[toc]

ABSTRACT

The author draws on the documents, published and unpublished, of the Moscow and Kars conferences to discuss Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

By Way of Introduction1

On 5 May, 1920, at its first meeting, the government formed two days earlier by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (TBMM) decided that instead of waiting for Moscow to answer the letter Mustafa Kemal had dispatched on 26 April, it would start official negotiations with the government of the R.S.F.S.R. The delegation consisted of Foreign Minister Bekir-Sami Kunduh-bek and Minister of Economics Yusuf Kemal Tengirshek-bek; later they were joined by Osman-bek from Lazistan, who knew Russian.2

Meanwhile, on 5 and 6 May, Kâzim Karabekir Pasha, who commanded the Eastern Army, sent Mustafa Kemal two telegrams from Erzurum to express his concern about the delay: “The Armenians are agitated; there is information that they too dispatched a delegation to seek collusion with the Bolsheviks. We should act immediately; every day missed could bring great losses.”3

The Talks Begin (July-August 1920)

On 11 May, 1920, the Turkish delegation left Ankara; in Erzurum it acquired two more members, Dr. Ibrahim Tali (Öngeren) and Seyfi-bek (Dusgeren), military experts recommended by Karabekir Pasha.4

Since the foreign minister refused to travel by sea, the delegation moved toward Maka (via Bayazid and Nakhchivan); it turned out, however, that the land route was unsafe. The delegates had to return to set out once more on 11 July, 1920. This time they traveled by sea and arrived in Moscow on 19 July.5

Several Turkish officials, however, arrived much earlier: Halil Pasha and Dr. Fuad Sabit-bek arrived on 16 May; Enver Pasha and Ittihad members Jamal Pasha, Dr. Bahattin Şakir, and Badri-bek came from Germany on 27 May; late in May Tegmen Ibrahim-bek delivered Kemal’s letter of 26 April.

The Ittihad group headed by Halil Pasha had already spoken to the Soviet officials and even reached an agreement on financial and military aid.

On 3 June, Ibrahim-bek returned to Anatolia with a letter from Georgi Chicherin.6

The talks began on 13 August; the Turks who had arrived on 19 July, 1920 were unofficially received by Deputy People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the R.S.F.S.R. Lev Karakhan twice on 24 July. Soviet Russia was biding for time: it needed to sort out its relations with Armenia.

On 19 July, People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Chicherin informed Erivan that Anatolia had begun mobilization and that peace involving all the sides was Armenia’s only chance. Soviet Russia, in turn, pledged to join the peace treaty.

On 31 July, 1920, Boris Legran, who represented Soviet Russia in the Caucasus, met A. Jamalyan and A. Babalyan, who represented the Dashnak government, in Tbilisi7; on 10 August the Russian-Armenian treaty was signed, which left Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan under temporary Soviet administration. The Gumri-Shakhtakhtli-Julfa railway could be used by Armenia (not for military purposes).8 Russia promised to negotiate territorial concessions with the Turks.

The official talks between Soviet Russia and Turkey began on 13 August in Moscow. People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Chicherin tried to dispel the Turks’ concern over the Russian-Armenian treaty, which they heard about on 13 August, the day the talks began. The Soviet official claimed that the transfer of Van and Bitlis to Armenia would promote Turkish interests in the future. He added that Halil Pasha and Jamal Pasha had already agreed.9

The Turks retorted that by acting in this way Russia was no better than any other colonialist state and that Halil Pasha and Jamal Pasha had not been empowered to talk on behalf of Turkey.10

The first day was wasted because of Georgi Chicherin’s unacceptable claims.

The next day, the delegation met with Lenin, who confirmed that signing the treaty with the Armenians had been a necessity dictated by the circumstances, but went on to admit that “it was a mistake we will try to correct. If we fail to do so, you will have to correct it.”11 The leader of Soviet Russia assured the Turks that Sovietization of Armenia and Georgia in the near future would settle all the problems.12

On 17 August, the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs appointed A. Sabanin and E. Adamov to discuss the basic principles of a treaty with Turkey. The preliminary stage, between 17 and 24 August, produced a draft of eight articles, but Chicherin’s position on transfer of the Anatolian lands to the Armenians proved to be a stumbling block. The talks were suspended.

