[toc]

ABSTRACT

International terrorism, proliferation of WMD, mounting nationalism, and ethnic separatism have already become part and parcel of the contemporary political processes unfolding with frightening speed.

Ethnic separatism in the Southern Caucasus is a local manifestation of the global struggle over the world markets. Any analysis of the region’s future stumbles across the problem of settling the region’s ethnic-separatist discords, the main one of which is the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This means that an analysis of corresponding international experience may suggest fresh approaches to the old conflict.

The conflict cannot be resolved at the cost of the territorial integrity of one of the sides: the solution lies in preserving and encouraging the national minority’s ethnic specifics within the unified state.

Introduction

The disintegration of several polyethnic states and the high destructive potential of nations which have lived side by side for a long time in one state suggests that ethnic separatism is not a national or even regional threat: it is developing into a global security hazard. The expert community is convinced that the ethnic separatism issue is one of the major problems of the day and will keep the world community involved in its settlement throughout the first decades of the 21st century.

As a rule, ethnic extremism mounts during social and economic crises which cause social differentiation, a power struggle, and a wave of crime. External extremist structures invariably present in all hot spots fan the fire of ethnic nationalism by encouraging national strife.

The world community has already tested all methods of crisis settlement ranging from diplomacy to the use of force; in some cases it supported one of the conflicting sides, in others it internationalized the conflict by drawing international observers and the U.N. peacekeeping forces into the settlement effort. Some of the conflicts were settled, however, we should admit that the world community still lacks effective instruments (legal norms and the mechanisms to implement them), the use of which will make the settlement process predictable and sanctions against those who violate them inevitable.

Though similar to separatist movements elsewhere in the world, South Caucasian ethnic separatism was born from very specific phenomena. It is a local manifestation of the global battle for the world markets, which means that today the struggle for political and economic control over the Southern Caucasus has become one of the central factors. This makes an analysis of international experience in settling ethnic-separatist conflicts and its correlation with the efforts to settle the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan especially interesting.

Ethnic Separatism in Europe

The Åland Islands

The status of the Åland Islands, a territory that was an apple of discord between Sweden and Finland in the 1920s, is the first more or less important precedent of settling territorial issues. After becoming independent in 1917, Finland discovered the problem of the compact Swedish-speaking population on the Åland Islands, which for many centuries belonged to Finland’s sphere of interests and were part of the Grand Duchy of Finland.

After discussing the problem, the International Committee of Jurists of the League of Nations confirmed Finland’s sovereignty over the islands. The final document said: “Positive International Law does not recognize the right of national groups, as such, to separate themselves from the State of which they form part by the simple expression of a wish… Generally speaking, the grant or refusal of the right to a portion of its population of determining its own political fate by plebiscite or by some other method, is, exclusively, an attribute of the sovereignty of every State…,” and added that to allow linguistic or religious minorities or any other part of the population to withdraw from the society to which they belong merely because of their wishes or good intentions would mean a breakdown in domestic order and stability and the encouragement of anarchy in international affairs; this would mean support of a theory incompatible with the very idea of the State as a territorial and political entity.1

The League of Nations granted autonomy to the Åland Islands, the population of which acquired more than they wanted and probably even more than if they had joined Sweden: a clearly stated status confirmed by the League of Nations, the highest international instance, and autonomy instead of the status of another Swedish province guided by Swedish laws. By remaining within Finland the islanders preserved their culture and profited economically.

The ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh could have gained the same had they stayed in Azerbaijan.

The Balkans

Today, the area known for the last few centuries as the powder keg of Europe remains the most volatile region on the continent.

Among the variety of methods employed in conflict settlement in the Balkans, the Croatian experience in dealing with the Serbian separatists deserves special attention. Let’s go back to the very beginning. The Serbs of Serbską Krainę exploited the fact that the Serbs were in control of the former Yugoslav army to declare their separation from Croatia and drive the Croats from their territory. Franjo Tudjman, who was president of Croatia at that time, demonstrated a lot of good sense when he agreed to a ceasefire and permitted a U.N. peacekeeping contingent to enter the country. Later, with open German and latent American support, he rearmed and reformed the army and offered the Krainę Serbs economic, political, administrative, and cultural autonomy. Too sure of their military might, the Serbs flatly declined the offer and were routed by the Croats with the mute consent of the West.

