Ethnic cleansing of the Azerbaijani population in Armenian SSR

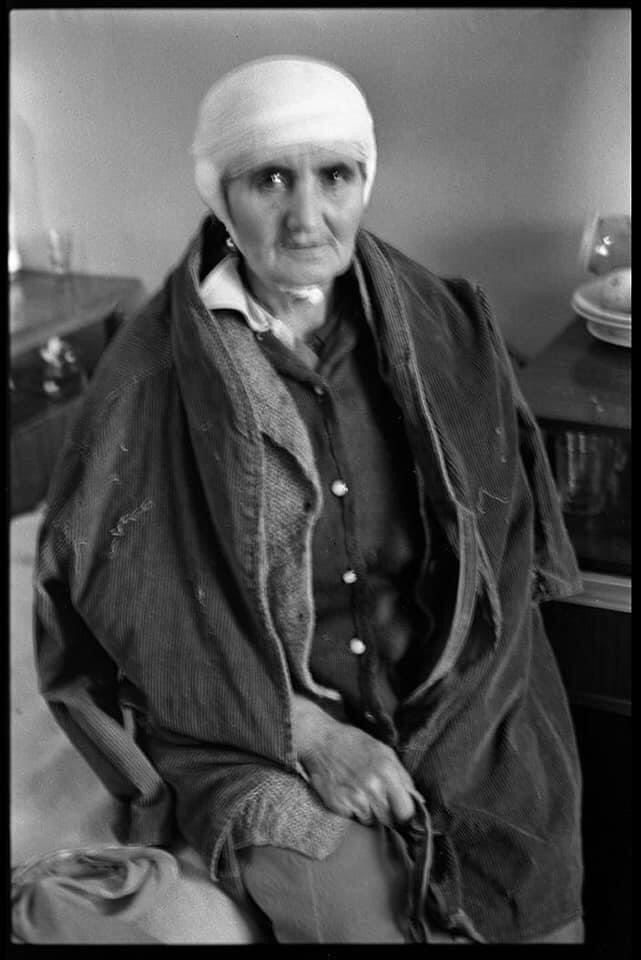

When the ethnic Azerbaijani citizens living in Kafan and Mehri districts of Armenian SSR were subject to brutal beatings and expulsion in November 1987, one could hardly imagine, the hatred towards Azerbaijanis would transform into a disturbing act of terror, culminating in Khojaly Massacre.

Foreshadowed by the public speech of Mikhail Gorbachev’s advisor Abel Aganbekyan in Paris on November 16, 1987 on annexation of Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan SSR to Armenian SSR, the nationalist circles in Armenia started to mobilize their efforts on the Republic Square in Yerevan. The ingredients had already been secretly prepped and a letter to Moscow with thousands of signatures of Armenians, petitioning an unconditional transfer of Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) of Azerbaijan SSR to Armenian SSR ensued. Note that the key word here is “unconditional” which means Armenians demanded an outright annexation of a part of the sovereign Azerbaijani territory of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia on grounds of population misbalance (76% Armenian versus 24% Azerbaijani) in favor of Armenians within the NKAO boundaries, whilst dismissing the entitlement, or its lack, thereof, for similar rights of 220 thousand Azerbaijanis densely populating Kafan, Mehri, Daralayez (Vayots Dzor), Basarkecher (Vardenis) districts to administrative political autonomy, let alone, unification with Azerbaijan proper.

And so the game plan played on. To avoid facing similar demands from the Azerbaijani minority in Armenian SSR, their complete and systematic expulsion from Armenia seemed the best option. November of 1987 delivered two railcars of first Azerbaijani refugees; January of next year – 4 buses. By the end of February, 1988, the number of the displaced was as high as 4 thousand. They were settled in urban areas such as Sumgait, Baku and Ganja. One may wonder as to why Azerbaijani refugees primarily expelled from rural areas of the aforementioned districts of Armenian SSR were placed in Azerbaijani cities instead of villages or settlements where they would have fit better.

The answer lies within the objective. The urban districts usually are subject to more visibility and are home to many more economic and socio-political interests at the disturbance of which a particular incident may escalate into a bigger event and subsequently spring back the reactive measures. In a village, where a population is limited to specific number, an interethnic violence would be contained to a minor local riot and would soon die off. In a city, much like Sumgait, Ganja and Baku, the unrest would likely start with a group of revengeful youth to grow into easily manipulated crowds dispersed in various districts of the city. They would harm people, break into shops, burn cars and clash with police, inevitably attracting attention of the pre-dispatched media, or simply designated people with video cameras.