Having secured financial and military aid, the Turkish delegation returned to Anatolia.13

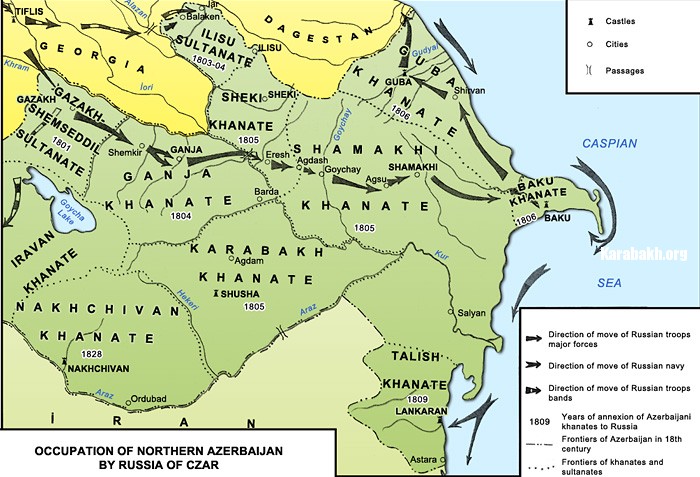

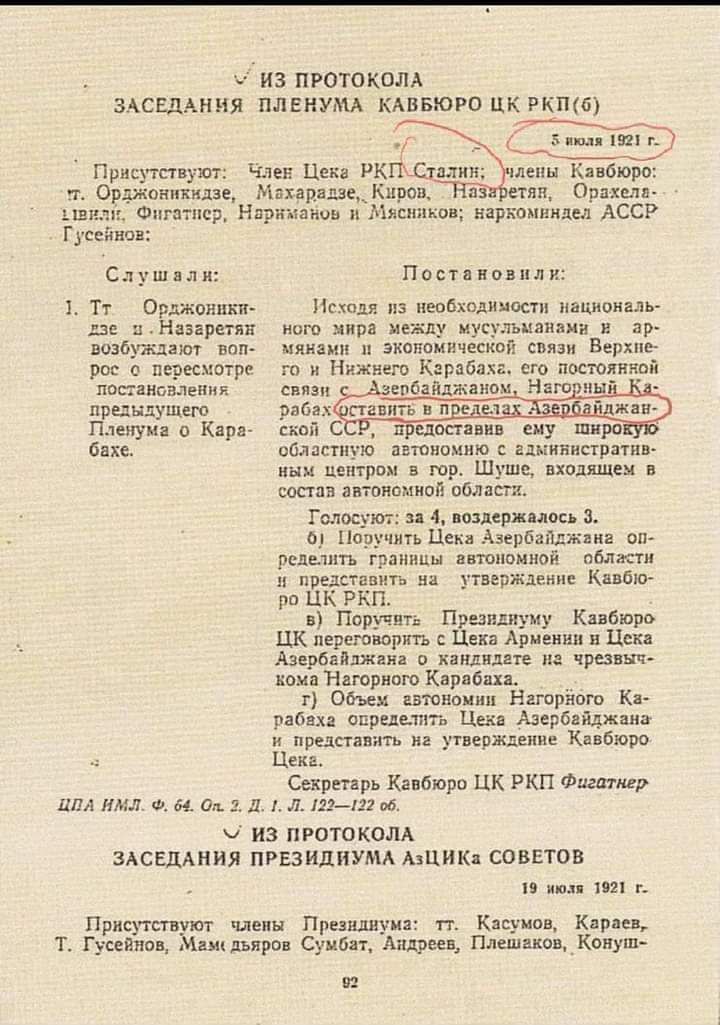

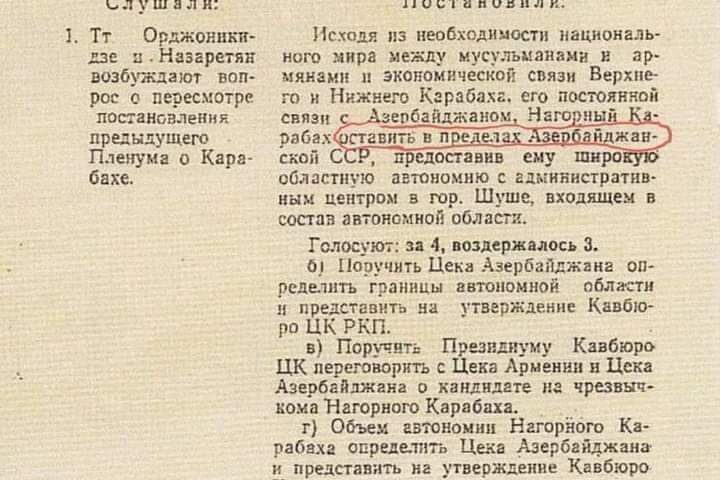

Territorial Integrity of Azerbaijan at the Moscow Conference

In the fall of 1920, Turkey launched military action against Armenia; in December 1920, the sides signed the Gumri (Alexandropol) Treaty. Russia was worried.

