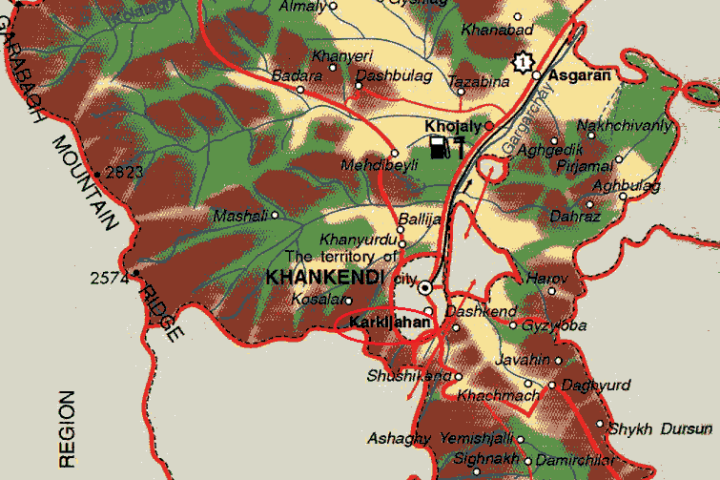

In the context of the problem of the correlation between the two principles Armenian experts note one circumstance, which they think to be very important and has to do with the problem of NK. The thing is that the leaders of Armenia, including its current President Robert Kocharian also speak in favor of the principle of the inviolability of state borders and underline that the self-determination of Nagorno Karabakh does not run counter to the principle of the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan because NK has never been a part of the independent Azerbaijan Republic – either in 1918-1920 or after the break-up of the USSR (NK declared independence in September 1991, three months before the USSR’s demise). Moreover, the fact that Azerbaijan, having accepted the Declaration of the Supreme Soviet (Council) on the Restoration of the State Independence of the Azerbaijan Republic (on August 30, 1991) and the Constitutional Act On the State Independence of October 18, 1991, has proclaimed itself the successor of the Azerbaijan Republic of 1918-1920, (and has declared the annexation of Azerbaijan by the Red Army illegal) is, in the opinion of Armenian experts, is a basis for legally proving the presence of NK separate from AR.9The Azeri side regards this approach as a free interpretation of both the real historical events and international principles, pointing out that the international community invariably acknowledges that NK is part of the Azerbaijan Republic. Moreover, contrary to the opinion of the Armenian party, still in September, 1919 Azerbaijani Democratic Republic and the congress of Armenians of Nagorno Karabakh concluded a temporal agreement on the belonging of this territory to Azerbaijan up to the decision of the international conference. During the Soviet period, congresses of the Armenian population of NK defined the determination to create an autonomous region within Azerbaijan. According to the laws of the USSR, the establishment of an autonomy of a region was initiated by the Supreme Soviet of a union republic upon the presentation of the Soviet of People’s Deputies of an autonomous region, and the aspiration of the Armenian party “not to notice” the legal capacity of these representations can lead to refusal (de jure and de facto) to recognize the legitimacy of the creation and existence of the autonomous region during the Soviet period.

The Azeri side considers the Karabakh conflict exclusively from the perspective of Armenia’s territorial claims and, therefore, insists that this question has no contradictions in the context of international law or clash with other principles. The conflict must be considered exclusively within the framework of the international principle of the integrity of the state within the borders recognized by the international community when the Azerbaijan Republic was admitted to the United Nations: namely, within the administrative borders of the union republic (the former Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic). As to the frequently debated problem of self-determination, it is noted that in all international documents there are clauses which completely remove its priorities. Thus, all international documents on self-determination contain a clause according to which“nothing in this document can be interpreted as violation of the territorial integrity of a state”. On the other hand, it is said that“at present the world community recognizes only the internal aspect of self-determination – the right of the existing states to restore their independence if they are occupied or conquered by foreign forces”10.

Azerbaijan also refuses to discuss the grounds for NK’s secession from the Azerbaijan Republic, which are presented and declared by the Armenian side as “legitimate”. Azerbaijan doesn’t recognize the so-called referendum on independence held in NK in December, 1991, stating that it was held without the participation of the Azeri population and in conditions that formed as a result of ethnic cleansings of the region. After the events of November 20, when the helicopter with leading members of Azerbaijan’s government and representatives of the presidents of Russia and Kazakhstan was brought down, the parliament of Azerbaijan abolished the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Region on November 26, 1991. It was in that period that the population of the region, under the influence of the aggravating conflict often turning into acts of confrontation and armed clashes, segregated by ethnic principle and territorial enclaves, which excluded any negotiations on “the referendum on independence” in December, 1991.