And that is exactly what took place. Sumgait, as the most vivid example of manipulation of sensitive elements, would soon be assumed as the birthplace of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, because the cameras, usually in no hurry to capture “spontaneous” events in a less attractive industrial backyard such as Sumgait, were there to capture the images of “angry Azerbaijani mobs” turning the city upside down, right from the first hours of February 27, 1988. One should not be surprised that three days later, on March 2, 1988, these images were publicly broadcast in Switzerland and the United States, although the press containment policy of the Soviet Union never facilitated such an action in other regions of Soviet Union.

In the days following massacre of 131 civilians in the streets of Baku by the Soviet Army in January 1990, TV and radio stations were shut off, the information was suppressed to prevent any leaks associated with the massacre to an outside international press. Nonetheless, the images of the violence in Sumgait never described the roots of the violent disturbances, the fact that both Armenians and Azeris died as a result. Neither did they inform about the three ethnic Armenian gang leaders, the most infamous of them being Eduard Grigoryan who was caught in the act, charged, sued and convicted who disappeared into the thin air once he was transferred to a Moscow prison.

The result yielding from Sumgait events was that the ethnic cleansing of Azerbaijanis from Armenia which started in November of 1987 went absolutely unnoticed while the image of a victimized Armenians in Sumgait arose with the piece of video camera tape rolled over and over for Western audiences.

During the next few months following Sumgait events, the Communist leadership in Azerbaijan would continuously convince the Azerbaijani public of unbreakable bond of friendship between Azerbaijani and Armenian peoples. All the while, Azerbaijani populated areas in Armenian were being emptied by forcible evictions fueled by nationalist aspirations of Armenia which eventually transformed this Soviet republic into a mono-ethnic entity with no single representatives of Azerbaijani ethnicity left behind by early 1990. By contrast, not only did the ethnic Armenians remained a sizable minority within Azerbaijan, excluding its Karabakh region, but they were able to retain their status of a 30 thousand-strong minority to this day, in an independent Azerbaijan, primarily living in urban areas such as the capital Baku, Sumgait and surrounding settlements.

History of the demographic changes within the context of the Karabakh conflict is rather “fascinating”, in a sense that historical Azerbaijani lands within the present day Armenia, where Azerbaijanis retained the absolute majority, such as Irevan, Sharur-Daralayez, Surmaly, parts of Novo-Bayazit uyezds as recent as the beginning of the 20th century, were systematically emptied of Azeris by Russian imperial authorities followed by Soviet leadership with establishment of USSR. The largest recorded displacement of Azerbaijanis from their native homeland what is now southern and eastern Armenia, was realized in 1948-1953, as per two infamous decrees by Soviet Union’s Council of Ministers numbered 4063 and 754. As a result, more than 100 thousand Azerbaijanis were relocated from regions of Armenia to lowlands of Azerbaijan, thus emptying living space for incoming Armenians from diaspora, primarily from Lebanon and Syria.

Nevertheless, ethnic Azerbaijanis remained in big numbers and constituted the biggest ethnic minority in Armenia until the beginning of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in 1987. No socially and/or ethnically driven cultural rights were distinctly given and no autonomy was extended to Azeris, while Armenians enjoyed linguistic, cultural, social and more importantly, political governing rights within Azerbaijan. In the long run, it eventually contributed to illegitimate demands for an annexation of a part of a sovereign state to another.

With mobilized efforts to drive out all of the remaining Azerbaijani population of Armenia in late 1980’s, the Armenians sealed off the possible quest of Azerbaijani minority in Armenia for a cultural autonomy. What was left to do by the first quarter of 1990 was to play victim, force out the Azerbaijani population of Nagorno-Karabakh and unilaterally annex it to Armenia. The plan was realized with two effective instruments: terrorism throughout Azerbaijan outside of the conflict zone and massacres within the conflict zone.

The term “Armenian terrorism” came onto headlines in mid 1970’s when the terrorist organizations ASALA (Armenian Secret Army for Liberation of Armenia) and Justice Commandos for Armenian Genocide (JSAG), among many other smaller groups, have taken up a role of combating the Turkish civilians around the world for having allegedly committed “genocide” of Armenians in Anatolia in 1915. However, seeds of Armenian terrorism had been planted much earlier than 1915, when the Armenians of Turkey decided to form an ultranationalist Dashnaktsuitsuin (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) organization to establish a state in eastern Ottoman Empire at the end of the 19th century, at the behest of Russian imperial ambitions. From seizing a bank in Istanbul in 1896 to committing massacres of Azerbaijani civilians in Shusha during spring holidays in 1920, Dashnak militants have terrorized masses to the maximum extent. Decades later, a newer wave of Armenian terrorism in 1970’s-1980’s left dozens of Turkish civilians dead, subsiding to the minimal activity by 1985. With calls of Zori Balayan and Silva Kaputikian for annexation of Karabakh to Armenia, ultranationalist circles picked up the guns again. From Qazakh to Agdam, from Ganja to Baku, no Azerbaijani citizen was safe. Buses, trains, airplanes, subway traffic were subject to Armenian terrorist attacks. The last publicly known terrorist acts in Baku subway station were registered in Baku before and shortly after signing of ceasefire agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia in May 1994. One of the largest atrocities was shooting down of Azerbaijani relief airplane en route to Armenia to participate in search and rescue operations and help the Armenian earthquake victims in December 1988. All but one of 77 Azerbaijanis on board died.