On the other hand, Moscow knew that Turkey could find new allies in the West: the land transfer issue had to be dropped. Polikarp Mdivani, who represented Russia, explained that the “land transfer issue was raised by mistake,” because of misinterpreted collisions.14 In a note sent to Ankara, Georgi Chicherin refrained from using the tern “Turkish Armenia;” he merely confirmed Moscow’s intention to continue the talks and sign a treaty.15

On 22 December, 1920, the TBMM government informed Moscow by telegram that it approved the Soviet suggestions and supplied a list of Turkish delegates.16

The Turks suggested Baku as a venue; Chicherin, who said that the leaders of the R.S.F.S.R. could not leave for Baku, insisted on Moscow as the place for the talks and promised stable communication with Ankara via Armenia and Novorossiysk.17

The failed first stage of the Moscow talks caused a lot of worry in Ankara: Turkey badly needed a treaty with Russia and stable relations with it. To speed up the process, Ali Fuat Cebesoy was appointed Ambassador to Russia on 21 November, 1920.18

On 14 December, the Turkish delegation left Ankara.19 It included Minister of Economics Yusuf Kemal, delegation head, Minister of Education Riza Nur, and military representative Saffet (Arykan)-bek.20 On 7 January, 1921, they reached Kars; on 15 January (after some delay), they joined Cebesoy and his embassy (Cebesoy had arrived in Kars on 16 December). On 18 February, the Turkish delegation reached Moscow.

The same day, the Turks met Chicherin and Karakhan for unofficial talks; passions flew high. On 22 February, the Turks turned to Stalin for support21 and were encouraged: the prospects looked brighter than before.

The official talks began four days later, on 26 February. Soviet Russia was represented by Georgi Chicherin and Jelal Korkmasov (the Turks insisted that Armenian Karakhan be excluded).

When opening the conference, under the rotating chairmanship of Chicherin and Kemal, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs said that they had gathered together in order to sign a treaty of friendship, the main provisions of which had been agreed upon the previous year.22

Another Turkish delegation headed by Bekir Sami-bek was talking to the British in London. According to the European press, British Premier Lloyd George promised Turkey the Transcaucasus, along with the oilfields of Baku, if Turkey moved against Soviet Russia.23

In Moscow, Chicherin, who referred to the London talks as “anti-Soviet,” wanted to know: “Does Sami-bek in London represent Ankara or Istanbul?”24

The London talks produced no positive results; the British leaks to the press were intended to undermine the Moscow talks.

The Russian side insisted that Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia be represented: the Kremlin wanted to have a firm grip on the foreign policy of the Transcaucasian republics in order to set them against Turkey. The Turks declined the suggestion on the grounds that they were not empowered to talk to them.

On 26 February, 1921, Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Azerbaijan in Moscow Behboud Shakhtakhtinsky telegraphed the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. M. Huseynov: “…The Turks do not want Azerbaijan and Armenia at the conference. They argue that they have no contradictions with Azerbaijan and that they will sign another treaty with it. They do not want the Armenians because they consider the Gumri Treaty valid and have no intention of denouncing it. Russia, on the other hand, is dead set against a treaty with us (Turkey.—V.G.) and wants an Azeri and then an Armenian representative at the conference. I am against Azerbaijan’s involvement for the simple reason that I have nothing to say there. We should not quarrel with the Turks over trifles. I enjoy a certain amount of clout with them; there are all sorts of combinations to be realized in Anatolia. If I go against the Turks at the conference on issues unrelated to Azerbaijan, I might lose a lot. Russia is talking about friendship and brotherhood, not an alliance.”25

In fact, the most controversial issues which cropped up in Moscow were related to Azerbaijan (with the exception of the Batumi question): the Nakhchivan question and the Independence of Azerbaijan.

The Turks attached great importance to the former because at that time Nakhchivan was playing an important role in the contacts between Azerbaijan and Turkey and was an intermediary between Moscow and Ankara (Nakhchivan was involved in many other strategic and geopolitical issues). Turkey acquired Nakhchivan under the Treaty of Batum of 4 June, 1918 and regarded it as its property.

On 13 December, before the delegation set off for Moscow, its head Yusuf Kemal asked Mustafa Kemal: “What should I do if the Russians insist on retrieving Nakhchivan?” The answer was: “Nakhchivan is the gate to Turkey. Bear this in mind and don’t spare efforts.”26

On 10, 12, and 14 March, 1921 in Moscow, the talks on the Nakhchivan question became fierce: the Turks wanted to remain in control, while the Russians were resolutely against this.

The Turks turned to Stalin once more; Behboud Shakhtakhtinsky was also present. When Stalin asked his opinion, the Azeri envoy answered: “Nakhchivan should remain an independent state under Russia’s protectorate.”27

On 10 March, 1921, the Turkish delegates put their trump card on the table. They argued that since the population of the contested area had invited Turkish troops, this meant that it was under the protectorate of Turkey.28 The Gumri Treaty spoke of the same.29 The Russian side refused to accept this argument.

The Turks suggested that Nakhchivan remain an independent state under the joint protectorate of Turkey and Azerbaijan30; Russia, likewise, refused to accept this.

