This article looks at issues associated with the establishment of the Azerbaijan-Armenia border in 1920-1922. Based on extensive facts, it tries to shed light on the reasons for the territorial disputes between Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Introduction

The borders of today’s sovereign Caucasian states were mainly formed between 1918 and 1921. The question of what territory belonged to each of the newly formed states was extremely urgent from the very moment Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia declared their independence in May 1918. The territorial disputes of that period arose from the lack of correspondence between the administrative-territorial structure of the territory and the ethnic composition of the population in the prerevolutionary period. The provinces of the South Caucasian region had quite a number of districts with an ethnically mixed population. Attempts to demarcate the region in keeping with national characteristics gave rise to territorial conflicts.

This caused the political confrontation between Armenia and Azerbaijan that characterized the relations between the two countries right up to the establishment of Soviet hegemony in the region. Soviet Russia’s policy regarding the disputed territories changed depending on its interests. But it was the claims of the Armenian side that were most frequently satisfied.

However, the establishment of Soviet power in the region did not stop, rather it intensified Armenia’s territorial claims on Azerbaijan even more. And all of this made the establishment of borders between the two Soviet republics at the beginning of the 1920s extremely urgent.

Neither this issue, nor the Soviet Russia’s role in the process, has been the subject of a separate study in either the Soviet or the post-Soviet period, rather these topics were studied in the overall context of the political events in the Caucasus.

The State of the Azerbaijan-Armenia Border on the Eve of Sovietization of Azerbaijan

The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) covered an area of 113,895.97 sq. km, 97,297.67 sq. km of which were not the target of any claims. It included the following territories: the Baku province (39,075.15 sq. km), the Ganja province (44,371.29 sq. km), the Zakataly district (3,992.54 sq. km), and part of the Irevan province (9,858.69 sq. km, which included the 1st and 2nd police precincts of the Sharur-Daralaiaz district; the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th police precincts of the Nakhchivan district; and the 1st and 2nd police precincts of the Novobaiazet district). The republic’s northern border passed along the River Samur and the Greater Caucasus Range. In the west, the border with Georgia coincided, apart from a small section, with today’s border. The Azerbaijan-Armenia border passed along the former administrative border of the Surmalu district to the Araks River, through the Irevan district through the village of Agamaly, Bash-Giarny, and Imirzin, and on along the border of the Novobaiazet and Sharur-Daralaiaz districts, turning later to cross Geicha (Sevan) Lake and dividing it in two. So the village of Chubukhly remained under Armenia’s jurisdiction, while the rest of the eastern shore of the lake was part of Azerbaijan.1 On the basis of this border, the whole of the Ganja province and all the districts—the Surmalu, Nakhchivan, and Sharur-Daralaiaz—of the Irevan province, as well as the southern part of the Irevan district with the villages of Kamarlu, Beiuk-Vedi, and Davalu and the eastern part of the Novobaiazet district belonged to Azerbaijan. On the eve of the April revolution of 1920, Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan belonged to the Azerbaijan Republic.

Gazakh, Karabakh, Nakhchivan, and Zangezur belonged to the territories to which Armenia was making claims.

During the years of independence, the leadership of the ADR was forced to give some of its historical territory to Armenia. During the Batumi Conference (11 May-4 June, 1918), talks were held between representatives of Azerbaijan and Armenia about the borders between the two countries. The report of delegation member of the Transcaucasian Muslim Council N. Usubbekov at a special sitting of former members of the Transcaucasian Seim of 27 May, 1918 noted that “the main guarantee of the Transcaucasus’ prosperity, according to the Turkish delegation, is solidarity and unification of the Transcaucasian nationalities, which will require Azerbaijan transferring some territory to the Armenians.”2 In this way, Turkey was in favor of creating an Armenian state in the Transcaucasus and advised Azerbaijan to give up some of its territories. On 29 May, at a sitting of the Muslim National Council in Tiflis, the results of the talks between the representatives of the Council and the representatives of the Armenian National Council on this issue were discussed. In his speech, member of the Muslim National Council F. Khoisky said that in order to form an Armenian federation, they needed a political center and, after Alexandropol (Gumri.—S.M.) had gone to Turkey, this role could only be filled by Irevan, so transferring Irevan to the Armenians was inevitable. In their speeches, Council members Kh. Khasmamedov, M. Jafarov, M. Magerramov, and others called cession of Irevan to the Armenians “a historical necessity and inevitable evil.” During the voting, 16 votes of the total number of 28 were in favor of transferring Irevan, and the Council members were unanimous in their decision to form a confederation with the Armenians.3

