3. Assessment of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict upon the relevant documents of international law

Assessment of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not possible without analyzing relevant norms and principles of international law. The importance of this issue is explained by the fact that it covers the contradiction between two important principles of international law: territorial integrity of states and self-determination of peoples.

3.1. Regulation of self-determination by international law

After World War II, the right to self-determination began to change from political concept into legal principle. This principle began to be reflected in fundamental documents of the contemporary international law. As an example, we can refer to the UN Charter, Covenant on civil and political rights as well as Covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. But issues concerning the right to self-determination are not explained in details in these specific documents. Therefore, the UN General Assembly pledged itself to resolve this task. In this connection, we can enumerate resolutions of the UN General Assembly 1514 (ХV), 1541 (ХV) and 2625 (ХХV). These resolutions established close relationship between the right to self-determination and the process of decolonization, and the International Court of Justice confirmed that this aspect of the right to self-determination constituted a part of international law. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned, that there are significant differences between the provisions of resolutions 1514 and 2625.

It becomes evident from the text of several international documents that the right to self-determination goes beyond the notion of colony. Article 1 of the above mentioned Covenants state that peoples enjoy the right to self-determination.[ref]International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976) 999 UNTS 171, 173; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1976) 993 UNTS 3,5[/ref] Resolution 2625 states that the right to self-determination is the right, which can be applied to all peoples and is the duty, which shall be followed by all states.[ref]Christian Tomuschat „Völkerrecht“, Baden-Baden 2001, p.81.[/ref] It should be mentioned that the nature and character of the right to self-determination can always cause tension among the states.

3.2. Contradictions between the right to self-determination and territorial integrity

According to some international lawyers, there is a conflict between the principles of self-determination and territorial integrity. This approach to the issue raises a question which of these principles should prevail. It should be pointed out that nearly in all international legal documents provisions stipulating the right to self-determination are followed by the provisions emphasizing inviolability of borders and territorial integrity of sovereign states. For example:

The General Assembly (GA) Resolution 1514 (XV) „The Declaration on Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples“, Abs. 6: “Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations”.

Helsinki Final Act dated from the 1st of August 1975 also limits self-determination by territorial integrity of states. 8th principle of this act on equal rights and the self-determination of peoples states:

“The participating States will respect the equal rights of peoples and their right to self-determination, acting in all times in conformity with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and with relevant norms of international law, including those relating to territorial integrity of States”.

Obligations reflected in this document have were further reiterated in the Paris Charter (1990), Final Declaration of the Lissabon Summit (1996) and the European Security Charter (Istanbul Summit). All these provisions allowed some lawyers and states to prove the prevalence of territorial integrity over self-determination. Moreover, it was suggested that provisions of resolution 1514 only apply to «the peoples of colonies». Professor Gros Espiell wrote in this connection: „The right to self-determination of peoples does not apply to peoples which are not under colonial or alien domination, since Resolution 1514 (XV) or other UN instruments condemn any attempt aimed against…territorial integrity of a country”. Conclusion stemming from such logic is that today self-determination is of no importance, as there are no colonies any more. Nevertheless, such interpretation of self-determination is rejected. Because, this interpretation would pose a danger on universality of this principle as per clause 1 of resolution 2625, which stipulates self-determination as a fundamental right for all peoples. However, even in this document self-determination is limited by conditions on territorial integrity. Clause 7 of this resolution says:

“Nothing in the foregoing paragraph shall be construed as an authorizing or encouraging any action, which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political union of sovereign and independent States conducting themselves in compliance with the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples as described above and thus possessed of a government representing the whole people belonging to the territory without distinction as to race, creed or color”.

Having read this provision thoroughly, one can say that this could serve as the only provision, to which the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh might refer. However, as mentioned above, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh blaimed official Baku for social-economic discrimination and cultural exploitation. In fact, this provision of the resolution 2625 does not prohibit a secession as a result of an internal conflict. When reading this provision from the aspect of the right to self-determination as a human right, we may conclude upon textual interpretation of the resolution that secession is not prohibited as an action in contradiction to international law. As such, provision concerning protection of territorial integrity of states envisages a reservation which states that territorial integrity of a state is protected if it respects the right to self-determination and possesses a government representing the whole people belonging to the territory without distinction as to race, creed or colour. We should mention with regard to this provision, i.e. representative government, that Nagorno-Karabakh was the only autonomous region in the USSR, represented in the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan SSR by deputy chairman. In general, Nagorno-Karabakh was represented in the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan SSR by 10 MPs of the Armenian nationality.[ref]Interestingly, on 17th June 1988, as the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijanian SSR rejected the request on secession of Nagorno-Karabakh from Azerbaijan, 17 MPs of the Armenian origin from constituencies beyond Nagorno-Karabakh also voted for this decision. See, O. Luchterhandt „Das Recht der Berg-Karabachs Armenier auf Selbstbestimmung aus völkerrechtlicher Sicht“. Hamburg 1992, p.14[/ref] Moreover, number of the Armenian MPs in the Regional Council of Nagorno-Karabakh exceeded the number of the Azerbaijani MPs due to predominance of the Armenian population in the region.[ref]110 MPs out of 140 were Armenians by nationality. See., O. Luchterhandt, p.13.[/ref]