There was another attempt to achieve a consensus: Turkey was prepared to transfer protectorate to Azerbaijan on the condition that it pledged not to transfer it to third states.31

The Russian side agreed to discuss Nakhchivan autonomy under the protectorate of Azerbaijan and its borders with certain reservations:

First, they refused to regard Turkey’s suggestion as a concession because the Treaty of Alexandropol had been never adopted, which meant that the invitation the population had extended to the Turkish armed forces had no legal power and could not, therefore, be regarded as a foundation for protectorate.

Second, since Azerbaijan was unofficially involved in the talks, it could not assume responsibilities of any sort.

Finally, the Russian formula, “consistent contacts between the Nakhchivan Region and Azerbaijan and autonomy under the protectorate of Azerbaijan,” was supplemented with the Turkish reservation, “Azerbaijan should not transfer protectorate to any third state;” delimitation of borders of the Nakhchivan Magal was entrusted to military experts.32

On 12 March, the talks on the border between the Nakhchivan area and Armenia developed into fierce debates. The Russians insisted that since at no time had Azerbaijan been a patron of any part of the Erivan Uezd, the border, as drawn by experts, went beyond all reasonable limits.

It was said that the Soviet republics were closely interconnected and that, therefore, the border issue was of secondary importance; the borders of the Sharur-Daralagyaz District should be based on the ethnic principle.

The Turkish position was the opposite; the Turks argued that:

(a) the bloodshed which made introduction of Turkish troops inevitable started in Nakhchivan;

(b) the majority of the area’s local population was Muslim, therefore Azerbaijan should become the patron of the contested territory.33

In disregard of the Turks’ firm stand, the Russians were determined to transfer control over Nakhchivan to Armenia some time in the future.

They believed that the border between Nakhchivan and Armenia would be drawn on the strength of direct talks between the two states and any territorial concessions made before that would not be regarded as violations of Azeri protectorate.

The Turkish diplomats, who proceeded from Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity and security of the eastern borders of their own state, insisted on an immediate decision; they excluded the possibility of future talks with Armenia.

The talks went on for a long time, until finally it was decided, on Turkey’s suggestion, to transfer the Sharur-Daralagyaz District to Nakhchivan and draw the border along the Kemurlu Dagh (6930)34 and Saray-Bulak (8071) mountains in the contested part of the Erivan Uezd (the new border began at Ararat Station); these questions were referred to the mixed conciliatory commission consisting of representatives of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey.35

On 14 March, 1921, the conference finally agreed on the status of Nakhchivan.36

This meant that the Turkish diplomats managed to save part of Nakhchivan for Azerbaijan (with the provision that it would not be transferred to third states).

On 18 March, 1921, Russia and Turkey signed the Treaty on Friendship and Brotherhood; the Turkish side wanted the date changed to 16 March (the anniversary of the occupation of Istanbul).

The Russians agreed, since the Turk’s proposal went along with Russia’s desire to normalize relations with Britain (this was the day the two countries had signed a trade agreement).

The date of the Treaty of Moscow was changed from 18 to 16 March on the sides’ mutual consent.37

The document was signed by Chicherin and Korkmasov on the Russian side and by Yusuf Kemal, Nur, and Cebesoy on the Turkish.38

Art III of the Treaty of Moscow (which consisted of 16 articles and 3 Annexes), which was related to the Nakhchivan issue, said: “The contracting sides agree that the Nakhchivan Region within the borders specified by Annex I (B) to the present treaty becomes an autonomous territory under the protection of Azerbaijan, providing that it not be transferred to any third state.

“A commission composed of delegates of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia will readjust the border of the Nakhchivan territory as being wedged between the Arax talveg in the east and the line of Mt. Dagna (3829), Veli Dagh (4121), Mt. Bgarsik (6587), and Mt. Kemurlu Dagh (6930) in the west, starting at Mt. Kemurlu Dagh (6930) and crossing the Saray-Bulak mountain (8071) to Ararat Station. It will end at the convergence of the Kara-Su and the Arax.”39

Appendix I (B) to the Treaty described the Nakhchivan borders in the following way: “The Ararat Station, Mt. Saray-Bulak (8071), Mt. Kemurlu Dagh (6839 or 6930); from there to the elevations of 3080, Sayat Dagh (7868), the village of Kurt Kulag (Kyurt Kulak), Mt. Gamessur Dagh (8160), the elevation of 8022, Kuki Dagh (10282), and the eastern administrative border of the former district of Nakhchivan.”40

Turkey and Russia guaranteed that the Government of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. would not transfer Nakhchivan to Armenia.

