While Western attention is turned to the atrocities taking place in Syria, the massacre of Khojaly and its significance for Europe today seems to be forgotten, writes the European Azerbaijan Society in Brussels (TEAS).

“At a time when major news channels and newspapers in the West are filled with images and stories of violence and suffering of people in the Syrian town of Homs, it is tempting to dismiss events which occurred decades ago and to question the wisdom of reviving old memories and scratching old wounds. What happened 20 years ago in the Azerbaijani town of Khojaly, however, matters. It mattered then, and it still matters now.

On 26 February 1992, 613 civilians, including old men, women and children, were massacred in one of late 20th century’s most brutal and horrific attacks. Despite its horrendous nature, the crimes committed were largely ignored by Western governments and the Western media at the time.

But despite sparse international news coverage immediately following the Khojaly massacre, Western media outlets quickly turned their attentions to other major conflict zones of the era, such as the Balkans and then Rwanda. So whereas the massacres and ethnic cleansing which occurred in those regions became very well known the West, the vast majority of the world’s population knows nothing about Khojaly, or about the Azerbaijani–Armenian conflict which continues to this day.

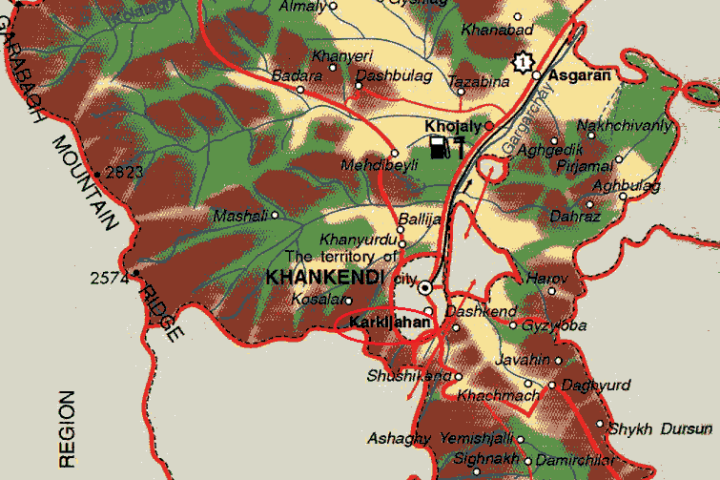

The Khojaly massacre occurred during the armed conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, a region inside Azerbaijan with a substantial ethnic Armenian population. After capturing most of the region and expelling ethnic Azeri inhabitants, Armenian forces, with the assistance of the Soviet Army’s 366th motorised regiment, which was stationed in the regional capital of Khankendi (Stepanakert), carried out a veritable bloodbath among the Azerbaijani population in the town of Khojaly. The town had been besieged by the Armenian units for four months before the actual assault. At the time of the storming several thousand inhabitants still remained, many of whom were the sick, injured, old, women and children – all those who had been unable to flee before the siege.

The rare reports, photos and footage taken by Western journalists, such as Anatol Lieven (The Times) and Thomas Goltz (Washington Post) at the scene of the massacre, shed light on this war crime. Those killed were subjected to atrocities unimaginable in a civilised society. Among those slaughtered were 116 women and 83 children.

The massacre in Khojaly was nothing less than criminal ethnic cleansing, a precursor of other similar crimes. These criminal acts were undertaken with the aim of frightening the Azerbaijanis – not just the military but also civilians – into losing the will to resist, thereby facilitating further victories. The lawyers of the international organisation Human Rights Watch have classified the tragedy in Khojaly as a “massacre”, and the bloodbath among the civilian population as a war crime.

The Khojaly massacre matters because those civilians were in the process of fleeing their homes when they were killed. They had been warned of the consequence of staying, and they had been offered a safe corridor out, and they had reluctantly decided to leave. However, that promised safe passage turned into the killing fields of Khojaly.

It also matters because of the manner of the deaths of those 613. They were shelled, and shot, and battered – and butchered even after death, as many graphic images testify. The fact that this was the biggest death toll in any one day of the conflict is obviously important, but it was the hideous nature of the attacks which made Khojaly the symbol of the more than thirty thousand people, on both sides, who died between 1988 and 1994. And, of course, it is vital to remember that they are still dying on the line of contact to this day.

And the Khojaly massacre matters most of all because the man who proudly boasted about the ‘strategic’ significance of this brutal attack is now a head of state. As reported by the British scholar and writer, Thomas de Waal in his acclaimed book Black Garden on the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the current Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan, who was at the time one of the commanders of the ethnic Armenian forces, said: “Before Khojaly, the Azerbaijanis thought that they were joking with us, they thought that the Armenians were people who could not raise their hand against the civilian population. We were able to break that [stereotype]. And that’s what happened.”

Of course all such incidents and tragedies have to be put in context. At the time the Soviet Union was breaking up, and the peripheral regions of that once mighty empire were in turmoil. The eyes of the world were fixed on the former Yugoslavia, where hundreds of thousands of civilians were being ethnically cleansed – evicted, brutalised and killed. The difference, of course, is that the perpetrators of those crimes in the former Yugoslavia are now in prison, not in power.

The European Union has had its problems in recent years. The economic downturn has exposed flaws in the single currency, and caused political tensions within and between the member states. But these difficulties are transient, and will be solved as economies revive. The main benefit of the EU – its raison d’etre some would say – is that it has brought peace and democracy to states that in the not too distant past were at war or suffered under dictatorships.

Despite the difficulties and distractions which the EU currently faces, it should not ignore conflicts and injustices amongst its near neighbours. Caucasian states are members of the EU’s Eastern Partnership, they need and deserve support.

The OSCE Minsk Group peace process has been under way for 18 years, and has achieved little or no progress. The EU needs to engage in the peace process, and bring its considerable economic, diplomatic and moral muscle to bear. The South Caucasus serves as the crossroads between east and west. The outbreak of outright hostilities between Azerbaijan and Armenia would add to the turmoil of what is already an unstable region in Europe’s backyard.

The United Nations intervened when the original conflict broke out. The UN Security Council passed four resolutions calling on Armenia to stop the killings and to withdraw from sovereign Azerbaijani territory. Those resolutions were ignored at the time, and remain unimplemented to this day. As a result, there are more refugees and internally displaced persons in Azerbaijan than anywhere else in Europe or on Europe’s borders.

So that is why the Khojaly massacre matters, and why its killing fields should not be forgotten. These tragic events may have occurred 20 years ago, but the survivors still mourn, and the refugees and internally displaced still long to return to their homes. Twenty years of talk and tension are too much. The deadlock must be broken, and the EU – along with the UN and the OSCE – can play a vital role in ensuring that there are no more Khojaly’s and no more massacres.”

The European Azerbaijan Society is an organisation promoting Azerbaijan to international audiences and creates a sense of community for expatriate Azerbaijanis.