So the National Council, under pressure from Turkey and “wishing to help a neighboring state that had declared its independence,” made such an important decision regarding the transfer of a city to the Armenians. However, as early as 1 June, 1918, at a sitting of the Muslim National Council in Tiflis, a protest was declared signed by members of the National Council (G. Seidov, B. Rzaev, and N. Narimanbekov) against cession of Irevan to the Armenian Republic. But the National Council resolved, without discussion, that the protest be appended to the protocol.4 The protest was not accepted, since at the talks between representatives of Azerbaijan and Armenia in Batumi, an agreement was reached on the following issues: Azerbaijan agrees to create an Armenian state within the limits of the Alexandropol province; the city of Irevan shall be transferred to Armenia on the condition that the Armenians withdraw their claims to part of the Elizavetpol province, that is, to the mountainous part of Karabakh.5From the letter of Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Azerbaijan Republic F. Khoisky, sent on 31 July, 1918 to Chairman of the Azerbaijan delegation in Istanbul M. Rasulzade, it became clear that, along with Irevan, part of the Gazakh district was also transferred to the Armenian Republic at the Batumi Conference.6

But Irevan was transferred to Armenia temporarily. In January 1919, representative of Azerbaijan to Georgia M. Jafarov noted in a conversation on the borders of Azerbaijan with English General Beach that Irevan was being transferred to the Armenians temporarily, until the Turks evacuated Alexandropol.7 But even this transfer could not prevent further aggravation of the relations between the two republics.

The Role of Soviet Russia in Settling the Territorial Disputes between Azerbaijan and Armenia

Diplomatic correspondence between Soviet Azerbaijan and the Ararat (Armenian.—S.M.) Republic regarding Karabakh and Zangezur began from the very first days Bolshevik power was established in Azerbaijan. Moscow, in turn, after agreeing to Armenia’s proposal, took on the role of intermediary between these two republics. After declaring several territories disputed (Nakhchivan, Zangezur, and Karabakh), the Bolsheviks announced that they would be occupied by Red Army troops.8 But the Bolsheviks could not make up their minds about which republic certain territories belonged to and more often than not came down on the side of the Armenians. Many documents provide evidence of this. In the first days after Sovietization of Azerbaijan, Grigori Ordzhonikidze sent a telegram to People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Soviet Russia Georgi Chicherin in which he wrote that the territories of Zangezur and Karabakh must remain part of Azerbaijan in order to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Ottomans.9 In one of his notes to Vladimir Lenin, Iosif Stalin, and Georgi Chicherin, Grigori Ordzhonikidze wrote that the Armenian delegation would agree to Karabakh and Zangezur immediately being joined to Azerbaijan if Azerbaijan relinquished the Sharur-Daralaiaz district and the Nakhchivan district, and that they would raise this question in Baku when talking to Nariman Narimanov.

On 9 May, 1920, Azerbaijan asked Armenia to begin talks on the border issues no later than 15 May, 1920. Armenia declined this request, since it was still hoping to receive help from the great powers in the border question. And help this time came from Soviet Russia. On 15 May, 1920, Deputy People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the R.S.F.S.R. Lev Karakhan sent a telegram to People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan Mirza Huseinov. It said that the Armenian government had asked the Russian government to intermediate between Azerbaijan and Armenia and that the Soviet government, consenting to do this, had decided to occupy the areas that Azerbaijan and Armenia were disputing with Red Army contingents.10

Grigori Ordzhonikidze’s telegram to Georgi Chicherin of 19 June, 1920 is notable, in which he said that “Azerbaijan is making claims to Karabakh, Zangezur, and the Nakhchivan and Sharur-Daralaiaz districts. Soviet power has been declared in Karabakh and Zangezur, and the above-mentioned territories consider themselves to be part of the Azerbaijan Soviet Republic. Nakhchivan has been in the control of Azeri Muslim insurgents for several months now. I do not have any information about the Sharur-Daralaiaz district.”11 In his letter to Lenin, Chicherin assured: “The Azerbaijan government has made claims to Karabakh, Zangezur, and the Sharur-Daralaiaz district along with Nakhchivan, Ordubad, and Julfa. Most of these areas are in fact under the control of the Armenian Republic.”12 But Karabakh and Zangezur could in fact not have been under Armenian control at that time, since in compliance with the Decree on District Councils of the National Economy of 28 June, 1920, the borders of the districts of Azerbaijan had been determined, in particular, the Zangezur, Jevanshir, and Shusha districts were included in the Karabakh district.13 So, according to this document, in June 1920, Karabakh and Zangezur were still part of the Azerbaijan Republic.