Upon his return to Ankara, Yusuf Kemal said to Mustafa Kemal: “Esteemed Pasha! We did our best on the Nakhchivan issue;” to which Mustafa Kemal answered: “Yusuf Kemal-bek! Our gates protect us, this is most important.”41

On 16 April, 1921, the Turkish troops left Nakhchivan; on 20 July, the R.S.F.S.R. Central Executive Committee (CEC) ratified the Treaty of Moscow; the next day the Grand National Assembly of Turkey did the same. On 22 September, the sides exchanged ratification instruments in Kars.42

Attempt to Sign a Turkish-Azeri Treaty

In Moscow, the sides discussed the attempt of the TMBB government to sign a treaty with Azerbaijan. True to the principles of “socialist centralism,” Russia did not want Turkey to sign treaties with the Transcaucasian republics; the Turks hoped at least to preserve the independence of Sovietized Azerbaijan.

The Turkish diplomats forced the Russian side to accept the possibility of a treaty between Azerbaijan (as a sovereign republic) and Turkey. Later, however, Russia made this absolutely impossible.

The Turkish side, which wanted a separate treaty with Azerbaijan, objected to its involvement in the Moscow talks; the Turks intended to show Russia that they treated Azerbaijan as a sovereign state.

The Turkish draft contained the following points:

1. Pooling the efforts of the two states to liberate the East and fight imperialism;

2. In the event of a treaty between Turkey and Entente, the former pledged to dispatch armed units to Azerbaijan, which pledged to finance the emissaries.

3. Azerbaijan pledged to support the national-liberation struggle in the East, but a Soviet government could be set up in Azerbaijan if the nation wanted it.

4. Azerbaijan could not enter treaties with Entente without Turkey’s approval.

5. Turkey pledged to help Azerbaijan in the event of an Entente attack.

6. Azerbaijan pledged to supply Turkey with oil and oil products while it was involved in revolutionary activities in the East.

On 1 April, 1921, the Turkish delegation left Moscow for Baku, taking 4 million gold rubles supplied by the Soviet government with it. When it reached Baku on 8 April, it tried to persuade the government of Azerbaijan S.S.R. to sign a separate treaty. The Azeri leaders, who were no more than Moscow puppets, refused to sign the treaty.43 On 9 April, 1921, Georgi Chicherin warned the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. Huseynov not to engage in any talks with the Turkish delegation; the same telegram invited the Azeri representatives to come to Tiflis to present a united front, together with Armenia, to the Turks at a general conference to be held in the city.44

Chicherin sent the draft of a treaty to Tiflis that the Transcaucasian Soviet Republics were to sign with Turkey; he deemed it necessary to warn that the Turks would try to engage Baku, Erivan, and Tiflis in separate talks and instructed the three republics to be prepared to act together in Tiflis.45

No separate treaty was signed: the allegedly independent Soviet government of Azerbaijan went along with Moscow on the issue of a “single treaty between the Transcaucasian republics and Turkey.”

On 19 April, 1921, the Turkish delegation met Mirza Huseynov and Commissar of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate Behboud Shakhtakhtinsky for the last time; it was agreed to hold a joint conference of the Transcaucasian republics and Turkey in Kars.46

On 19 April, 1921, the day the Turkish delegation left Baku, Mirza Huseynov informed Chicherin of the following: “Shakhtakhtinsky and I spoke to the Turks and insisted on a joint conference of the Transcaucasian republics and Turkey. Although displeased, the Turks agreed, on the condition that each of the republics sign the treaty individually. We announced that we accepted this. The Turks wanted Kars as the venue; if the other republics (Armenia and Georgia) agree, Azerbaijan will not object.”47

The Kars Conference

Azerbaijan wanted Baku or Tiflis as the venue of the conference; the Turks wanted Kars.48

Azerbaijan and Turkey agreed on Kars49: on 3 July, 1921, however, Yusuf Kemal informed Mirza Huseynov by telegram that his new duties as Foreign Minister of the TBMM government did not allow him to go to Kars. He suggested Ankara50; the Soviet side declined this.51

It should be said that Envoy Plenipotentiary of the R.S.F.S.R. in the Transcaucasus Boris Legran was worried about even the small amount of independence Azerbaijan had displayed. In his telegram of 22 June, 1921 addressed to M. Huseynov and N. Narimanov, he wrote: “You should not act on your own. You should discuss everything with the republics. I insist that in the future you should not act without informing the envoy plenipotentiary of the R.S.F.S.R.”52

After exchanging diplomatic correspondence, Ankara, Baku, Moscow, Tiflis, and Erivan53fixed the place (Kars) and date of the future conference: 26 September, 1921.