Speaking at a briefing at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, Foreign Minister of Armenia Vartan Oskanian compared the events in Kosovo and Nagorno-Karabakh (NK). The local Armenians, he argued, as well as the Albanians of Kosovo, were subjected to ethnic purges. Armenians, said the foreign minister, accomplished what NATO should have done: it prevented ethnic purges of the Armenians of NK.2

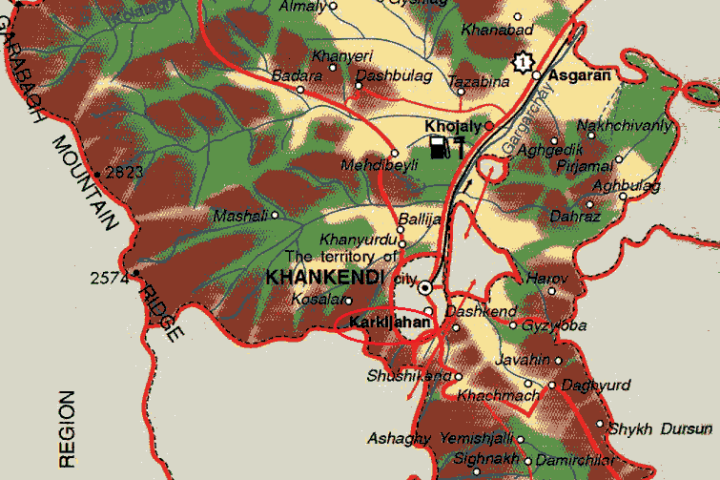

Any impartial observer can say that it was the autochthonous Azeri population of NK that was subjected to ethnic purges and was driven out of their homes by force. Aided by Armenia and other external forces, the Armenian separatists of NK established their power in the area and occupied seven adjacent administrative units of Azerbaijan, pushing out about one million local Azeris. Logic suggests that the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh was not subjected to ethnic purges. The instances of extermination of the civilian population of Malybeyli and Gushchular and genocide in Khojaly testify that it was not the Armenians who were subjected to ethnic purges in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Armenian aggression against Azerbaijan and ethnic purges of the Azeris in Armenia and Azerbaijan created the continent’s most acute humanitarian crisis. In the spring of 1999, fully aware of the dimensions of what they had done, the Armenians staged numerous mass rallies to protest against NATO’s actions in Yugoslavia under the slogans, “No to Bombardment of Belgrade” and “After Belgrade—Stepanakert.”

It should be said in all justice that unlike Belgrade, which denied the Albanians of Kosovo complete self-government, Azerbaijan was at all times prepared to grant the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh this right. For some reason, the international community still looks at Kosovo as part of Serbia—a position testified by the resolutions of the U.N. Security Council and the decisions of international organizations. As distinct from its treatment of Montenegro, Serbia is not allowing Kosovo to detach itself. As for Montenegro, official Belgrade recognized the results of the referendum on the province’s separation from the common state of Serbia and Montenegro. In other words, Montenegro left the common state with Serbia’s consent. In fact, the document that set up the common state envisaged that Montenegro could leave it if its nation so desired.

The Balkans is the only exception in relatively stable Europe, although ethnic separatism is not completely absent.

Western Europe

Catalonia in Spain, Corsica in France, and Northern Ireland in Great Britain are the hottest seats of ethnic separatism in Western Europe.

Catalonia

The Basques, a large people by European standards (they number about a million) who live in the Pyrenees and piedmont area on both sides of the Spanish-French border, are justly considered to be the main troublemakers of Europe. For over half a century now the Basque separatists of the ETA group (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, which means Homeland and Freedom) have relied on terror to force Spain and France to recognize their independence.

The Basques are a unique ethnos who speak a language different from the European tongues. Their territory became part of Spain in the 14th-15th centuries.