At this time, Sergei Kirov (member of the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks).—S.M.) sent a letter from the Caucasus to Chicherin on the state of affairs in Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, in which he wrote: “I have had repeated meetings with him (Mirza Huseinov.—S.M.) and with the Armenian representatives… All of this has resulted in only one thing—Azerbaijan’s willingness to transfer the Sharur-Daralaiaz district to Armenia; it goes without saying that Azerbaijan considers all the others, that is, the Nakhchivan district, Ordubad, Julfa, Zangezur, and Karabakh, to belong to it. In turn, the Armenian representatives are making categorical claims to these areas. Azerbaijan’s main reasoning is that under the ADR government these regions belonged to Azerbaijan and if they are now transferred, it will discredit Soviet power not only in the eyes of Azerbaijan, but also of Persia and Turkey. The representatives of Armenia and Azerbaijan were planning to hold a peace conference in the near future to resolve all the disputed issues, but neither side is confident that they can reach any kind of agreement at this conference. So hopeless is this issue here. I have already told you that the only solution is to have Moscow make a resolute decision, only its authority can decide the matter.”14

In a telegram of 14 July, 1920 to Chicherin, Ordzhonikidze and Russian representative to Armenia Legran wrote: “We believe that the question must be decided in a way that could partially satisfy Azerbaijan: join Karabakh entirely and unconditionally to Azerbaijan. Zangezur is declared disputed, while the other areas (Nakhchivan, Sharur-Daralaiaz, and Ordubad) will remain under Armenian control.15

This same policy was set forth in a resolution of a session of the Central Committee Bureau of the Azerbaijan Communist Party (Bolsheviks) held on 15 July, 1920, where the question of peace with Armenia was discussed: “1. Karabakh and Zangezur should be joined to Azerbaijan. 2. Nakhchivan and the other districts should be relinquished, it should be proposed that they be occupied by Russian troops.”16

Karabakh, Nakhchivan, and Zangezur as Bargaining Chips in the Sovietization of Armenia

On 10 August, 1920, a preliminary agreement was signed in Irevan between the R.S.F.S.R. and Ararat Republic on cessation of hostilities, according to which “R.S.F.S.R. troops shall occupy the disputed areas of Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan” until the borders between Azerbaijan and Armenia are determined.17 Azerbaijan was against declaring the territories of Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan disputed.

After signing the above-mentioned agreement with the R.S.F.S.R., in response to the repeated requests by Azerbaijan to convene a conference for settling all the disputed issues, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Agajanian sent the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan a telegram that read as follows: “According to the preliminary agreement entered between representatives of the government of Armenia and authorized representative of the R.S.F.S.R. Legran of 10 August, 1920, the territorial disputes between Armenia and Azerbaijan should be settled on principles set forth in a peace treaty to be entered between R.S.F.S.R. and the Republic of Armenia in the nearest future. In view of the stated and in response to your proposal to convene an Armenia-Azerbaijan conference on 20 August, I inform you that my government considers convening such a conference before entering a final agreement with the R.S.F.S.R. to be premature.” The Armenian representatives said that the Armenia-Azerbaijan border would be established in keeping with the agreement of 10 August, 1920 between Russia and Armenia.18 According to the new agreement of 28 October, 1920 on regulation of relations with Russia, Armenia said it would reject its claims to Karabakh providing that it was transferred Zangezur and Nakhchivan and issued a loan of 2.5 million golden rubles.19

In reality, after Sovietizing Azerbaijan and taking advantage of the territorial issue, Soviet Russia was trying to draw other Caucasian states onto its side, in this case Armenia. This is clear from Stalin’s words, who on 9 November, 1920 gave a speech in Baku at a joint session of the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Central Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Revolutionary Committee of the Azerbaijan S.S.R., and Baku Party Committee on immediate party and Soviet work in Azerbaijan. Stalin gave the following response to one of the written questions: “In Zangezur, there is an uprising (initiated by members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Party). We are fighting them. If they want to know who (disputed) Zangezur and Nakhchivan should belong to, they cannot be given to the current government of Armenia (ARF), if the government is Soviet, perhaps it will be possible.”20