On 22 September, 1921, in Kars, the Turkish and Russian delegations exchanged the ratification instruments of the Treaty of Moscow of 16 March, 1921.54

The conference was opened on 26 September, 1921 at 19.00. Commissar of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate Behboud Shakhtakhtinsky represented Azerbaijan; Georgia was represented by Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs Shalva Eliava and Commissar for Foreign Affairs and Finances Alexander Svanidze; Armenia, by Commissar for Foreign Affairs Askanas Mravyan and Commissar for Internal Affairs Poghos Makinisyan. Yakov Ganetsky, Envoy Plenipotentiary of the R.S.F.S.R. to Latvia, acted as an intermediary.55

According to Kâzim Karabekir Pasha, the Bolshevik delegation numbered 150 members (officials and auxiliary staff).56

The Turkish delegation was headed by Kâzim Karabekir Pasha, TBMM member and Commander of the Eastern Front; it also included TBMM Burdur deputy Veli-bek, M. Shevket-bek, who represented Turkey in Azerbaijan, and Mukhtar-bek, chief engineer of the railway construction project in Eastern Anatolia.57

On 17 September, 1921, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the TBMM government Yusuf Kemal sent the Turkish representatives his “briefing” with respect to entering the treaties with each of the Transcaucasian republics.

The draft treaty with Azerbaijan envisaged the following:

(1) The treaty should be written in clear terms in Turkish58; its Preamble should contain statements that confirm the brotherhood between both nations.

(2) Their relations with other states should proceed from both Azerbaijan and Turkey rejecting all treaties and international acts imposed on them by force.

(3) The Azeri side should pledge not to transfer its patronate over Nakhchivan to any other state.

(4) The treaty should contain an article relating to the Turkish emigrants in Azerbaijan and the Azeri emigrants in Turkey (the Turkish government should acquire the right to grant Turkish citizenship to any Azeri emigrants who ask for it).

(5) Turkey should receive a share of the profits from the Baku oilfields.

(6) Education in Azerbaijan should be free (to preserve national schools to prevent Russification).

(7) The article related to Batum (in the treaty with Georgia) should not appear in the treaty with Azerbaijan, or the article related to Nakhchivan in the treaty with Georgia, etc.59

It should be said that in Kars the delegations of the Transcaucasian republics and Soviet Russia acted as representatives of a single state.

On the whole, the atmosphere was tense; the sides could not arrive at a common decision about the treaty (a single treaty or separate treaties with each republic). The Turks insisted on separate treaties, while Russia and the “independent states” could not accept this.

The talks reached boiling point when Karabekir Pasha refuted everything Ganetsky had to say with weighty arguments and continued insisting on separate treaties.60

On 30 September, at the fourth sitting, Kâzim Karabekir Pasha suggested that the treaty consist of two parts: one of them should deal with the relations with all the Transcaucasian, republics, while the other should envisage the trade and border issues with each of the republics separately. This, too, was rejected.61

Behboud Shakhtakhtinsky ended the debates by saying that the Transcaucasian republics had been de facto united economically, politically, and militarily and that a single treaty suited their interests and those of Turkey from the point of view of political expediency.

He concluded his contribution with: “In the name of the Azerbaijan Republic, I suggest that the treaty be united with no separate sections dealing with the republics.”62 This settled the issue: the Turks agreed on a single treaty.63

In Kars, the Turkish and Soviet sides voiced their suggestions.

The Turks regarded most of what the Soviet side wanted (permission for Georgia to carry out archeological digs in Eastern Anatolia; transfer of the salt industry in Kulp and the ruins of Ani to Armenia; permission for Armenia to use of the railway via Gumri; aid to the starving population of Erivan, etc.) to be interference in their domestic affairs and rejected it. Some of the proposals (supplies of railway equipment and foodstuffs to Armenia) were accepted.64

The Turks, in turn, tried to settle certain problems: they wanted Turkish citizens to be returned their requisitioned commodities and receive immunity for their personal belongings; Turkey also wanted a share of the profits from the Baku oil fields and the right to use the Batum port.

It should be said that the treaty afforded Turkey access to the port of Batum, but nothing was said about a share in oil profits. Shakhtakhtinsky declared that Turkey would receive aid, but Azerbaijan was not ready to shoulder any official responsibilities.65

The Kars conference paid special attention to the Nakhchivan issue; the Turkish delegation supplied its draft based on the Treaty of Moscow.

The memorandum the Transcaucasian republics submitted to the Turkish government suggested that “an autonomous Nakhchivan Soviet Republic within the Azerbaijan Republic with slightly changed borders in favor of Armenia” be discussed along with other issues.

Even before the conference, the Azeri and Armenian diplomats met in Tiflis where they reached an agreement on the issue. In Kars, they merely tried to clothe their agreement in legal garbs.

The Turkish delegates were informed that the Nakhchivan issue could be resolved without Ankara, while a mixed commission (with Turkish representatives) would be unwelcome in the Transcaucasus.