Never loyal subjects of the Spanish crown, they ignored the Spanish laws as well. The idea of an independent state dates back to the late 19th century when the national movement for the autonomy of the Basque Country within Spain began to take shape. In 1931, the Basques received autonomy from the republican government; Franco abolished the Basque autonomy and forbid the local language in official structures and even at home. This caused a storm of indignation that has not yet subsided.

The ETA, a terrorist organization, emerged at the turn of the 1960s in response to the rout of the main forces of the Basque partisan movement by government troops. The Basque fighters made terror their main weapon, but they were never alien to robbery. Kidnapping and indiscriminate extortion of money for the revolutionary cause, even from Basque businessmen, were no less important than fighting the Franco dictatorship.

It seems that business based on terror proved to be a profitable enterprise: at least in 1979 when the area regained its autonomy, the ETA refused to leave the scene. It announced that it intended to fight for independence. Its restored autonomy allowed the ETA to set up a political structure called Eri Batasuna (People’s Unity) which could run for the local parliament to defend the terrorists’ interests there. The Spanish authorities consistently refused to talk to the terrorists, while not encroaching on their local autonomy.

In 1998, the ETA announced that it intended to abandon its terrorist activities fully and forever; the authorities held confidential talks in Zurich and liberated some of the activists. Fourteen months later, the separatists violated the truce, probably because radicals had gained the upper hand in the organization.

The government resorted to the harshest political measure at its disposal and banned Batasuna in August 2003.

On 22 March, 2006, the ETA announced a permanent ceasefire and its willingness to hold a peaceful dialog with Madrid.

In July 2006, the ruling party of Spain and the banned Batasuna held their first peaceful talks about the peaceful settlement of the Basque problem, which over 38 years had claimed over 850 lives. At the first stage it was expected that the Batasuna leaders would officially condemn terrorism and denounce their former violence. For the first time in their history the party publicly denounced violence as a means of political struggle.

Madrid was fully aware that by exchanging official condemnation of terrorism by the former terrorist party for its legalization and its later inclusion into the political process, it was allowing the party to insist on a referendum about the future of the Basque Country. To forestall these developments, the Spanish authorities repeatedly hinted that the Basques could only count on wide autonomy, not independence.

Significantly, according to the latest polls, 75 to 80 percent of the Spanish believe that peace can be achieved through talks.3

Corsica

The Island of Corsica, 8,700 sq km in area, is another hot spot of sorts in Western Europe. Its population of about 300,000, which speaks an Italian dialect, has been demanding independence from France for several decades now.

Corsica is one of the most backward EU regions; in the 21st century the local people have preserved their extremely archaic social forms. The island became part of France in the 18th century, yet at no time it was a fundamental part of continental France, the power of which was always relative.

For a long time Paris preferred to ignore its demands for autonomy; French legislation in fact does not presuppose the existence of any ethnic groups in France: the French is a blanket term applied to all French citizens. In practical terms this means a ban on teaching native languages in schools.

The National Front for the Liberation of Corsica, the island’s largest terrorist organization guided by separatist slogans, was set up in 1976; it has already murdered several thousand people (mainly members of the French official structures). There are about twenty other terrorist organizations on the island. Terrorist acts follow one another: several dozen blasts every year. The authorities are at a loss: the recently granted autonomy merely encouraged the terrorists to ask for more.

In the last twenty five years the island changed its status twice: in 1982, it received a special status that gave the local self-government a free hand in agriculture, energy, housing construction, transport, education, and culture. In 1990, Corsica became an administrative-territorial unit in which the elected self-government structures enjoy wider powers.

Recently the National Assembly of France conducted a series of parliamentary debates on the island’s future. The government announced that its draft law would promote civilian peace in Corsica. Some of the deputies disagreed: they were convinced that the Cabinet had gone too far in granting rights and power to the local self-government structures. In fact there is no agreement on the Corsica issue.

The island remains one of the worst headaches in France; terrorist acts have become a common feature of the local social landscape: one can always expect blasts in public places or even political assassinations.

By placing wider powers on the agenda, the government hoped to finally break the “vicious circle of violence.” It seems that those who rule France hope that it will be easier to cope with the terrorists deprived of their stated cause of protecting the islanders’ national specifics and rights.