At the end of the war with Armenia, Turkey signed a peace treaty in Alexandropol on 2 December, 1920. According to this treaty, Nakhchivan, Sharur, and Shakhtakhty were declared to be “temporarily” under the protection of Turkey. To all intents and purposes, Turkey’s protectorate was also established over the territory that formally remained in Armenian jurisdiction.21

On 2 December, Authorized Representative of the R.S.F.S.R. to Armenia Legran signed an agreement with representatives of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation on declaring Armenia a Soviet Republic. The territory of Soviet Armenia was defined as follows: the Irevan district, part of the Kars region, the Zangezur district, part of the Gazakh district, and those parts of the Tiflis province that were under Armenian jurisdiction before 8 September, 1920.22In so doing, Armenia signed an agreement with Turkey and Soviet Russia at the same time, hoping to receive help from the latter. But the residents of Nakhchivan protested against the above-mentioned decisions. As early as 28 July, 1920, the Nakhchivan S.S.R. was created there. The Revolutionary Committee of Nakhchivan declared that Nakhchivan was an integral part of Azerbaijan. And so the Revolutionary Committee of Armenia was forced to recognize Nakhchivan as an independent Soviet Republic on 28 December, 1920. In January 1921, a population poll was conducted there in which representatives of Turkey, the R.S.F.S.R., Azerbaijan, and Armenia participated. Ninety percent of the population of Nakhchivan said they wanted to remain a part of Azerbaijan.23 The Ankara government agreed to withdraw its troops from Nakhchivan only if Russia recognized this region as an integral part of Azerbaijan. In this way, resistance of the local residents and Turkey’s position on the question of who Nakhchivan belonged to decided the fate of this territory. The status of the Nakhchivan territory was ultimately decided by the Moscow Agreement signed on 16 March, 1921 between the R.S.F.S.R. and Turkey and the Kars Treaty signed with the participation of the R.S.F.S.R. on 13 October, 1921 among the Azerbaijan S.S.R., Armenian S.S.R., and Georgian S.S.R., on the one side, and Turkey, on the other. Article 3 of the Moscow Agreement defined the status and borders of the Nakhchivan province: “Both of the negotiating parties agree that the Nakhchivan region within the borders set forth in Appendix 1(c) to this agreement forms an autonomous territory under the protectorate of Azerbaijan, providing that Azerbaijan does not concede its protectorate to a third country.24 But in reality, Soviet Armenia ignored the articles of the Moscow Agreement regarding the Nakhchivan territory. A telegram of 13 July, 1921 from the People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the A.S.S.R. Mirza Huseinov to Grigori Ordzhonikidze requested that measures be taken to recall the Armenian representatives from the Nakhchivan territory, since their actions could give rise to “new attempts [by Turkey] to make claims to the Nakhchivan territory under the pretense of non-fulfillment of the Moscow Agreement.”25[25]

The decision of the Politburo and Organizing Bureau of the Azerbaijan Communist Party (Bolsheviks) regarding transfer of Zangezur to Armenia was executed as early as 1921. And this was despite the fact that the Muslim population of the territory was against joining Armenia. A report by extraordinary commissar of Karabakh and Zangezur Sh. Makhmudbekov of 24 December, 1920 says that “representatives of Lowland Zangezur, consisting of 4 sections, [came to see him] and announced their categorical decision to remain under the administration of Azerbaijan Soviet power, and if their petition was not met, they would ask to be shown where they could move.”

Meanwhile, in his report at the First Congress of Soviets of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. of 9 May, 1921, Mirza Huseinov talked about Zangezur as Armenian territory.26 According to the data of Armenian authors, on 20 July, 1921, the Council of People’s Commissars approved a decree on the administrative division of Armenia, according to which Soviet Armenia was divided into eight districts—Irevan, Alexandropol, Echmiadzin, Idzhevan, Karaklis, Nor-Baiazet, Lori-Pambak, and Daralaiaz. Later the Zangezur district was established.27 In this way, the western part of Zangezur was taken from Azerbaijan by a decision of the central government and joined to Armenia.