According to Karl Doehring, a German international lawyer, ethnic groups may have the right to secession only if they are exposed to an excessive discrimination. This means that in case of systematic gross violation of human rights and absence of any state mechanism against such violation, national minorities can benefit from the right to self-determination and establish their own state. But, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh was not exposed to any violation of human rights and their actions bear separatist character.

3.3. Was the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh entitled to secede from Azerbaijan for establishing their own state as national minority?

a) Difference between the notions of people and national minority

After collapse of the USSR the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh has changed their previous position. If previously they aimed at a secession from Azerbaijan and annexation to Armenia, now they claim to establish an independent state upon the right to self-determination of peoples. However, in this case it is important to take into consideration the difference between the rights of «peoples» and «minorities». In all documents of international law the right to self-determination is granted only to peoples. “People” is any group living on the territory of any state and building majority of its population. Only in this sense people are entitled to self-determination and creation of their own state. As to minorities (national, ethnic, linguistic, religious, etc.), they are not entitled to determine their political status. In this connection, Art. 27 of Covenant on civil and political rights states:

“In those states in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion, or to use their own language.”

Declaration of the UN GA on rights of national, ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, dated from 18.12.1992, does not either grant to minorities right to self-determination. Article 2 of this declaration contains a similar provision on the rights of minorities. Article 8 para. 4 of the declaration is as follows:

“Nothing in the present Declaration may be construed as permitting activity contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations, including sovereign equality, territorial integrity and political independence of States”.

The Armenian population, living in Azerbaijan, are ethnic minorities like Russians, Georgians, Ukrainians, Jewish and other ethnic minorities.[ref]Armenians comprise 2% of the total population of Azerbaijan.[/ref] The Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh can be afforded only above mentioned rights (Art. 27 of the Covenant). This means that they are entitled to determine their status for effective participation in political, social, economic, cultural, religious and public life of Azerbaijan. They may not commit any action, which might pose a danger to sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Azerbaijan according to international law.

b) Examples from history

In 1921, as the dispute over territorial integrity of Finland and the right to self-determination of the population of Åland Islands (Ahvenanmaa), mainly consisting of Swedes, was investigated, a report of International Lawyers’ Commission prepared for the Council of the League of Nations, concluded that compared to Finns the population of Åland Islands was just a «national minority», not «people». The report of the commission stated furthermore that regulations applied to the people can not be applied to minorities. The most important conclusion was that minorities are not entitled to self-determination.[ref]Report of the International Commission of Jurists (1920) LNOJ Spec. Supp. 3; The Åland Islands Question: Report Submitted to the Council of the League of Nations by the Commission of Rapporteurs (1921) League Doc. B7.21/68/106, 27[/ref] This report was submitted to the Council of the League of Nations. The Council approved the report and attached it to its resolution. According to that resolution, sovereignty of Finland over Åland Islands was recognized. The resolution also called for according of guarantees to the inhabitants of the island and achieving of an agreement over the neutral status of the island.[ref]

The other example is more recent. On August 27, 1991, the European Communities, taking into consideration the processes in the former USSR and Yugoslavia, adopted declaration. According to the declaration, the European Communities would never recognize the frontiers, which were not established through peaceful means i.e. negotiations. The declaration established a Peace Conference and Arbitration Commission of the EC for Yugoslavia. Opinion 2 adopted by the Commission comments on the possibility of application of the right to self-determination to the Serbian people of Croatia and Bosnia-Hersogovina. The Serbian population on these territories constituted 1/3 of the total population. The opinion rejected the demand of the Serbian people for the right to self-determination. In its opinion, Arbitration Commission declared „that the Serbian population in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia must be afforded every right accorded to minorities under international conventions as well as national and international guarantees consistent with the principles of international law…”[ref]31 ILM 1497 (1992), paragraph 2. Moreover, European Union has adopted declaration on recognition of newly-established states in Eastern Europe and Soviet Union.[/ref]. Thus, prevalence of the principle of territorial integrity over self-determination was declared once again. First part of the opinion states:

