The last two years have been marked by expectations over the consequences of the “color” revolutions in Georgia in November 2003 and in the Ukraine in January 2005 and what changes may come in the geopolitical situation in the post-Soviet area. It is considered that these two revolutions should lead to the greater reorientation of these countries from Russia to the West. Although this process is far from being so unequivocal and besides, it is far from being complete, but the following events draw attention. Even before the “color revolutions” in Georgia and the Ukraine, the United States made a decision to allocate financial assistance to GUAM. At a summit of this organization in Chisinau, Moldova in the spring of 2005, appeals for a large-scale offensive of “color revolutions” in the post-Soviet area were made. In August 2005 the Presidents of Georgia and the Ukraine, Mikhail Saakashvili and Viktor Yuschenko, initiated the establishment of a new interstate union called “the Democratic Choice”, including the Baltic states and some states of the Black Sea Coast. Overcoming the authoritarianism of the post-Soviet area was one of the stated purposes of the future organization, a sort of “Arches of Democracy” from the Baltic Sea to the Caspian Sea (Azerbaijan had been invited to join the new structure). On the other hand, Russia was also invited (at the CIS summit in Kazan at the end of August 2005) which makes the contours of this yet emerging organization not quite clear). Parliamentary elections in Azerbaijan scheduled for November 2005 should give the answer to the question: which way – revolutionary or evolutionary – will prevail in the post-Soviet area?

Moscow’s direct military-technical collaboration with Teheran and the formation of a sort of alliance by Russia, Iran and Armenia are intended as a response to the West’s challenge. Islamic Iran renders support to the Republic of Armenia and has cool relations with the Azerbaijan Republic. Iran has consistently opposed the US policy of penetrating the regions of the South Caucasus and Central Asia and, unlike the Russian Federation, is not burdened with the rhetoric of recognising the democratic values of the West. The dragging out of the solution of the status of the Caspian Sea also contributes to the efforts of Moscow and Tehran to oust the US from the region1112. They are periodically confirmed by Iran’s declarations about its non-recognition of the oil contracts of the Azerbaijan Republic with the West. The latest example was in the summer of 2001 when the Iranian navy forced Azeri geological survey ships and representatives of the British Petorleum oil firm to stop working in the disputed Azeri sector of the Caspian Sea that Iran claims. Iran’s tough position towards the Azerbaijan Republic is also explained by another factor – the presence of a considerable number of ethnic Turks-Azeris in northern Iran (according to different estimates, they number as many as about 20 million, or about 30% of the population of Iran), who can be provoked by external forces to secede. Iran, not least due to a special position of Western Europe countries, is skillfully balancing on the verge of having global sanctions imposed on it. The US initiated the subject of the “nuclear programme” of Iran, which it earlier used in Iraq, as another stage of pressure on this country. Against the background of a sharp rise in oil prices, the intrigue surrounding the existing and planned pipelines has reached its climax. Iran, deprived of participation in the extraction of Azeri oil through US efforts, does its best to develop cooperation with Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, thereby, trying to direct their oil and gas pipelines to Western Europe and the Far East via its territory.

Mass media extensively cover the possibility of a planned military invasion of Iran by the US with the purpose of establishing a friendly, Western-type democracy in this country and, naturally, for control over its oil potential. In this connection, discussions about the creation of US military bases in Georgia and Azerbaijan under the pretext of protection of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and communications became more active. Meanwhile, most recently officials of both the US government and the AR leadership have unambiguously emphasized that no negotiations for military bases are being conducted.

Traditionally, exports of Azerbaijani oil, except for the low-capacity Baku-Batumi pipeline, have gone to the European market via the Baku-Novorossiysk pipeline. The new Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, whose cost was estimated at about $3 billion (in reality it proved to exceed $4 billion), will pump Caspian oil bypassing the Russian Federation. It is clear that the “pipeline war” that broke out will substantially determine the course of political events in the region. It has become especially true in the wake of 9/11 that placed the regions of the South Caucasus and Central Asia in the very center of modern geopolitical processes. The semi-velvet revolution in Kyrgyzstan and the brutal events in Uzbekistan have precisely designated the vector of these processes, and Kazakhstan has confronted a strong necessity of rationally (from the point of view of politics) filling all existing oil pipelines of the region with its hydrocarbon resources.