The question of Nagorno-Karabakh was difficult to resolve. After the Sovietization of Georgia, on 2 May, 1921, a decision was made at a plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) about creating a commission from representatives of the Transcaucasian republics under the chairmanship of Sergei Kirov to define the borders between the Soviet republics of the Caucasus. The results were to be submitted for approval at the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau. Even before the session of this commission began, it was noted in a resolution of the Caucasian Bureau of 3 June, 1921 that the government of Soviet Armenia should indicate in its declaration that Nagorno-Karabakh belonged to Armenia.

On 12 June, 1921, the Armenian government, supposedly on the basis of an agreement with Azerbaijan, issued a decree on Nagorno-Karabakh being joined to Armenia. But this statement by Armenia aroused sharp protest in Azerbaijan. Sessions of the commission under Kirov’s chairmanship with Svanidze, Todria (from Georgia), Huseinov, Gajinsky, Rasulzade (from Azerbaijan), and Bekzadian (from Armenia) in attendance were held in Tiflis between 25 and 27 June, 1921. At the very first session, Bekzadian asked the commission members to keep in mind the czarist government’s unfair administrative division of the Transcaucasus and the extremely difficult position of Soviet Armenia and, “for the sake of general solidarity and the ultimate establishment of the most genuine and friendly relations, to make certain territorial concessions, whereby in districts densely populated by Armenians.” These concessions related to the Akhalkalaki district, to the Lori neutral zone and to Nagorno-Karabakh.

Bekzadian also noted that in Moscow, in May, Stalin fully shared this viewpoint in a conversation with him and Miasnikov. But the representatives of Georgia and Azerbaijan, proceeding from the political considerations of a struggle against internal nationalistic counterrevolution, put forward counter proposals about the impermissibility of any territorial trimmings. They were also supported by Kirov.28 Thus the question of territorial demarcation was not resolved favorably for Armenia, and so Armenian representative Bekzadian took it to the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), asking it to make a decision.

On the morning of 26 June, 1921, Ordzhonikidze and Kirov sent the following urgent telegram from Tiflis to Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissar of the A.S.S.R. Nariman Narimanov: “…Please convene an urgent Politburo and People’s Commissar Council meeting and settle the question of Karabakh so that tomorrow, 27 June, the talks can be finished. If you are interested in our opinion, here it is: in the interest of finally defusing all tension and establishing genuinely friendly relations, the following principle should be used when settling the Nagorno-Karabakh question: not one Armenian village should be joined to Azerbaijan, just as not one Muslim village should be joined to Armenia.”29

On 27 June, 1921, at a session of the Politburo and Organizing Bureau of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party (Bolsheviks), when discussing the question of borders between Azerbaijan and Armenia, it was resolved with respect to the work of the commission in Tiflis that: “On the whole, the Politburo and Organizing Bureau consider the question of Nagorno-Karabakh in the way it has been raised by comrade Bekzadian to be unacceptable. Due to Nagorno-Karabakh’s indisputable economic pull toward Azerbaijan, the question should be resolved in that vein. So the proposal to separate areas with Armenian and Azeri populations and give them to Armenia and Azerbaijan, respectively, is also considered unacceptable from the viewpoint of administrative and economic expediency.”30 The same day, Nariman Narimanov sent a telegram to Ordzhonikidze requesting that Extraordinary Representative of Armenia Muravian be recalled from Karabakh. The telegram pointed out that the question of Karabakh had not ultimately been settled and the presence of an Armenian representative there was a political and tactical mistake.31

