptable for Karabakh”. He said that as far back as two years ago the leadership of NK proposed to withdraw from the principles of territorial integrity and self-determination, but this proposal was rejected by the leadership of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan, in its turn, believes that the “Chechen variant” is incompatible with the situation in NK. It argues that there is nowhere for Chechnya to integrate with, while NK has already widely integrated with the Republic of Armenia, and five years more will accomplish this process.

The so-called “principle of anomaly” set out by Niyazi Mehti in his aforementioned article can be presented as a particular variety of the “Chechen variant”. We think it important to consider this variant as an example of how, voluntarily and with the readiness of the parties to the conflict, it is possible to get around stumbling blocks and strive to become used to peaceful co-existence while all the time gradually arriving at mutually acceptable legal solutions. Here are the main clauses of this principle.

- The Azerbaijan Republic, the Republic of Armenia and the two communities of NK agree that the region of the conflict is an inter-Azeri anomaly, which can be settled using exceptional, unconventional methods. After acceptance of this thesis the sides appeal to the international community with a call to regard this situation outside the jurisdiction of international principles, which run counter to the status quo. Furthermore, through a number of mutual agreements the situation is brought to a stalemate situation.

- The Azerbaijan Republic recognizes NK as NKR, as a way of recognizing its independence. However, NKR is deprived of the possibility of changing its name or seceding from the structure of the Azerbaijan Republic without approval in an all-Azerbaijan referendum (It is possible that the Azeri side could mark “NKR” in its official documents in inverted comas).

- NKR formally has its own army, but this structure is checked by the inspection of the Azerbaijan Republic and in actual fact becomes a police force deprived of heavy arms. This symbolic army must consist of local Azeris and Armenians. The proportions of Azeris and Armenians must correspond to their proportion in the population of NK.

- NK has a Parliament to which Azeris are elected according to a quota corresponding to the size of the Azeri minority. The Parliament adopts a Constitution on the basis of agreements with the Azeri side within the framework of the basic principles of the Constitution of the Azerbaijan Republic.

- Every 5 years the Azeri Parliament puts forward a question of abolishing NKR. But the deputies of NKR have a right of veto in this case. As soon as this question is brought to discussion the deputies of NKR, proceeding from an official document, presented by the NKR Parliament (to rule out any pressure on the deputies or their being compromised by corruption), submit their veto. The deputies of NKR can exercise their right of veto only in connection with this question. (A number of other symbolic questions can be added here).

- Likewise every five years the NKR Parliament puts forward the question of seceding from the Azerbaijan Republic (creation of their own currency and so on.) and the Azeri deputies proceeding from the resolution of the Azeri Parliament submit their veto. This strange procedure, by the way, must be compulsory because such symbolic procedures remove any psychological tension. In times to come all this will assume the character of a peculiar ritual, like some procedures in the political life of monarchic Great Britain. The therapeutic, psychological effect of this procedure on the Armenian-Azeri conflict can be modeled and studied. The number of such symbolic anomalies in world practice is rather great. For example, the Queen of England is nominal monarch of the whole Commonwealth, but in actual fact she has no political influence in most of the member countries.

- If the Republic of Armenia declares war on the Azerbaijan Republic or any other country NKR is prevented from automatically entering an alliance with the Republic of Armenia as an independent formation by a veto imposed by the Azeri representatives of the Parliament. Similarly, the Azerbaijan Republic if it declares war on the Republic of Armenia, has no right to draw NKR into this war due to the veto of the Armenian side.

It is important to note here that such “rules of the play” don’t hurt the ambition and dignity of the sides and most of the problems are confined to the symbolic arena of confrontation, in which the procedures of the stalemate situation simulate the solution of delicate problems, so removing tension. Naturally, all the names, examples and symbols used in the model are conditional and are only presented to explain the general principles. After consultation the sides can modify some theses of the special autonomy and stalemate situations. In the present situation of confrontation , symbolism has obtained such an acute character that solution of the conflict must also be associated with symbolic procedures15.