On 13 October, 1921, the long discussions and debates between Turkey, on the one side, and Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia (with Russia in the background), on the other, was crowned with the Treaty of Kars, which consisted of 20 articles and three Annexes. The text, with few exceptions, was identical to the Treaty of Moscow of 16 March, 1921.66

Art V of the Treaty of Kars said: “The Turkish Government and the Soviet Governments of Armenia and Azerbaijan are agreed that the region of Nakhchivan, within the limits specified by Annex III to the present Treaty, constitutes an autonomous territory under the protection of Azerbaijan.”67

Art V did not comprise the provision of the Treaty of Moscow which said that Azerbaijan should never transfer the right of protectorate to third states.

Annex III “Territory of Nakhchivan” said: “The village of Ourmia, from there by straight line to Azerdaian Station (leaving it to the SSRA), then by straight line to Mt. Dash-Burun west (3142), the watershed of Mt. Dash-Burun east (4108), crosses the river Kyahaanam-Darassi to the south of the inscription ‘Rodne’ (Boulakh) (South), follows the watershed of Mt. Bgarsik (6607) or (6587), and from there passes along the administrative border of the former districts of Erivan and Sharur, Daralagyaz, through the elevation of 6629 to Mt. Kemurlu Dagh (6839 or 6930); from there to the elevations of 3080, Sayat Dagh (7868), the village of Kurt Kulag (Kyurt Kulak), Mt. Gamessur Dagh (8160), the elevation of 8022, Kuki Dagh (10282), and the eastern administrative border of the former district of Nakhchivan.”

Russia’s political ambitions made ratification a long process: the Transcaucasian republics (instigated by Russia) insisted that the treaty signed by Turkey, on the one side, and the Azerbaijan S.S.R., Armenian S.S.R., and Georgian S.S.R., on the other, be ratified in the name of a union of Transcaucasian states (which did not exist at that time).

Turkey stood its ground, which led to Soviet Russia suffering defeat: on 17 March, 1922, the TMBB ratified the Treaty of Kars.

On 3 March, 1922, the CEC of Azerbaijan ratified the Treaty, to be followed by Armenia (20 March) and Georgia (14 June). The ratification instruments were exchanged on 11 September, 1922 in Erivan; the Treaty came into force on the same day.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

Under the Treaty of Kars, which had no expiry date, Armenia recognized Nakhchivan as part of the territory of Azerbaijan.

The Third Congress of the Party Organizations of the Nakhchivan Area held on 23 February, 1923 described Nakhchivan joining the Azerbaijan S.S.R. as an important prerequisite for the region’s economic, political, and cultural progress.

Four days later, the Third All-Nakhchivan Congress of the Soviets, which opened on 27 February, 1923, discussed the question of the Nakhchivan S.S.R. joining Azerbaijan as an autonomous republic. The Congress adopted a Declaration which recognized the necessity of Nakhchivan joining Azerbaijan as its inalienable part.

On 8 January, 1924, the Transcaucasian CEC, after discussing the earlier decision of the CEC of Azerbaijan, ruled that the Nakhchivan area “should be declared the autonomous Nakhchivan S.S.R. within the Azerbaijan S.S.R.”

On 9 February, 1924, the CEC of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. issued a decree which transformed the autonomous area of Nakhchivan into the Nakhchivan A.S.S.R. with its own legislative and executive structures; the autonomy was administrative, not political.

1 The context and pre-history of the events described in this article are given in the work by V. Gafarov, “Russian-Turkish Rapprochement and Azerbaijan’s Independence (1919-1921),” The Caucasus & Globalization, Vol. 4, Issue 1-2, 2010, which also contains more detailed information about some persons mentioned in the present publication.—Ed. Back to text

2 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, Guarding the Motherland, Bahar Publishers, Istanbul, 1967, pp. 145-146 (in Turkish).Back to text

3 K. Karabekir, Our War for Independence, Vol. II, Yapy kredi Publishers, Istanbul, pp. 786-790 (In Turkish). Back to text

4 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., p. 148. Back to text

5 See: Ibid., p. 151. Back to text

6 See: S. Yerasimos, Turkish-Soviet Relations. From the October Coup to “National Resistance,” Gezlem Publishers, Istanbul, 1979, pp. 152-155 (in Turkish). Back to text

7 See: Ibid., p. 166. Back to text

8 The Archives of the Defense Ministry of the Turkish Republic (ATASE), A. 1/4282, K. 588, D. 118-36, F. 6-3.Back to text

9 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., p. 167. Back to text

10 See: Ibid., pp. 167-168. Back to text

11 TBMM, Protocols of Secret Meetings, Vol. I, Part II, Ankara, 1985, p. 166 (in Turkish). Back to text

12 See: A.F. Cebesoy, Moscow Reminiscences (21/11/1921-2/6/1922), Vatan Publishers, Istanbul, 1955, pp. 72-73 (in Turkish). Back to text

13 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., pp. 178-181. Back to text

14 I.E. Atnur, Nakhchivan: From the Ottoman to Soviet Rule (1918-1921), TTK Publishers, Ankara, 2001, p. 438 (in Turkish). Back to text