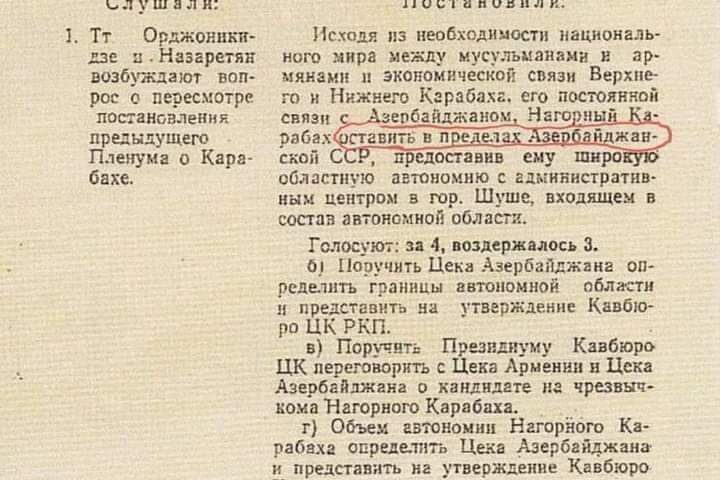

A plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was held from 2 to 7 July, 1921. On 4 July, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh was discussed at an evening sitting of the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau. The Caucasian Bureau issued the following resolution: “Nagorno-Karabakh shall be made part of the Armenian S.S.R. and a referendum shall be held only in Nagorno-Karabakh.” But after Mr. Narimanov’s statement that “due to the importance of the Karabakh question for Azerbaijan, ” he believed “it necessary to take it to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) for a final decision,” the Caucasian Bureau agreed with this opinion. On 5 July, at the next session of the Caucasian Bureau, the decision to transfer the question to Moscow, to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), was cancelled and a new resolution was adopted, which said: “Based on the need for national peace between Muslims and Armenians and for economic relations between Upper and Lower Karabakh, as well as its permanent relations with Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh shall remain within the boundaries of the Azerbaijan S.S.R., granting it broad regional autonomy with its administrative center in the town of Shusha.” Moreover, the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Azerbaijan was instructed to define the borders of the autonomous region and submit its decision to the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) for approval.32

Establishment of the State Border between Azerbaijan and Armenia

On 15 August, 1921, after hearing the border question relating to the Soviet republics of the Transcaucasus, the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau resolved that the chairmen of the Council of People’s Commissars and the Revolutionary Committees of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia should be asked to sign an agreement defining the borders between the three republics and a commission made up of Lukashin, Huseinov, Svanidze, and Orakhelashvili should be instructed to draw up a draft of the agreement.33 This general agreement among the governments of the Caucasian republics was never signed. And the territorial question remained urgent throughout the 1920s-1930s.

At a session of the Presidium of the Azerbaijan Central Executive Committee of 15 April, 1922, it was resolved: “In order to settle border disputes between the Azerbaijan S.S.R. and the Armenian S.S.R., two mixed commissions shall be formed: one for the Gazakh and the other for the Karabakh district.” Chairman of the Azerbaijan Central Executive Committee Agamaly ogly sent this resolution to the Union Council with a request to inform the Central Executive Committee of Armenia about this decision. Having been informed of this, the Central Executive Committee of Armenia reported the following in a telegram of 27 April, 1922: “By a resolution of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of Armenia, two commissions have been formed to settle the disputed border issues between the Delizhan and Kazakh districts … We would also like to appoint representatives of the Union Council as chairmen of these mixed commissions, for which we ask your consent.”34 At a sitting of the Union Council of 8 May, 1922, it was resolved: “To form a special commission from the Chairmen of the Union Council and the Central Executive Committees of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. and Armenian S.S.R. to clarify disputes in the border region between the aforesaid republics.”35

An order of the Extraordinary Committee for Transcaucasia of 22 August, 1922 abolished all the border posts in the territory, declared all internal borders open, and regarded the borders with Turkey and Persia as the external borders.36 This order was supposed to alleviate the border disputes among the Caucasian republics. But despite the above-mentioned decision, border disputes continued to exist. The following note was sent to Government Chairman of Armenia Dovlatov on 30 September, 1922 from representative of the Azerbaijan People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs Shirvani: “According to the statement of the Main Police Administration of the Azerbaijan Republic, residents of the Khaladuz and Darzhlin communities are being oppressed by the authorities of the border Kafan area of the Zangezur district in order to make them recognize the government of the Armenian Republic. Due to the fact they are part of the Kubatlu district, which means they are administratively subordinate to the Government of the A.S.S.R., I am asking the Government of the Armenian S.S.R., in your person, to compel the border authorities to cease their illegal acts.”37