„It is well established that, whatever the circumstances, the right to self-determination must not involve changes of existing frontiers at the time of independence except where the states concerned agree otherwise.”[ref]Again there.[/ref]

Issue of frontiers is also important in assessment of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Because, representatives of both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh are constantly claiming that Nagorno-Karabakh has never been within independent Azerbaijan and borders during the Soviet period had exclusively administrative nature. By such statements they are trying to justify separatist actions of the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh. Such problem arose also in the former Yugoslavia and it can be called “irredentist demand”[ref]Irredentism is a movement of an ethnic group, living on the territory of a state, which strives to secede from that state in order to be included within the boundaries of another state where the ethnic group constitutes majority.[/ref] in legal terminology.

c) Role of the Principle Uti possidetis iuris in this regard

During dismembration of Yugoslavia the above mentioned Arbitration Commission of the EC referred to the principle of uti possidetis.[ref]In 19th century when Spanish colonies gained independence in Central and Southern America, they acted on the principle of uti possditetis iuris (Uti possidetis, ita possediatis – what You have, You possess it). The essence of this principle was that borders of the former Spanish provinces remained as borders of the newly established states.[/ref] In other words, this principle was applied in order to limit the boundaries of the newly established independent states, This principle envisages that frontiers of the territories, which are not subject to self-government, remain unchanged after they gain independence. Although this principle was in particular applied in the processes of liberation from colonies[ref]During the processes of liberation from colonies in Africa, Conference of African states, held in Cairo in 1963, adopted a decision about not changing borders of former colonies and keeping borders of newly established states within the limits of former colonies.[/ref], Arbitration Commission of the EC declared that uti possidetis has already gone beyond the context of colonies and become a general principle. To substantiate its position once again, the Commission referred to the case concerning the frontier dispute between Burkina Faso and Mali, decided by the International Court of Justice[ref]Case Concerning the Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali) Judgement, ICJ Reports 1986, p. 554-565[/ref] Here, the judgement of the International Court of Justice was based on the principle of uti possidetis:

“Nevertheless the principle is not a special rule which pertains to one specific system of international law. It is a general principle, which is logically connected with the phenomenon of the obtaining of independence, wherever it occurs. Its obvious purpose is to prevent the independence and stability of new States being endangered by fratricidal struggles”[ref]Ibid[/ref].

It can be stated in general that if the Nagorno-Karabakh issue is brought before the International Court at any time, then we may say with confidence that the decision will be in favor of Azerbaijan under the principle of uti possidetis. However, it should also be mentioned that since Azerbaijan and Armenia do not recognize compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice according to Art. 36 para. 1 of its Statute, or due to the absence of special agreement between the parties on submission of the dispute to the International Court and in general, since the Republic of Armenia denies its involvement in this dispute as a party, possibility of submitting the dispute to the ICJ is at zero yet.

Conclusion

Summarizing the above mentioned, we can classify the evidences against separatism as follows: 1. The right to self-determination of people can only be exercised on the basis of the maxim pacta sunt servanda (treaties must be respected); 2. International Law is the law of states and not of peoples or individuals. States are the subjects of international law and peoples are the objects of that law; 3. The so-called principle of reciprocity; as a state cannot oust a part of itself, equally a part of the state cannot forcefully secede from that state.

Such approach to self-determination reflects the position of majority of countries, which are able to protect their territorial integrity. As such, usually, if there is a discrepancy between territorial integrity of any independent state and self-determination of any national minority, living on the territory of this state, only internal self-determination (i.e. granting autonomy) can be taken into consideration. Any claims, which demand that the principle of self-determination should support secession of any part of state from it, have always been rejected. With only exception of Bangladesh (in that case, without interference of the Indian army Bangladesh could not have gained independence), no other separatist claim has been accepted by the international community since 1945. As it is evident, Bangladesh events did not serve as precedent, these events were mainly explained by «oppression theory». Linguistic, ethnic and cultural differences of Bengalis and geographical separation of the territory from Pakistan served as a ground for establishment of the state of Bangladesh according to above mentioned theory (around one million people were reported to be killed during the conflict).

3.4. Assessment of the referendum, held on December 10th 1991 in Nagorno-Karabakh, in terms of international law

Coup d’etat, committed in August 1991 in Moscow, served as a signal for most Soviet Republics. This was followed by the processes of secession from the USSR and the Soviet republics declared their independence.