15 See: Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. III, Gospolitizdat, Moscow, 1959, pp. 391-392. Back to text

16 See: Ibid., p. 436. Back to text

17 See: Ibid., pp. 391-392. Back to text

18 See: A.F. Cebesoy, op. cit., pp. 100-101. Back to text

19 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., pp. 198-199. Back to text

20 See: Ibid., p. 199. Back to text

21 See: S. Sonyel, The War of Turkish Liberation and Foreign Policies, Vol. II, Turkish Historical Society, Ankara, 1986, pp. 52-53 (in Turkish). Back to text

22 See: Ibid., p. 54. Back to text

23 See: Istoria vneshney politiki SSSR., 1917-1985, in two volumes, Vol. 1, 1917-1945, Nauka Publishers, Moscow, 1986, p. 144. Back to text

24 Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. III, pp. 589-590. Back to text

25 Archives of Political Documents at the Administration of the President of the Azerbaijan republic (APD UDP AR), rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheet 2. Back to text

26 M. Kemal, “Nakhchivan, the Gates of Turkey,” Collection on the History of the Turkish Peace, No. 64, April 1992, pp. 5-6 (in Turkish). Back to text

27 Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., p. 222; K. Karabekir, op. cit., p. 1062. Back to text

28 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 41-46. Back to text

29 See: State Archives of the Azerbaijan Republic (GAAR), rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 55, sheet 86. Back to text

30 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., p. 222. Back to text

31 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 41-46. Back to text

32 See: I. Musaev, Politicheskoe polozhenie v azerbaidzhanskikh regionakh Nakhchivan i Zangezur i politika zarubezhnykh gosudarstv (1917-1921), Baku University Press, Baku, 1996, pp. 302-303. Back to text

33 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 48-54. Back to text

34 The numbers under which the points appeared on the map. Back to text

35 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 41-46. Back to text

36 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheet 59. Back to text

37 See: Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., p. 230. Back to text

38 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 66, sheets 19-22; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 67, sheets 1-4; APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 93-95; Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. III, pp. 597-604; Yu.K. Tengirshek, op. cit., pp. 293-299. Back to text

39 GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 58, sheets 143, 146; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 66, p. 19a; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 67, p. 1a; APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 93-94; Archives of the Ottoman Government (BOA), HR. SYS, D. 2309, G. 1. Back to text

40 GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 66, p. 22; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 67, p. 4. Back to text

41 M. Kemal, op. cit., p. 6. Back to text

42 See: Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. III, p. 604; K. Karabekir, op. cit., p. 1110. Back to text

43 See: TBMM, Protocols of Secret Meetings, p. 231. Back to text

44 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 15, p. 139. Back to text

45 See: Ibidem. Back to text

46 See: Ibid., sheet 227. Back to text

47 APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheet 199. Back to text

48 See: APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheet 199; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 2, f. 27, sheet 163. Back to text

49 See: TBMM, Protocols of Secret Meetings, p. 229. Back to text

50 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 49, sheet 8; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 66, sheet 28. Back to text

51 See: Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. IV, Gospolitizdat, Moscow, 1960, pp. 227-228. Back to text

52 APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheet 47. Back to text

53 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 49, sheets 7-8; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 66, sheet 29; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 133, sheets 13, 19-22, 30, 32; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 27, sheet 163; APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheet 199. Back to text

54 See: Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. III, p. 604; K. Karabekir, op. cit. Back to text

55 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 81, sheets 136-141; APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 1, inv. 10, f. 16, sheet 84. Back to text

56 See: K. Karabekir, op. cit. p. 1112. Back to text

57 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 81, sheets 136-141; K. Karabekir, op. cit., p. 1111. Back to text

58 It was recommended to use French, the diplomatic language of the time, in the treaties with the other Transcaucasian republics, to avoid misunderstandings. Back to text

59 See: K. Karabekir, op. cit., pp. 1112-1116. Back to text

60 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 81, sheet 5; K. Karabekir, op. cit., pp. 1125-1126. Back to text

61 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 81, sheet 21. Back to text

62 GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 81, sheet 30. Back to text

63 See: Ibidem. Back to text

64 See: K. Karabekir, op. cit., pp. 1119-1120, 1121-1122. Back to text

65 See: K. Karabekir, op. cit., p. 1120. Back to text

66 See: GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 5, sheets 136-141; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 69, sheets 9-19; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 123, sheets 122-125; APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 110-115; Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. IV, pp. 420-429; K. Karabekir, op. cit., pp. 1128-1132. Back to text

67 GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 5, sheets 136-141; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 69, sheets 9-19; GAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 123, sheets 122-125; APD UDP AR, rec. gr. 609, inv. 1, f. 94, sheets 110-115; Dokumenty vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol. IV, pp. 420-429; K. Karabekir, op. cit., pp. 1128-1132. Back to text