At a sitting of the Presidium of the Transcaucasian Territorial Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) held on 30 October, 1922, the question was discussed of settling border disputes on the Armenia-Azerbaijan (in the area of the Tauz, Gazakh, and Karavansarai districts) and the Georgia-Azerbaijan (Signakhi district) borders. The following resolution was made on this issue: “For final settlement of border disputes, it is resolved to designate a commission of the Transcaucasian Territorial Committee comprised of comrades G. Ordzhonikidze, N. Narimanov, and A. Miasnikov. The Transcaucasian Territorial Committee states that the resolutions of the Presidium of the Union Council of 20 May of this year on settlement of land disputes between the villages of Muslim Tatly and Armenian Tatlu, and the villages of Chakhmakhli and Lalakend … have still not been executed. This is giving rise to several local disagreements, which are threatening to become acute. The Transcaucasian Territorial Committee believes it possible to establish the same land management and forest use procedure that existed locally before the formation of separate republics, whereby the question could be resolved by changing the state borders, meaning transferring some of the Armenian villages to Azerbaijan, or by acquiring Armenia’s full guarantee that from now on Azeri farmers can enjoy unhindered use of the disputed lands.”38 But not one assembly was convened in the period we are studying.

According to an explanatory note to the map of state borders of the Azerbaijan S.S.R. of 24 October, 1922, the state border between Azerbaijan and Armenia was not registered by any border agreements, but was established according to actual territorial possession after the agricultural census in the Azerbaijan S.S.R. at the end of 1921 carried out by the Central Statistics Board. Whereby the borderline drawn on the map was not plotted in keeping with the attribute “sequence of natural topographical points,” but passed along the line of several villages, the residents of which were administratively and actually subordinate to the A.S.S.R., and so its description could not be underpinned with any geographical names.39

In Lieu of a Conclusion

Sovietization brought about the loss of part of Azerbaijan’s historical land. Northern Azerbaijan covered an area of 113,895.97 sq. km by the beginning of 1920, while after Sovietization it lost 29,338.2 sq. km, 12,779.6 sq. km of which were transferred to Armenia. As a result of the policy conducted by Soviet Russia, the territory of Armenia, which covered an area 9.2 thousand sq. km at the time the republic was formed in 1918, increased to 28.1 thousand sq. km between 1920 and 1922.40 By the time of 1926 census was carried out, the territory of Armenia amounted to 30.24 thousand sq. km.41 That is, during the years of Soviet power, Azerbaijan lost 12,000 sq. km of its territory. Armenia was “given” the following districts: Gafan, Gorus, Sisian, and Meghri, which constitute approximately 4,504.5 sq. km.42 And it was only the presence of Turkish troops in Nakhchivan and the resistance of the local population that prevented Armenia from annexing this district too.

Seizure of part of historical Karabakh, Zangezur, from Azerbaijan was just the beginning of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Party’s plans, which were consistently put into practice for decades and were aimed at annexation by Armenia of more and more of Azerbaijan’s lands. One of the party’s leaders, Ov. Kachaznuni, regarded Soviet Russia as Armenia’s only bastion. In 1923 he wrote: “The question of expanding our (Armenian—S.M.) borders can only be resolved by relying on Russia alone, for only Russia can force the Turks to retreat, and this is the only practical way to conquer land; the rest is naivety and self-deceit. So if there is any hope left here, again it rests only on the Bolsheviks…”43

1 See: State Archives of the Azerbaijani Republic (SAAR), rec. gr. 28c, inv. 1c, f. 99, sheet 1. Back to text

2 SAAR, rec. gr. 970, inv. 1, f. 1, sheet 46. Back to text

3 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 970, inv. 1, f. 1, sheets 51-52. Back to text

4 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 970, inv. 1, f. 1, sheets 53-54. Back to text

5 See: J. Gasanov, Azerbaijan in the International Relations System (1918-1920s), Baku, 1993, pp. 89-90 (in Azeri). Back to text

6 See: Azerbaidzhanskaia Demokraticheskaia Respublika. Vneshniaia politika (Dokumenty i materialy), Baku, 1998, p. 42. Back to text

7 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 970, inv. 1, f. 42, sheets 3-4. Back to text

8 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 28c, inv. 1c, f. 99, sheet 96. Back to text

9 See: K istorii obrazovania Nagorno-Karabakhskoi avtonomnoi oblasti Azerbaidzhanskoi S.S.R. 1918-1925. Dokumenty i materialy, Baku, 1989, p. 34. Back to text

10 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 28c, inv. 1c, f. 99, sheet 96. Back to text