For a number of reasons the efforts of international intermediaries in settling the Karabakh problem reached a deadlock and their activities were resumed only in 1998, when the co-chairmen of the OSCE’s Minsk Group came out with a new initiative based on the so-called “common state”.

It was, in fact, an attempt to find an “unconventional” solution, which could as much as possible formally combine the main demands: Azerbaijan’s about its territorial integrity, and NK’s demands for self-determination. The most important items of this variant published in the media are the following (not in the order presented in the official Minsk Group document):

- NK is a state and a territorial formation and together with the Azerbaijan Republic make up a single state in its internationally recognized borders.

- The NK Constitution and laws are effective on the territory of NK. The laws …of the Azerbaijan Republic are effective on the territory of NK if they don’t run counter to the Constitution and the laws of the latter.

- NK will be entitled to have direct external relations with foreign states in the spheres of economics, trade, science, education , culture.

- NK will have a National Guard and police forces… They can’t act outside the NK borders.

- The army, security forces and the police of the Azerbaijan Republic won’t have a right to enter the territory of NK without the consent of the NK authorities.

However, it seems overall that this conception was not fully defined. This is evident from the fact that there was no consensus on a name for the conception. In fact, besides the name “common state” it has also been variously described as the “single,” “joint” and even “union” state conception.

It is obvious that there is an essential difference between “single”, “common” and “allied” states. In the first case – the “single state” – a unitarian form of state is meant, within the framework of which there may or may not be limited or “broad” autonomy. And if namely this was offered to the conflicting sides in 1998 by the co-chairmen of the OSCE’s Minsk Group, then it should be admitted, that there was no novelty in their offer. But in the second case – the “joint state” – two forms of state configuration are being described at once: federation and confederation. Judging by the words of the then Russian representative Yuri Yukalov, the Armenians of NKR were in fact invited to agree to become a member of some kind of federation, while it is not clear what sort of amorphous status the Minsk Group co-chairman offered NK as part of this hypothetical federation.

But as far as “union state” is concerned, this clearly describes a federation, which can be symmetric or asymmetric and its subjects may exist on an equal or unequal legal basis.

As to the sum and substance of proposals about a “common state” it should be noted that the matter concerns the conception of federalism in the countries of the South Caucasus, which Russia adhered to in its intermediary mission up until 1995 and only then gave it up because of the Azerbaijan Republic’s and Georgia’s positions. Besides, at the stage of regulation of the NK conflict we are describing, this idea was already put forward in a vague way by the USA. A study of the text of proposals of the co-chairmen of the Minsk Group from the period November-December 1997 gives us grounds to think that the chief idea of RF – and of the USA and France which joined Russia in this question — was an intention to expand the ordinary notions about interrelations between a “federal center” and a “subject of the federation”. For instance, it was presumed that NK, while returning to the legal sovereignty of Azerbaijan, would nonetheless maintain all external attributes of independent statehood: the institute of the presidency, Parliament, government, Constitution, court system, army (in the form of a National Guard) the police, a state emblem, national anthem, flag and so on. But as to NK maintaining its communication links with the outside world the following was offered: the Azerbaijan Republic “rents out” to the OSCE the zone of the Lachin humanitarian corridor and the OSCE establishes its control over it “in collaboration and interaction” with the leadership of NK and using manpower provided by official Stepanakert working jointly with observers from the OSCE. NK is deprived of the possibility of carrying out an independent foreign policy and having independent banking and finance spheres. But at the same time this territory was declared to be a free economic zone with unlimited use of any foreign currency.

These and other articles of the peace proposals of the Minsk Group co-chairmen enable us to conclude that, though the terminology speaks of preserving Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity as a single state, the thrust of the international intermediaries proposals was to set a course towards the formation of a union of states between Azerbaijan and NKR, that is to say a confederation and an asymmetric one at that.

At the present moment NK and the Republic of Armenia stated that they are ready to accept these proposals of the Minsk Group as a basis for negotiations. Meanwhile Azerbaijan, referring to the norms of international law and its national interests, rejected this proposal.

