By mid-1961, 200,000 Armenians immigrated to Armenia.[14] Between 1962 and 1973, the republic received more than 26,100 settlers.[15]

Not being satisfied by gaining about 20,000 sq.km, carrying out ethnic cleansing, resettling Armenians from abroad and obtaining autonomy status for the mountainous part of Garabagh within Azerbaijan, Armenia didn’t retract its demands of the inclusion of Garabagh – under the pretext of claims on the mountainous part – and Nakhchyvan in Armenia. This led to expulsion of the remaining 200,000 Azerbaijanis in 1988 (apart from Nuvadi village in the Mehri district, the population of which was expelled on 8 August 1991, i.e. within one day) from Armenia.

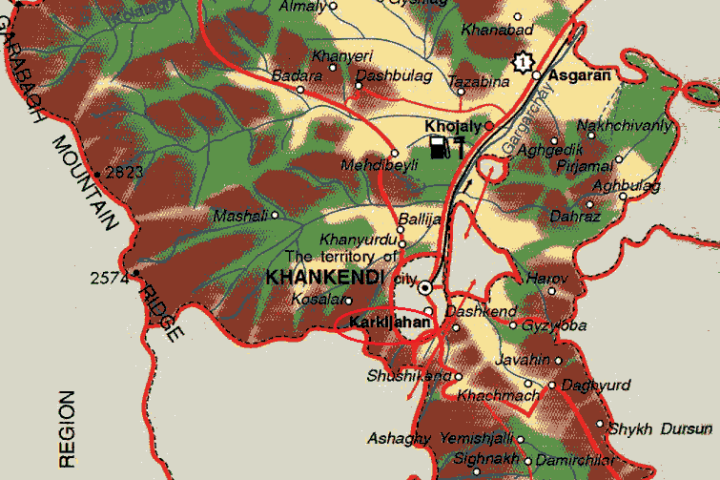

Notwithstanding all the hardships, the consistent movement for independence by the Azerbaijani people culminated in the restoration of the international legal personality of Azerbaijan, after an interval of more than 70 years, in 1991. The independence coincided with the undeclared war of Armenia against Azerbaijan, the active military phase of which began in 1991. Starting with a period of open territorial claims in 1988, it resulted in the occupation of a great portion of Azerbaijani territory: a considerable part of Garabagh (the districts of Shusha, Kalbajar, Lachyn, Gubadly, Zangilan, Jabrayil, Fuzuli, Khojavand, Khojaly, Aghdam and Tartar), as well as 7 villages in the district of Gazakh and the village of Karki in the district of Sadarak and made approximately one out of every eight people in the country an internally displaced person or refugee.

The war against Azerbaijan has been accompanied by a severe blow on its socio-economic sphere and its natural and cultural resources. As a result of the Armenian aggression, Azerbaijani-populated settlements, social and medical buildings, factories and plants, irrigation systems, bridges, roads, water and gas pipelines used by the Azerbaijanis have been destroyed or burnt down. Armenian invaders mostly destroy forests and greens in the areas, which were un- der special protection of the Republic of Azerbaijan, for example, the Bashitchay State Reserve in the occupied Zangilan district. This reserve is the second natural plane (chinar) reserve in the world, and the first in Europe. Some of the Eastern plane trees in the reserve are 1200-1500 years old. At present almost all valuable tree species are illegally exported by Armenia for sale. The richest deposits of mineral resources were also left in the occupied areas. These deposits are being largely and illegally exploited by Armenia.

The war also had catastrophic consequences for Azerbaijan’s cultural heritage both in its occupied territories and in Armenia. The ongoing policy of deliberate destruction of this legacy following the occupation has been and continues to be an irreparable blow to Azerbaijani culture. As clearly demonstrated in the deliberate change of the cultural look of Shusha and other towns and settlements of Garabagh by destroying the monuments and changing architectural features, and making “archeological” excavations, this Armenian policy pursues far-reaching targets of removing any sign heralding their Azerbaijani origins.

Analysis of the 14 years since the declaration of a cease-fire in 1994 shows that the military phase of the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which lasted for almost 3 years, didn’t destroy Azerbaijani monuments to the extent to which this was subsequently done by the Ar- menian authorities. Acts of barbarism are accompanied by different methods of defacing the Azerbaijani cultural image of the occupied territories. Amongst them are large-scale construction works therein, such as, for example, the building of an Armenian church in Lachyn town, the extension of the flight line of the Khojaly airport by destroying the children’s music school, library, social club and infrastructure facilities. Another widespread phenomenon consists of changing the architectural aspects of different monuments like the Saatly mosque and Khanlyg Mukhtar caravanserai in Shusha town, as well as replacing the Azerbaijani-Muslim elements of the monuments with alien ones, such as the Armenian cross and writings, which have been en- graved on the Arabic character of the 19th century Mamayi spring in Shusha town. Azerbaijani mosques have been turned into stable for different animals, including pigs.

As for the fate of the Azerbaijani historical and cultural heritage in Armenia, those which could survive until the beginning of the conflict were also liquidated afterwards, such as the Damirbulag and Goy mosques of Yerevan. Thus, the former was razed to the ground, while the latter has been “restored” and presented as a Persian mosque. The mosques and other Azer- baijani monuments in other places of Armenia have also shared the same fate as the above- mentioned two, together with ancient or modern Azerbaijani cemeteries and toponyms of Azerbaijani origin, which have been erased from present-day Armenia.

References:

- Н.Н.Шавров, Новая угроза русскому делу в Закавказье: предстоящая распродажа Мугани инородцам (СПб: Типография Редакции периодических изданий Министерства Финансов, 1911), с. 59-60.

- See История армянского народа (Ереван: Издательство Ереванского Университета, 1980), с. 268.

- See Кавказский календарь на 1917 год (Тифлис: Типография Канцелярии Наместника Е.И.В. на Кавказе, 1916), с. 219.

- See ibid., pp. 220-221. 5 Епископ Макар Бархударянц, Арцах – НАИИАНА инв N1622, 2010, c.

- 5-6.

- See State Archive of Political Parties and Social Movements of the Republic of Azerbaijan, f. 970, in. 1, f. 1, p. 51.

- See Г.Галоян. Борьба за Советскую власть в Армении (Москва: Государственное издательство политической литературы, 1957), с. 92.

- See Ц.П.Агаян. Великий Октябрь и борьба трудящихся Армении за победу Советской власти (Ереван: Издательство Академии Наук Армянской ССР, 1962), с.174; Е.К.Саркисян. Экспансионистская политика Османской империи в Закавказье накануне и в годы первой мировой войны (Ереван: Издательство Академии Наук Армянской ССР, 1962), с. 365.

- See История армянского народа, с. 283.

- See Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, Paris Peace Conference, 1919. Volume IX (Washing- ton, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946), pp. 899 & 901.

- See ibid., p. 904.

- See История армянского народа, с. 336.

- See ibid., p. 366.

- See Документы внешней политики CCCP. Государственное издательство политической литературы (Москва, 1962), т. 6, прим. 33, с. 611.

- See История армянского народа, с. 418.