The Azerbaijan Republic notes that the opposite side persistently covers up the fact that during numerous conventions and meetings in 1923 and in following years, the Armenian population repeatedly spoke in favor of establishing an autonomous region within Azerbaijan, motivating it by the geo-economic interdependence of Mountainous (Nagorno) and Lowland Karabakh11.

The Azeri side states that if the main thing, a territorial difference between Azerbaijan and Armenia, is eliminated, the existing problems of the future status of NK must be solved between its two ethnic groups.

The Azeri side mentions that today not a single state in the world – and the Republic of Armenia is not an exception – has dared to recognize NK’s independence at the state level, whereas the territorial integrity of the Azerbaijan Republic is recognized by all international documents. After the statement of Presidents Bush and Putin in 2002 about the search of peace within the framework of the territorial integrity of the countries involved in ethno-political conflicts, the Azeri position obtained new support.

The last year was marked by a new wave of discussions about the problem of Nagorno Karabakh at prestigious international forums. Within the framework of the winter session of the PACE (on January 25, 2005) in Strasbourg, the report of British MP David Atkinson on the question of Nagorno Karabakh, which initially had been prepared by its first rapporteur Terry Davis, who is now the Secretary General of the Council of Europe, was heard. This document for the first time admits that “significant parts of the territory of Azerbaijan continue to remain occupied by Armenian forces, and separatist forces are still in control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region.” Besides, the CE Parliamentary Assembly confirmed that “the seizure of the region from a state and its sovereignty can be achieved only as a result of a peaceful and legal process based on democratic support of the residents of a given territory, but not by way of an armed confrontation leading to ethnic resettlements and a de facto annexation of this territory by another state.” A resolution on the report was adopted.

The Parliamentary Assembly of the OSCE, for whose session (Washington, July 2005) the report of special representative of the PA of the OSCE on NK Göran Lennmarker had been prepared, became another similar forum. The report, which, as one could expect, should have become a basis for the discussion and adoption of the resolution, additionally contained the following provisions:

– Armenian central concern is national security, Azerbaijani central concern is of injustice caused by the occupation of a part of the country and refugees and internal immigrants. It is vital that the parties should satisfy the central concern of the opposite party.

– It is necessary that a certain bi-partisan “truth and reconciliation committee” should try to reach a common and objective understanding of the past.

– There is a golden opportunity for Armenia and Azerbaijan to build mutual relations based on European standards on the support of European structures.

– Armenia and Azerbaijan could strive to build, together with Georgia, a common area characterized by security, democracy, and prosperity.

It is stated in the report that granting independence to NK would be a bad precedent for the South Caucasus where there are a lot of territories trying to achieve independence, though NK could receive the greatest degree of security as part of Armenia. As to the alternative, in the form of a high-degree autonomy within Azerbaijan, in the opinion of the speaker, this variant could be realized under the scheme of the Aland Islands (see below). In any case, in Lennmarker’s opinion, the first step should be the establishment of direct contacts between Azerbaijan and NK.

No resolution was adopted on the Lennmarker report in view of the negative attitude to it of the Azerbaijan delegation. Both the PACE resolution and the Lennmarker report are included in the Appendices of this book.

In the light of all stated above, the viewpoint of a number of experts, who believe the legal approach to finding a solution to the problem of NK is a dead end, seems important. In particular, they point out that international law contains a lot of different principles that can often come into clash. Speaking at the conference “Formation of the Environment for Peace, Stability and Trust in the South Caucasus” in Yerevan on April 25, 2002, Ambassador V. Kazimirov, a former Russian representative of the OSCE Minsk Group, said:“The resolution of the Karabakh conflict is unlikely to be purely legal, it is likely to be political with other factors, including legal ones taken into consideration. That is why pragmatic solutions to disputable questions are more useful than framework discussions about principles”12. It is another matter what legal force this political decision will have for the future generations of the two republics13.