It is worth mentioning that according to media reports, the widely advertised meeting of the presidents of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Republic of Armenia in Key West (Florida) in April 2001 was, as a matter of fact, an attempt at “specification of relations” between Russia and the US regarding their influence in the region, and not between the parties to the conflict around NK13.

The situation in the South Caucasus, as we have already pointed out, paradoxically bears comparison with the beginning of the 20th century, when Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia gained independence for a short period. Just like it was then, the republics are involved in an inter-ethnic confrontation accompanied by frequent military operations between them and within their borders. Will the outcome of the modern confrontation be any different from the sad experience of that time that deprived the countries of the South Caucasus of independence and furthered, with the tacit consent of the West, the establishment of the Soviet regime in the region? The answer to this question not least depends on the degree of understanding by the political elites of the South Caucasus of the lessons of the past experience. Will the elites of the three countries be able to overcome their political ambitions and irrepressible lust for personal enrichment to find an opportunity for the integration of the region into the global political and economic system which is currently going through the processes of formation of a new order? Of course, it is not the early 20th century today, but to deprive independence of its real contents, to turn the republics of the South Caucasus into vassals and hostages of alien political ambitions and interests is quite possible.

And for the time being, the region is united by the common phenomena of hopelessness, neediness and despair among the population, as unemployment, mass emigration, monstrous corruption, clanship and authoritarian methods of government revived by former Soviet party functionaries who crammed during short-term courses the western slogans of democracy and free market. These are the real results of the ethnic confrontation, and they are not final either, because the desert sands are already spreading across the whole South Caucasus territory, which was abandoned by between three to five million people in search of work and a peaceful life. And the economic growth observed in Armenia and Azerbaijan during the last several years has little impact on the well-being of the population of both countries, but has only generated new stereotypes which are adverse for the cause of peace. In Armenia, it is that it is possible to develop successfully without establishing peace along the borders with Azerbaijan. In Azerbaijan, it is that petrodollars will make it possible to strengthen the army and to win back Nagorno Karabakh.

The seemingly transient conflict may last for decades, becoming latent, swallowing more and more victims. The genuine democratic education of the population and protection of democratic values in the region is the only possible means for reviving it in the third millennium. It is another matter who is going to do that and how it will be done!

Still, before the coming of the 21st century began, mankind has little by little begun to profess the philosophy and culture of peace and that was not because of good life. The first shoots of this culture are too weak to find their way to the sunlight through a thick centuries-old forest of the cult of war and violence. It is hard to say when and how this symbiotic existence will reach its outcome, but the fact that the only path to survival is in the rationalism of culture of peace as opposed to the irrational culture of war is out of the question. Those who have not realized it, those who profess the surgery of war very soon themselves become victims of its sharp and ruthless scalpel.