Some observers believe that the Corsica project is in full accord with the “modern ideas of democracy” and the “least of the evils” in the context of permanent turmoil. Other experts are convinced that the government merely encouraged the terrorists, they argue that the draft law is an “award for violence.”

According to public opinion polls, 46 percent of the French do not believe that these measures will restore peace and order on the island; 61 percent of the respondents object to the transfer of legislative functions to the Corsicans; and 66 percent of the respondents object to teaching the Corsican language in primary schools.4

Northern Ireland

The Irish conflict attracts much more attention in Europe than those described above. Today, it seems to have lost some of its acuteness (it reached its peak in the 1970s) and is moving toward a settlement. This example and the experience of dealing with similar conflicts in this part of the world could have been used elsewhere to resolve more recent problems.

It should be said that an independent state (or rather a conglomerate of state formations, a certain federation with a nominal central power) on the island dates back to the early years A.D.

In the 12th century, the island was invaded by several waves of Angles and Normans; it was at that time that the Pope proclaimed Henry II King of England and Ireland. For the next two centuries the Irish successfully assimilated the invaders. In the 16th century, however, King Henry VIII decided to tighten his power, so far purely nominal, over Ireland.

Ethnic confrontation was thus doubled by religious disagreement when Henri VIII broke all his ties with the Vatican to set up the Church of England (the English version of Protestantism). Catholicism in Ireland was first restricted and then ruthlessly persecuted.

It should be said that traditionally the Church is very strong in Ireland: Christianity was essentially never imposed on the local pagans, who were left free to combine the new religion with the local cults. Ireland was Europe’s second (after Rome) Catholic country, which means that the local people could not peacefully embrace Protestantism.

The centuries of English domination over Ireland were filled with riots, resistance, and mass emigration.

During World War I, while Britain was tied down on the continent, the Irish tried to liberate themselves. The country rebelled, while the Irish Republican Army (IRA) fought actively against the British troops and the police. The Home Rule Act of 1921 created the Irish Free State with dominion status; in 1949, Ireland gained its independence and left the British Commonwealth of Nations.

While the country’s southern part became politically independent, a large part of Ulster (so-called Northern Ireland) remained British.

Ulster is a historical part of Ireland, which includes 9 counties, 3 of which belong to Ireland and 6 to the UK.

Today, the 1.5 million-strong population of Northern Ireland is mainly Protestant, who do not regard themselves as Irish and find it hard to ethnically identify themselves: they call themselves either Ulster people, or loyalists, Unionists or (rarely) English Irishmen. This is the product of the English and Scottish colonization of Ireland in the 17th century as part of the English colonization policy: landed estates were taken away from their Irish owners and transferred to English and Scottish settlers.

In Northern Ireland, religion is also a social dividing factor: the Protestants and the Catholics are united into communities each with its own lifestyle, potential education and employment levels and, not infrequently, settlement areas.

For nearly fifty years, the Catholics, because of the fairly ingenious election system (designed to promote Protestant representation), were poorly represented in the parliament and the local administrative structures and were victims of discrimination: decent employment and housing were outside their reach. Secondary education was another sphere of discrimination: all schools belong to one of the religions: as a rule, the Protestant schools are better funded from private sources and, therefore, offer better education. The Catholic schools have to rely on municipal money, which until the 1970s-1980s deprived their graduates of the chance to enter colleges and universities. Hence discrimination on the labor market and lower living standards.

The British Cabinet never pondered on possible changes in Northern Ireland; during 400 years of its history, Great Britain never discussed the possibility of separation with any of its component parts.

In the 1960s, terrorist and semi-terrorist organizations started mushrooming in Northern Ireland, the Protestants being even more aggressive than the Catholics.

To alleviate the crisis and defuse violence and terror, London offered several reforms designed to improve the social and political situation of the entire population. It should be said, that for several decades the Catholic and Protestant communities underwent important, albeit slow, changes. Extremism became more “cultured” and socially oriented, which made cooperation and compromise, if not possible, then at least probable. Prerequisites for launching a peace process took many decades to surface: methods of peaceful settlement and for determining Northern Ireland’s political status were related to the political parties and groups and the governments of the U.K. and Ireland.

