International media have a long history of presenting political events in terms of their religious context.

Reports on the recent Egyptian elections, for example, cast the election results as an “Islamist win”; political commentary was shaped by the parties’ religious backgrounds. Similar tendencies were seen in the Caucasus during the 1990s, where ethnic conflicts were portrayed as religious divisions.

Recently, a meeting of the presidium of the Inter-Religious Council of the Commonwealth Independent States was held in Yerevan, Armenia, on Nov. 29-30. Catholicos Garegin II (head of the Armenian Apostolic Church), Sheikh ul-Islam Allahshukur Pashazade (Chairman of the Caucasus Muslims Department) and Russian Patriarch Kirill II all attended the presidium meeting in Yerevan, and held a trilateral meeting.

Some international observers were surprised that Pashazade visited Yerevan, especially given that there were debates in both Azerbaijan and Armenia about what the meeting would offer on the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. After the meeting, Garegin II sent a letter to Pashazade in which he emphasized the importance of discussions between regional religious leaders with regard to resolving key regional issues, including the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Pashazade proposed during the meeting that the spiritual leaders should also meet at the front line between the Azerbaijan and Armenian armies, a proposal that was accepted by the Armenian church.

Over the past year and a half, there appears to have been renewed interest in engaging Armenia and Azerbaijan’s religious leaders in the peace process, even if only on a symbolic level. On April 26, 2010, Catholicos of All Armenians Garegin II attended a meeting of world religious leaders in Azerbaijan upon the invitation of Azerbaijani Shiite leader Sheikh al-Islam Pashazade. During his visit, Catholicos Garegin II met with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and went to pray in an abandoned Armenian church in Baku. Garegin II’s visit to the Armenian Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator in central Baku also raised an important direction of potential collaboration and mutually beneficial confidence-building measures: the joint preservation of cultural monuments and heritage.

During my recent conversation with Onnik Krikorian, an Armenian journalist, he suggested that this inter-religious dialogue has the potential to ease bilateral relations, especially if it receives greater publicity. “Pashazade’s visit to Yerevan is of course important and will hopefully result in more high-level exchanges, or even discussion between civil society activists and journalists. But few people in Armenia seemed to know about the visit, and even then, the wife of a major opposition figure I spoke with who did [know], didn’t know that the Catholicos had visited Baku and conducted a service in the Armenian church in April of last year. Nonetheless, the two visits at least serve to underscore that the Karabakh conflict is not a religious dispute.”

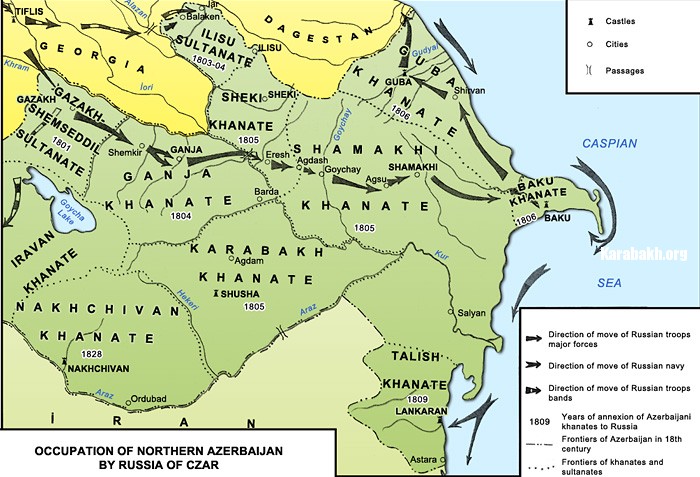

The Caucasus region is extremely diverse in terms of both religion and ethnicity, a true mosaic of cultures. Perceptions of this diversity have suffered as a consequence of misleading and reductive commentary in the Western media. During the 1990s, Western reporters often framed the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as “the conflict between Christian Armenians and Muslim Azerbaijanis.” As a result, theorists such as Samuel Huntington have happily used the Caucasus, and especially Nagorno-Karabakh, to demonstrate the concept of “fault lines” between “civilizations,” where the risk of violent clashes is greater. There is a tendency to assume that when there are religious differences, these differences must be at the heart of the conflict, but such an explanation is often incomplete. In the case of the Karabakh conflict, it is misplaced and misleading. While it is the case that the Catholicos of all Armenians, Vazgen I, wrote to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in February 1988, asking him to accept the demands of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians, and even went on Armenian television to speak about his request, it is also true that spiritual leaders were never at the forefront of the respective movements and their behavior was driven more by desire for peace. In 1994, Vazgen I, Pashazade and the Russian Orthodox Church jointly encouraged the Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders to work together for peace.

It is interesting, then, that following the signing of a cease-fire agreement in 1994, religious discourse has not played a bigger role in conflict resolution. During the war, Armenia destroyed many of Azerbaijan’s unique cultural, historical and religious sites. The Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) — now known as the Organization of Islamic Cooperation — has on several occasions raised the importance of the Azerbaijani history, culture, archaeology and ethnography that is located in the territories occupied by Armenia, naming these sites and artifacts an integral part of Islamic heritage, and noting the damage wrought upon the Islamic heritage in the occupied territories. Azerbaijan is currently supporting inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue and cooperation between various nations, the World Forum on Intercultural Dialogue, for example, as well as the restoration of the Udi Church, with the aim of preserving the rich cultural heritage of the South Caucasus.

Given the emotional intensity of this deeply entrenched conflict, there will be many who urge caution in heralding these meetings as signs of a new, more positive phase in the negotiating process. These types of interactions are valuable for Track 2 diplomacy (non-state actors), though ultimately they are subordinate to Track 1 (state actors). Azerbaijani society in general recognizes the importance of Track 2 diplomacy, but there are more than 1 million displaced persons from the occupied territories who need to see political developments. Rather than seeing greater civil society interaction as a potential catalyst for confidence building, given the massive highs and lows of expectation and disappointment brought by the Minsk Group negotiations, Armenia seems to be taking a hard line, ignoring civil society initiatives.

Officials from the Azerbaijani Community of Nagorno-Karabakh region recently tried to meet with Karabakh Armenians, but the meeting was never held. At the same time, deaths at the front line have risen. For both sides, increased contact at community levels will create a pool of experience informing each side’s choices in the peace process, and can contribute to Track 1 diplomacy. First, Armenia must recognize that Nagorno-Karabakh has two communities, Azerbaijanis and Armenians. Second, pursuing Track 2 diplomacy could increase confidence building measures, and demonstrate that political will can be supported by other conflict resolution methods. Finally, the Armenian government must understand that the prolongation of the status quo will help no one – on the contrary, it will amplify the mistrust between the parties to the conflict.