The Aland Islands are very often cited as another example of a conflict of this kind where the ethnic conflict did not result in bloodshed but was resolved by way of finding a special status within the limits of self-determination.

The Alands is an archipelago of 8,000 islets situated in the Baltic Sea. The population of these islets were part of the Swedish Kingdom until 1808, and spoke Swedish from time immemorial. At that time Norway and Finland were both part of Sweden. As a result of the 1808-1809 war, Sweden was forced to cede Finland and the Alands to Russia. After a defeat in the Crimean War in 1856, Russia had to recognize the Alands as a de-militarized zone. At the beginning of the 20th century, Norway peacefully seceded from Sweden on the basis of a referendum. In 1917, Russia recognized the independence of Finland. At that time, the Swedish population of the Alands expressed their desire to reunite with their ancient homeland, Sweden, and sent the King of Sweden a petition signed by the entire adult population of the islands. In December 1917, Finland voiced its opposition to the desire of the Alands population and suggested that the terms of self-determination should be coordinated with it. The Alands islanders rejected these suggestions. A conflict was growing, but neither side took up arms.

In 1921, the League of Nations passed a resolution: the Aland islands, neutral and demilitarized, were declared to be a territory belonging to Finland. Finland was given the responsibility of guaranteeing to the population of the islands the preservation of the Swedish language, customs and traditions and the development of Swedish culture.

Sweden and Finland concluded a Treaty according to which the population of the Alands gained the right to preserve their language, culture and traditions and thus the threat of assimilation was removed. Sweden received guarantees of security for the Swedish population of the islands and the right of unimpeded communication with them.

According to the Law of 1922 on self-government, the local parliament-Lagting is entitled to adopt laws on the internal affairs of the islands and on the budget. The Lagting appoints the government. In accordance with the Constitution of Finland, the laws on self-government can be amended by the Parliament of Finland only with the consent of the Lagting of the Alands. The law-making powers of the Lagting are defined in the following spheres: education and culture; public health; economy; transport; communal services; police; postal services; radio and television. In these spheres, the Alands hold the power of a sovereign state. The rest of the legislative powers are the prerogative of Finland: foreign policy; the bulk of the civil code; courts and criminal law; customs and money circulation.

To defend the interests of the Aland population, one deputy from the archipelago is elected to the Parliament of Finland. With the consent of the Lagting, the president of Finland appoints the governor of the islands. The powers of the governor are as follows: to head the Council of representatives of the Aland Islands (formed on parity principles); to open and close sessions of the Lagting.

In the economic sphere, relations are built according to the following pattern: the government of Finland levies taxes, collects customs and other levies on the islands the same way it does in the rest of the country. The expenses on the archipelago are covered from the state budget. The archipelago recieves a proportion of state revenues after the deduction of its share for state debt repayment. It is up to the Lagting to decide how to distribute the remaining sum according to budget items.

The laws adopted by the Lagting are sent to the President of Finland who has the right of veto. This veto can be exercised only in two cases: if the Parliament of the islands exceeds its powers or if the adopted law contains a threat to the internal and external security of Finland.

The right to live on the islands is equivalent to the right to citizenship. Every child born on the islands has that right on condition that one of his/her parents is a citizen of the Alands. The islanders are simultaneously citizens of Finland. The right of Aland citizenship is granted to any citizen of Finland who has moved to the archipelago and has lived there for five years on the condition that he speaks Swedish.

Restrictions on the rights for foreigners regarding the ownership of real estate are explained by the aspiration to secure land for the residents of the Alands. A resident of an island, who has lived for five years outside the Alands, loses his citizenship. A citizen of the Alands is exempted from the duty of serving in the Finnish Army. It is also forbidden to station troops and build fortifications on the islands.

The Alanders may directly cooperate with Scandinavian countries. They also take part in the work of the Northern Council.

Foreign policy is the prerogative of the Government and Parliament of Finland. But if Finland signs an international treaty that affects the internal affairs of the Alands, then the implementation of the treaty should be coordinated with the Lagting.

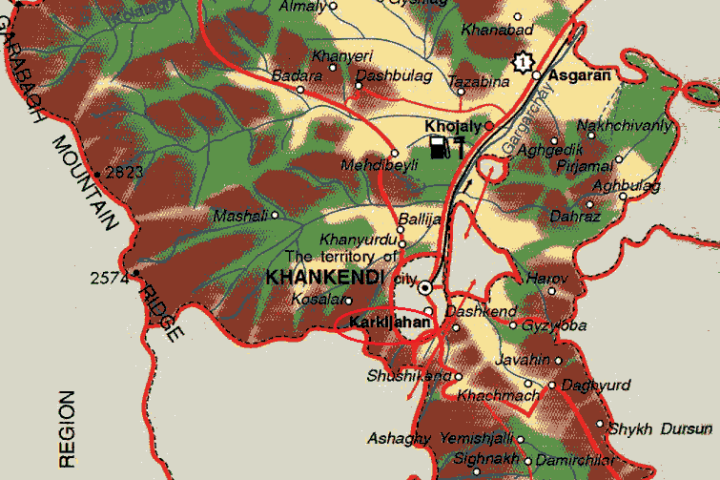

The Alands model was proposed by international intermediaries as a possible future model for relations between NK and the Azerbaijan Republic. A symposium of Azeri, Armenian and NK parliamentarians was held on the Aland Islands on December 21-22, 1993, upon the initiative of the CIS Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, the Federal Assembly and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. During the symposium, details of the model16were presented. However, the authorities of NK consider that the Alands model fails to take into consideration“the historical basis and psychological consequences of the Karabakh-Azeri conflict and of the war fought for NK’s de facto independence from the Azerbaijan Republic”. Besides, according to the firm conviction of the Armenian and the Karabakh sides, the Alands model was inapplicable to the conditions of the South Caucasus also for the reason that the question of the status of the mentioned archipelago in the 1920s was not resolved separately, but within the framework of the general issue – the so-called “Sweden problem” in Finland. The Swedes were able to get equal rights not only in the Alands but also in Finland as a whole where the Swedish language is the second state language.

The possible schemes of principle for the solution of the problem (part 3)