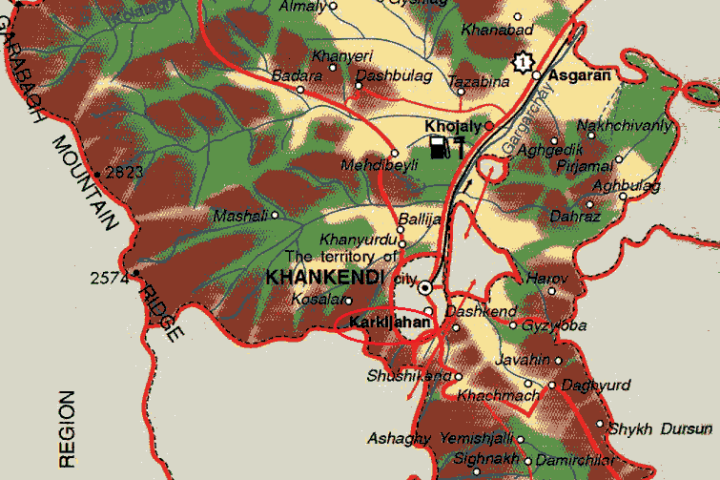

Ethnic cleansing of the Azerbaijani population in Nagorno-Karabakh

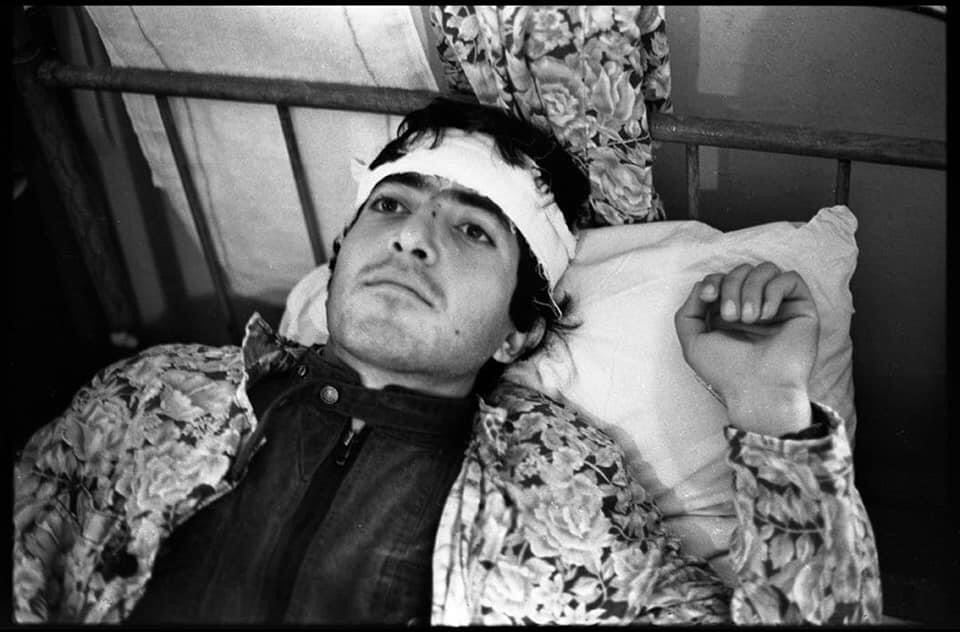

The second tool was terrorisation of local Azerbaijani population in Nagorno-Karabakh. Starting from late December 1989, Azerbaijanis were terrorized by public beatings, killings, grouped massacres throughout Karabakh, from Karkijahan suburb of Khankendi, Malibeyli, Gushchular to Garadaghly, all within a span of two months. Despite the villages of Malibeyli, Gushchular and Garadaghly rose in flames, the information on extermination of up to 140 civilians and complete ethnic cleansing of these villages was largely suppressed. The Azerbaijani residents of Karabakh still stood their ground. To break the confidence and intimidate the Azerbaijani population of the region, Armenians needed a debacle of bigger proportions which would put an end to hopes of peace and reconciliation. In the words of former Armenian president and then the commander of Armenian detachments Serzh Sargsyan: “Before Khojali, the Azerbaijanis thought that the Armenians were people who could not raise their hand against the civilian population. We were able to break that [stereotype]”[ref]Thomas de Waal, Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York and London, New York University Press, 2003, p. 172.[/ref]. He perfectly described the state of naïve trust and hope of the Azerbaijani party to the conflict which inadvertently fell victim to misguidance.