________________________________________

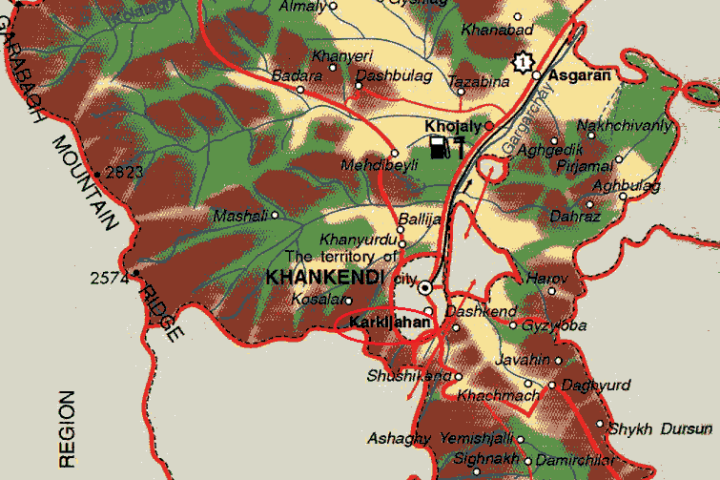

1A favorite aspect of the Azeri propaganda – the “rounding up” of figures for the sake of exaggeration. Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Region made up 5% of the territory of the Azerbaijani SSR, but not all of it is under control of the Armenians now. Outside it the Armenians have occupied about 9% of the territory of Azerbaijan. Together it makes less than 14% (and even if they round up this figure then 15 or 10 is much nearer to the truth than 20). The number of displaced persons in Azerbaijan is enormous (about 800,000 people), but propaganda all the time “rounds up” thefigure to one million. Regular overstating of reliable data (rather impressive as they are!) as a result only undermines trust towards Baku. (V.K.) Back to text

2The Armenians, in their turn, even though inertly but still try to deny the participation of regular troops of the Republic of Armenia in the military operations, covering it by the participation of volunteers and the like. For serious investigations of the Karabakh conflict this fact is indisputable. Another bend of the Armenian propaganda is the unwillingness to admit that territories outside Karabakh are occupied, seized or taken by them during battles, and obtrusive attempts to represent them even as “liberated” (V.K.)Back to text

3The co-authors here and then use almost as synonyms the words “conflict” and “problem” whereas they are different notions. For example, the problem of NK might not have ended in an armed conflict. The escalation of the parameters of this conflict (“levels”) engaged new actors to its settlement and, no doubt, had an influence on its course, but not so much on the ways of solving the conflict. (V.K.)Back to text

4In October 2005, just before the publication of this edition, Ilham Aliyev, apparently, initiated steps to change the team he inherited from his late father (comment of the 3rd edition).Back to text

5By external forces the authors obviously imply Russia as well. It is important to emphasize that the pro-Russian orientation of the Karabakh Armenians has long historical roots and does not only result from the last decade. Besides, a natural inclination of the Karabakh people to Russia is, undoubtedly, stronger than the inverse vector.Back to text

6As it was already mentioned in the foreword, the authors’ hypothesis that the Center pursued this policy is very doubtful (V.K.).Back to text

7The extremity of the authors’ judgements regarding Russia’s policy towards the conflicts in the Trans-Caucasus causes bewilderment. The real feeding of the conflicts from inside and outside: bloody hostilities and increased animosity, division and seizure of Soviet armament in the Trans-Caucasus, recruiting of mercenaries, breaking of armistices, support of the conflicts from the West first to weaken the USSR and after its collapse to penetrate the Trans-Caucasus are pushed to the background. The authors are not always logical: they ascribe to Russia multiform interest in the three Trans-Caucasian conflicts and have to acknowledge Russia’s decisive role in the discontinuance of bloodshed in all three conflicts. (V.K.)`Back to text

8Pay attention to this calm assertion by the authors: there is not a shadow of condemnation of the West’s proclamation of the region of “newly independent states” as an object of its claims. (V.K.)Back to text

9The wording is not quite exact. But the thing is that Levon Ter-Petrosyan intended to seek a compromise with Azerbaijan at the cost of concessions and by stages, assuming the Armenians’ pullout from some of the occupied regions of the Azerbaijan Republic before the question about the NK status was solved. (V.K.)Back to text

10According to the data of the October 2002 census, the number of those who left Armenia was between 800,000 to 900,000.Back to text

11Russia has already signed bilateral agreements with Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan about the principles of division of the Caspian Sea. But there are still disagreements with the two other coastal states – Iran and Turkmenistan.Back to text

12The very fact that Russia reached the agreements on the division of the Caspian Sea with both of its neighbors – Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan shows as groundless the ascription of Moscow to those that delay the resolution of the question about the status of the Caspian Sea. And Teheran doesn’t oust the US from the region either, rather it tries to prevent it from penetrating there. The vocabulary is in itself revealing here. (V.K.)Back to text

13The co-authors see in everything the clash of interests of Russia and the USA as an axiom. Mutual understanding and cooperation on the Karabakh settlement among the co-chairmen of the OSCE Minsk Group before and during the meetings in Key West were quite normal. (V.K.)

[no_toc]