In April 1998, the government and the parties of Northern Ireland reached the historic Good Friday Agreement, under which Northern Ireland remained part of Great Britain, while the Irish Republic dropped its territorial claims in the region. It was decided to set up the democratically elected Assembly of Northern Ireland with certain rights of self-government and common Irish power structures. Elections to the North Irish parliament were envisaged together with setting up the North/South Ministerial Council to promote cooperation between Dublin and Belfast, as well as the British-Irish Council.

In July 2002, the IRA publicly repented and asked for forgiveness for the numerous deaths and injuries it caused among civilians in all of its operations. On 28 July, 2005, the group officially announced that it had abandoned forever its armed struggle of over 30 years.

This is a positive example which proves that all conflicts can be solved peacefully and in a civilized way. Indeed, even in this conflict overburdened with many centuries of far-from-easy relations between Britain and Ireland and the fact that the former refused to talk to the separatists and terrorists under any circumstances, standing firm in the face of Irish protests, the sides preferred to seek a peaceful political and cultural solution. This gives hope to the sides involved in similar conflicts elsewhere.

Conclusion

An analysis of the roots of ethnic separatism and the role of the international community in settling ethnic conflicts indicates that the efforts to prevent such conflicts should be channeled in the following directions:

- Global and especially regional cooperation should be more active and go deeper, while states should pool their efforts to fight ethnic separatism;

- To neutralize this phenomenon, we need international and national legislation;

- The world community should reach an agreement on clearly stated and universally accepted criteria that will let the sides decide when force and when international legislation should be used to liquidate ethnic conflicts;

- The time has come to set up regional anti-terrorist centers and to invite armed forces and other structures to fight ethnic separatism and extremism;

- The social and economic situation in the countries and regions that remain seats of potential ethnic conflicts should be improved;

- All sorts of possible versions of the emergence and development of ethnic conflicts should be discussed in detail, so that all kinds of operational measures can be taken on time at the regional and global levels.

Only this will ensure the territorial integrity and sovereignty of states and their national interests in the 21st century, which promises no clemency to anyone.

One thing is clear: a state’s integrity should not be sacrificed to the peaceful settlement of any ethnic separatist conflict. Such settlement should restore and ensure the territorial integrity of the state in question, as well as preserve and encourage the national minorities’ ethnic specifics. The national minorities should not expect their problems to be resolved by setting up “ethnically purged states” or quasi-states for each of them. This threat cannot be removed by dividing states, rather by strengthening states and increasing the authority of international human rights organizations.

All conflicts unfold both in space and time; time adds legitimacy to territorial changes (even those achieved through violence). The world community tends to stabilize the new situation and very rarely sides with the losers who try to restore their rights through another war. The world should not grow accustomed to the thought that Azerbaijan can live without the occupied territories from which those who could have riveted the world’s attention by their incessant struggle have been driven by force. We need a long-term strategy that includes strengthening our armed forces, reviving the economy, and developing economic and political relations. Azerbaijan should become a strong and democratic state with a dynamic economy.

It is extremely important for it to preserve itself as the state of a certain cultural-historical community; this is especially important geopolitically. Territory is an immanent part of any state, therefore its protection (or the protection of the state’s territorial integrity) means self-preservation. Without this no political or economic independence is possible. Any state concentrating on different values (ideological, moral, emotional, etc.) in its relations with the world outside is heading for defeat and dependence on other, stronger powers.

1 Report of the International Committee of Jurists entrusted by the Council of the League of Nations with the Task of Giving an Advisory Opinion upon the Legal Aspects of the Åland Question, League of Nations Off. J., Special Supp. No. 3, October 1920. Back to text

2 See: V. Oskanian, “Foreign Policy of Armenia,” available at [http://www.csis.org]. Back to text

3 See: Z. Mikhailov, “Baski doloy,” available at [http://www.dialogs.org.ua]. Back to text

4 Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Azerbaijan. Back to text