The conception that the future of the South Caucasus countries lies in their integration, up to the level of political integration at that, isn’t new (It is sufficient here to recall the term “the Caucasian Benelux” coined by Eduard Shevardnadze as far back as the first half of the 90s). But a group of researchers from the Center of Researches of European politics in Brussels headed by Michael Emerson proposed a very radical variant of such a development of events, presuming that integration in itself may turn out to be a key to the solution of both the Karabakh and the other conflicts of this region. This proposal assumes the following elements:

– Readiness of the leaders of the three recognized states of the South Caucasus to immediately take steps towards regional integration; creation of the so-called South Caucasus community.

– Consent of the EC, Russia and the USA to sponsor such integration.

– Readiness to realize a plan (“agenda”) of six items, three of which pertain immediately to the South Caucasus, three, to collaboration in a wider region, including the Black sea zone and the South of Russia. The first three items include: “Constitutional resolutions for international conflicts, in particular, with the use of modern European models of shared sovereignty as well as inter-dependence of different levels. It is proposed for the most important conflicts – Nagorni Karabakh and Abkhazia, to make provisions for a high degree of self-government, exclusive competence, separate Constitutions, horizontal and asymmetric relations with state powers and joint competence in such spheres as security, foreign relations and economy. Special articles must be drafted on peace-making and guarantees of security for refugees.

The project also stipulated the possibility of the federalization of Georgia and Azerbaijan proceeding from their cultural-ethnic characteristics so as to avert conflicts in the regions where national minorities reside. All this was to be followed by concrete measures on formation of the South Caucasus community, presuming compact political and economic integration of all states of the region. It also presupposed an active participation of other organs such as the OSCE, as well as the RF,EC and the USA in this project16.

The project, as was to be expected, failed to bring any concrete results due to the failure to find any interest among the leaders of the states of the region.

Here we can mention the analogous model of Emil Agayev17 which he called “Trans-Caucasian Confederation” or “South-Caucasian Union”(SU). According to this conception, his union could include not only at first two and then three independent states, which after entering confederate relations will retain their sovereignty. On definite terms (stipulated in each separate case) autonomous entities could also be included as associate members. Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Ajaria, Nagorni Karabakh (plus – Nakhchivan), would in this case remain subjects of the sovereign republics but granted the right to participate on an equal basis in confederate life as a whole. Each of them would get the right to live as it wishes but within a certain framework without interfering with the others. All this is determined by a Treaty about the formation of the Confederation. This Treaty must also stipulate that all territorial and other claims must be consigned to the past for once and for all. But then it will be easier to settle many disputed questions. It will be easier to return refugees to their native places. The main point is that it is easier to settle these difficult problems.

The formation and functioning of the South Caucasus Union, according to Agayev, could be realized with the help and even through the mediation of the world community, otherwise it would be difficult to achieve.

The possibility of the formation of such a confederation could be considered in the context of global tendencies towards integration. The question is: whether the time for the formation of an integrated (common) political space has come and how to organize the process of controlled, “predictable” globalization , leaving space for the development of peoples and their cultures.

The empires which have now almost disappeared into history has one advantage: on their vast territories there really was a dialogue of cultures, a meeting of civilizations and interaction of peoples. It is ridiculous now, in the 21st century, to turn back to the political past, but proposals for the formation of a new type of confederation of countries, encompassing one region, is a subject worthy of consideration. The South Caucasus and the territories that border it – Russia, Turkey, Iran, the Caspian countries of central Asia, some Black sea countries – are geographically and economically predisposed to integration. All the pluses and minuses of such a step, in our opinion, are worthy of critical analysis.

In essence, one more sub-variant of a solution through integration is the model proposed in 1996-98 by the leftist forces of the Republic of Armenia and NK, supported by the communists of the RF. According to this scheme, settlement of the conflict could be achieved through joining the internationally recognized and non-recognized states of the South Caucasus to the Byelorus-Russian Union (now – the Union state) as single formations. In 1997, more than 1 million signatures in the Republic of Armenia were collected in favor of this decision, as the leaders of Communist Party of Armenia and of the public organization “Armenian people’s initiative Russia-Byelorus-Armenia” (APIRBA, held this campaign), claimed. According to some data, the leadership of NK were also predisposed to this idea. However the official rulers of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia (and Georgia likewise) showed a negative attitude to it.