11 K istorii obrazovania Nagorno-Karabakhskoi avtonomnoi oblasti Azerbaidzhanskoi S.S.R.., pp. 49-50. Back to text

12 Sh. Mamedova, Interpretatsia totalitarizma. Stalinizm v Azerbaidzhane. 1920-1930, Baku, 2004, p. 163. Back to text

13 See: Dekrety Azrevkoma (1920-1921), Collection of Documents, Baku, 1988, pp. 87-88. Back to text

14 See: Bor’ba za pobedu Sovetskoi vlasti v Gruzii. Dokumenty i materialy (1917-1921), Tbilisi, 1958, pp. 613-614. Back to text

15 See: Russian State Archives of Sociopolitical History (RSASH), rec. gr. 85 “Ordzhonikidze G.K.,” inv. 13, f. 98, sheet 1. Back to text

16 K istorii obrazovania Nagorno-Karabakhskoi avtonomnoi oblasti Azerbaidzhanskoi S.S.R., p. 57. Back to text

17 See: R. Mustafazade, Dve Respubliki. Azerbaidzhano-rossiiskie otnosheniia v 1918-1922 gg., Moscow, 2006, p. 221. Back to text

18 See: See: SAAR, rec. gr. 28c, inv. 1c, f. 99, sheet 102. Back to text

19 Dokumenty vneshnei politiki SSSR, in seven volumes, Vol. II, Moscow, 1958, p. 728. Back to text

20 S.V. Kharmandarian, Lenin i stanovlenie Zakavkazskoi federatsii. 1921-1923, Yerevan, 1969, p. 47. Back to text

21 See: Dokumenty vneshnei politiki SSSR, Vol. III, Moscow, 1959, p. 675. Back to text

22 See: Dokumenty vneshnei politiki SSSR, Vol. IV, Moscow, 1960, p. 711. Back to text

23 See: I. Musaev, Political Situation in the Azerbaijan Regions of Nakhchivan and Zangezur and the Policy of Foreign States (1917-1921), Baku, 1996, pp. 269-301 (in Azeri). Back to text

24 See: Dokumenty vneshnei politiki SSSR, Vol. III, p. 599. Back to text

25 RSASH, rec. gr. 85 “Ordzhonikidze G.K.,” inv. 13, f. 151, sheets 1-7. Back to text

26 See: K istorii obrazovania Nagorno-Karabakhskoi avtonomnoi oblasti Azerbaidzhanskoi S.S.R., p. 74. Back to text

27 See: A.M. Akopian, A.M. Elchibekian, Ocherki po istorii Sovetskoi Armenii. 1917-1925, Yerevan, 1953, p. 178. Back to text

28 See: S.V. Kharmandarian, op. cit., pp. 101-102. Back to text

29 Ibid., p. 103. Back to text

30 K istorii obrazovania Nagorno-Karabakhskoi avtonomnoi oblasti Azerbaidzhanskoi S.S.R., pp. 86-87. Back to text

31 See: RSASH, rec. gr. 85 “Ordzhonikidze G.K.,” inv. 13, f. 98, sheet 1. Back to text

32 See: K istorii obrazovania Nagorno-Karabakhskoi avtonomnoi oblasti Azerbaidzhanskoi S.S.R., pp. 90-92.Back to text

33 See: S.V. Kharmandarian, op. cit., p. 110. Back to text

34 SAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv. 1, f. 96, sheet 63. Back to text

35 SAAR, rec. gr. 379, inv. 40c, f. 16, sheet 5. Back to text

36 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 379, inv. 40c, f. 45, sheet 2. Back to text

37 SAAR, rec. gr. 28c, inv.1c, f. 135, sheet 15. Back to text

38 SAAR, rec. gr. 411, inv.1, f. 54, sheet 25. Back to text

39 See: SAAR, rec. gr. 28, inv.1, f. 84, sheet 3-4. Back to text

40 See: T. M. Zeinalova, From the History of National State-Building in Azerbaijan (1920s-1930s), Baku, 2004, pp. 33, 49 (in Azeri). Back to text

41 See: ZSFSR v tsifrakh. Central Statistical Board of Z.S.F.S.R., Tiflis, 1929, p. 1. Back to text

42 See: I. Musaev, op. cit., p. 328. Back to text

43 Ov. Kachaznuni, Dashnaktsutiun bol’she nechego delat’! Baku, 1990, p. 77. Back to text