Starting with the headscarf of Khuraman Abbasova, a notable from Karabakh, thrown before the Azerbaijani crowd on February 22, 1988 near Askeran to prevent further bloodshed between Azerbaijani and Armenian people (It is an Azerbaijani tradition to respect an elderly woman and not step over her will once a “mother’s headscarf” is thrown before someone) after two Azeri youths, Ali Hajiyev and Bakhtiyar Guliyev, had fallen victims to Armenian bullets near Askeran, up until the underreported massacres in Garadaghly on February 17, 1992, Azerbaijanis were being convinced by the leadership that the friendship between Armenians and Azeris will live on. Khojaly proved otherwise. A rather unnoticed town of about 2,000 Azerbaijanis in early 1992, Khojaly was encircled by now Armenian occupied villages. In early months of that year, the town had already been living under blockade for several months in a row. The only communication to the town was by helicopter, delivering food and medical supplies. That was history by end of January, when the last helicopter with civilians on board was shot down by Armenian grenade launcher near Shusha. Hungry, cold, ignored and unprotected, Khojaly was enduring its last days.

Should the Armenians have kept a blockade alive for a few more weeks, the Azerbaijani residents would most likely have no choice but to either surrender or leave the town altogether.

However, the plan envisioned by Armenian army was not just to seize the town, but to subdue the Azerbaijani trust and break the promise of reconciliation in Karabakh. The intent was clear: occupy, exterminate and expose. The plan was to be enforced by several Armenian guerilla detachments, 366th regiment of the Russian army headed by Armenian officers and the missionaries.

Enter Monte Melkonian, the infamous terrorist who planned and executed murders of Turkish diplomats in Europe, spent time in French prisons and is now the highly glorified hero of Armenia. Melkonian had been responsible for massacring Azerbaijani civilians in Garadaghly and Agdaban villages in 1992. In the words of his brother Markar Melkonian, who described his militant career in his book “My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia”, Khojaly for Monte was an “act of revenge”. It was a good opportunity for extermination of enemy civilians, whom members of Arabo and Aramo detachments stabbed to death.

Unlike other genocides of 1990s, such as one in Srebrenica, where 8 thousand Bosnian men of different age were executed by firing squads to diminish future Bosnian fighting capabilities, Khojaly where 613 civilians (among them 106 women, 83 children, 79 elderly) were massacred, was an atrocious act, vandalism and inhuman behavior. What really distinguished Khojaly Massacre was the derision, humiliation, tortures and rapes of the victims. Children were killed in front of their parents. Parents were tortured before the eyes of their children. Women were publicly raped. Eyes of the already diseased civilians were gauged out, tongues cut off, breasts chopped off, arms and legs broken, bodies decapitated. Not only was it a physical atrocity but also a psychological calamity. One Azeri woman from a group of fleeing civilians had to suffocate her infant child when they hid in the woods so that the Armenian militants following them would not hear the cries of the baby.

By the time Azerbaijani cameraman Chingiz Mustafayev and international journalists made their dangerous flight into the kill zone, the killing spree had ended. Only the soothing wind was telling the story of unimaginable proportions about violence inflicted on unarmed civilians. Dispersed throughout the hills, the bodies of children, women, and elderly lay unmoved, for one simple reason. They were Azerbaijani Turks. The pictures shot by Mustafayev profoundly changed what the conflict was really about. In the film, chopper sounds and shots from the Armenian guns on the horizon were the only background to crying Azerbaijani men who almost lost conscience when seeing the despicable act of terror committed by Armenian militants. Khojaly massacre, as well documented as it is, has become an inalienable part of Armenian military history. It serves as a well-deserved opprobrium of continued warfare waged on Azerbaijani and Turkish civilians for more than a century.

Perpetrators of Khojaly Massacre have not been prosecuted yet. Some were killed by Azerbaijani soldiers of Ganja regiment by Hasangaya village of Aghdara in summer of 1992; some have returned to Armenia to become heroes; some took executive positions such as the President of Armenia, Serzh Sarkissian and Defense minister Seyran Ohanian. In 2012, the Prosecutor’s office of Azerbaijan Republic disclosed the list of main actors charged with the Khojaly Massacre.

Following terror attacks on the Twin towers in Manhattan on September 11, President George W. Bush stated, “whether we bring our enemies to justice or bring justice to our enemies, justice will be done.” Mass murder in New York or mass murder in Khojaly, justice awaits them all.

Yusif Babanly is the co-founder and secretary of the US Azeris Network (USAN) and a member of the board of directors of Azerbaijani American Council.

Source: TurkishWeekly.net