We have to consider the initiatives covered by this title separately not because of any intrinsic merit but because they have been circulating for more than a year. What the gist of these “principles” is the participants of the negotiations have not made known and it is possible in fact that they coincide with some variants described earlier. After the meeting on April 4 -7, 2001 in Key West, Florida, the initiatives also were commonly described as the “Key West” principles.

It is of some interest to note that the President of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev, who had previously affirmed, that there weren’t any “Paris initiatives”, stated in June 2002 that these principles were nothing but a proposal about an exchange of corridors between the sides i.e. Megri and Lachin. Armenia’s President Robert Kocharian denied these statements, but refused to disclose the details of these principles.

After the meeting in Key West publications appeared in the media of Azerbaijan and Armenia about the variant of “Andorra status” (condominium) which had allegedly been proposed. This foresaw having “plenipotentiary representatives” of Azerbaijan and Armenia participating in the power structures of NK. It also spoke of other “attributes” including the establishment of some kind of international control over the “corridors”.

It is possible this was just a trial balloon to gauge the prevailing opinions in Azerbaijan , Armenia and NK. In reality the co-chairmen of the Minsk Group could hardly have intended either to propose such a plan to the sides in the conflict or to consider the plan themselves. The issue is that any “Andorrized” variant of settlement, logically, must be based on a denial of the right of “new Andorrans” to maintain their own armed forces. As it became clear from the public statements of the Minsk Group co-chairmen in Stepanakert and Yerevan and especially N. Gribkov and P. de Suremain, the international community is apt to understand, that NK long ago turned into a “big independent factor” of inter-Caucasian politics. Evidently that means that the co-chairmen of the Minsk Group are inclined to give the armed forces of NK a distinct role within that factor. And in the case of “Andorrization” of NK or a similar settlement, the USA, RF and France would have faced the difficult task of fully and unconditionally disarming the army of NK and demilitarizing the territories of not only NK but also of the regions bordering it within Armenia and Azerbaijan. It is natural that in Azerbaijan the co-chairmen should pronounce quite different statements, acknowledging the mandate of negotiations exclusively between the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia, the scope of which can be expanded after achieving the first favorable results.

1 We’ll mention, by the way, that parts of a State, the population of which does not differ from the rest by nationality often strive for self-determination (or, as it is often said, display separatism). Even during the last decade the movements to separate from a given State were registered in Italy, Indonesia, Canada, Mexico and USA, where in some cases even no predominance of any ethnic group is registered.

2 M. Halperin, D. Sheffer. Self-determination in the New World Order. Washington D. C. 1996, p. 46

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

5 Materials of the seminar: “The process of peaceful regulation of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict”. Tsakhkadzor, 23-25 July, 2001

6 Lukhterhantd. O. Nagorno Karabakh’s Right to Independence According to International Law. Boston, 1993

7 Ibid

8 See, in this connection the statements of outstanding foreign specialists Kh. Khannum, M. Eizner, G. Espinel and others, quoted in the article by E. Kurbanov: Ethnic-political conflicts in Trans-Caucasus: their sources and ways of solution, p.58,59,60 and others

9 See. Information of Noyan Tapan agency, 25 April 2002

10 We express our gratitude to political analyst R. Musabekov who kindly provided us a text of the project

11 David D. Laitin and Robert Grigor Suny. Armenia and Azerbaijan: Thinking a way out of Karabakh. Middle East Policy. Volume VII; Number 1 October 1999

12 Goble P. Coping with Nagorno Karabakh Crisis. The Fletchers Forum of World Affairs,v.V1, N 2, Summer1992

13 United State Institute of Peace. War in the Caucasus. A Proposal (by John Maresca) for Settlement of the Conflict over Nagorno Karabakh, Washington D.C., 1994, p.5

14 We express gratitude to Professor N. Mehti for providing his unpublished article

15 Niyazi Mehti, the mentioned article

16 See details on the cite: www. ceps. be

17 We thank the author for lending us his unpublished article.