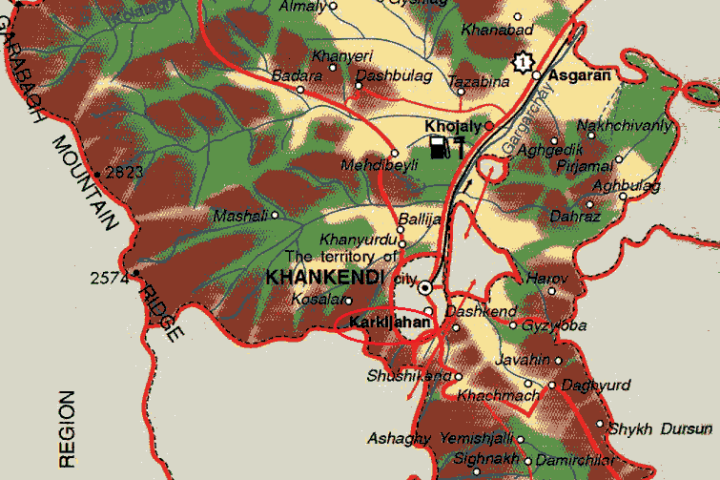

On September 2nd of the same year the meeting of the Regional Council of Nagorno-Karabakh declared the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region as a new Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh. The meeting was held without participation of the Azeri delegation. On November 26th of the same year Azerbaijan reacted to this illegal action by cancellation of the autonomous status of Nagorno-Karabakh. The so-called republic held referendum on independence on December 10th and declared its independence on January 6th of 1992.

As for legitimacy of this referendum, held in Nagorno-Karabakh on ethnic basis, the Armenian side refers to the Law of the USSR dated 03.04.1990 on «Procedures for resolution of the issues related to secession of Soviet Republics from the USSR». It should be noted, that this law itself was contrary to the Constitution of the USSR, because it contradicted the above mentioned Articles (78, 86, 87) of the USSR Constitution. Art. 3 of this Law, which is based on the principles of Leninism and which supports self-determination of not only peoples, but also of ethnic minorities (including secession from any state), envisaged right to self-determination for autonomous regions of the Soviet Union, too. However, Armenia’s position on legitimacy of this referendum had no substantiation both in national and international law. As such, there is a fact, which is obviously ignored (may be deliberately) by the Armenian side in connection with this matter: when the referendum was held (10.12.1991) Azerbaijan was an independent state. Therefore, provisions of the above mentioned Law could not be applied to the independent Republic of Azerbaijan and its territory.

Secondly, the Armenian side can not substantiate legitimacy of their secession from Azerbaijan by oppression theory (i.e. for the reason of discrimination of the Armenian people of Nagorno-Karabakh). Even if there were facts of discrimination, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh could not refer to it. Because, in the former Soviet Union government was rather centralized and local governments (Republics of the Union) were directly subordinated to the instructions of the Kremlin. Moreover, the Armenians and the Azerbaijanis of Nagorno-Karabakh had joint administration council in Nagorno-Karabakh. The Head of the Council was Armenian by nationality, there were Armenian schools in the enclave, welfare of the population was very good and etc. Taking all these into consideration, we can insist that any fact of discrimination towards the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh is out of question.

Thirdly, this referendum is neither legitimate from the point of view of valid international legal regulations, as the referendum was held without consent of the independent Azerbaijani state exclusively on an ethnic basis. Ethnic principle of self-determination has never been taken as a serious factor by international community in assessment of any claims against a state. Moreover, ethnic principle of self-determination can not be considered legitimate without consent of all related parties, because the referendum, held on this basis is of discriminative character by itself. If the Armenian population, living in Nagorno-Karabakh expresses their wish of independence through self-determination, then this wish should raise a suspicion as the fact of their ability of self-determination. As mentioned above, on the threshold of the conflict, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh did not aim to gain independence at all, their major intention was to annex Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. There are many facts which prove irredentist character of the intention of the Armenian population. Appointment of the Minister of Defence of the so-called Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh Serj Sarkisyan as the Minister of Armenia in 1993, election of Robert Kocharyan (although he remains a citizen of Azerbaijan from the legal point of view) as the President of the Republic of Armenia in March of 1998 and February of 2003, non-cancellation of the resolution of the Supreme Soviet of the Armenian SSR dated 01.12.1989 on annexation of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, involvement of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Armenia in this conflict and other evidences prove that the conflict bears irredentist character and is closely connected with the issue of territorial integrity. Naturally, when we consider the conflict from this point of view, we should treat it as an international armed conflict and the Republic of Armenia should be accepted as an aggressor.