4. The international aspects of the conflict

Owing to the conflicts, the processes of globalization embraced the South Caucasus region sooner than other parts of the post-Soviet space. The presence of oil aggravated the conflicts turning them into an international problem. The consequences of these processes have barely been studied and hereby we endeavour to outline the scope of problems that emerged in consequence of this.

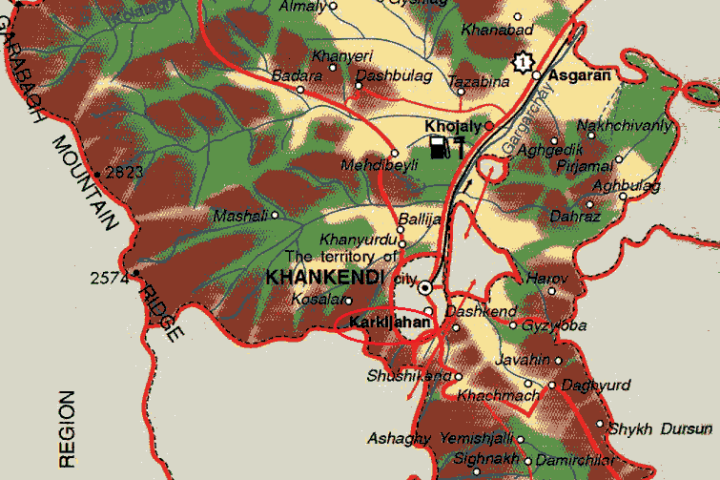

Since May 1994, a fragile armistice has been preserved in the region. In the course of this armistice the sides have failed to find acceptable variants of solving the inter-ethnic conflict. Had the region been faced with other geopolitical conditions and had Azerbaijan not had the strategic resources of energy (oil and natural gas), the conflict would have probably been settled long ago. However, several large countries and the world superpower, the United States, see the region as in their “vitally important, strategic” interests, entangled in a complex web of contradictions and not always clearly stated8. On the other hand, Russia, which has been trying to determine its political priorities in the South Caucasus for years, does its best to recover the influence that the USSR had in the region. Iran, worried by a possible entry of the US and NATO into the region more than by anything else, resists in every possible way the inflow of Western investments and the formation of a new center of world economic development, which implies connecting Western Europe with the Far East by means of communications and oil-gas pipelines. Despite several quite real contradictions, the Russian Federation and Iran at the present moment have to become tactical allies, striving to oppose the grandiose ambitions of the West to include the vast regions of the South Caucasus and Central Asia (CA) into its sphere of political and economic influence. The three recognized republics of the South Caucasus are assigned different roles by these opposing countries, but it is clear that a full-scale realization of anybody’s ambitions in the region is possible only if these republics are included in a common geopolitical space.

It may seem paradoxical that Armenia, which has the most significant Diaspora in the West, became an ally of Russia and, as a matter of fact, a conductor of its political interests in the region. Despite the fact that it was on the insistence of the Armenian Diaspora that the US introduced in 1992 sanctions against Azerbaijan set forth in Section 907 of the “Freedom Support Act” (making Azerbaijan the only country in the CIS deprived of US government assistance until the 9/11 events), the Republic of Armenia continues to believe that it can realize its goals only through its alliance with Russia. The grounds for such a choice centers on the coincidence of interests of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Armenia: the former strives to turn the Republic of Armenia into a military-strategic outpost of its influence; the latter sees in the Russian Federation a protector from its traditional foe – Turkey, which unequivocally defends the position of the Azerbaijan Republic in the Karabakh conflict. The Azeri side contends that in the mid-90s the Russian Federation granted to the Republic of Armenia heavy armaments worth 1 billion US dollars (including missiles capable of reaching Baku). There is a fear in Azerbaijan that all this military power is intended to deliver a new blow against Azerbaijan to seize new territories having strategic importance for the functioning of the Baku-Supsa (Georgia) pipeline and the new Baku-Ceyhan (Turkey) oil pipeline. Those in Armenia say that one can hardly agree with such a contention, as close by, there is an equally strong army of another country concerned – Turkey.

Generally, Turkey’s relations with the countries of the region are an important aspect in the international “dimension” of the situation in the South Caucasus. Turkey itself, as a large and powerful regional state, is naturally seeking to strengthen its influence in the newly independent countries of the region. Besides, as both a NATO member and the main regional ally of the US, Turkey is objectively taking part in the competition (albeit somewhat weakened and indistinct lately) between Russia and the West for influence in the South Caucasus. However, the positions of Turkey in the region are being consolidated more slowly than it might be expected on the face of it. The reason is the existence of the Karabakh conflict. Having common ethnic characteristics with Azerbaijan, Turkey took a tough pro-Azeri position in this conflict. The matter is not in the material or military aid. More important is the psychological aspect of such support consolidated by internal political realities in both Turkey and Azerbaijan. All too often, the media (Armenian and foreign) have expressed the opinion that but for the factor of Turkey, the political elite of the Azerbaijan Republic would probably have been more inclined to compromises. One way or another, Turkey factually imposed economic sanctions on the Republic of Armenia: closed the common border and refused to trade directly with it. This was done in the interests of a third country – Azerbaijan, and became quite a rare case in the history of the last decade. Perhaps the only comparison it bears is with Iraq’s unilateral embargo in April 2002 on oil exports in support of the Palestinian struggle against Israel. Add to it such a factor as the traditional mutual wariness of the Armenians and Turkey constantly fuelled by the problem of qualifying the events of 1915. The Armenians presume that, in essence, the problem is whether these events should be called “genocide”, for nobody in Turkey itself denies that hundreds of thousands of Armenians perished at that time. Those in Turkey consider that the Armenian estimation of 1.5 million victims to be exaggerated and stress that no less Turks and Kurds than Armenians perished at those times. As a result, the border between the Republic of Armenia and Turkey became the second line of tension after the border dividing the Republic of Armenia and the Azerbaijan Republic (however, let us make it clearer and say that in the latter case it would be more appropriate to speak not about the borders, but about the lines of opposition, at least for the simple reason that as a result of the military operations those lines became different from the official borders).

Meanwhile, the Republic of Armenia is going through another stage of its attempts to limit the influence of the Russian Federation or at least to find a parity with the influence of the West (the USA). This is largely promoted by the foreign political concept that Armenia adopted, the so-called “complementarism”, presupposing a possible removal of discrepancies between the interests of Russia and the West in the region. It is typical that these efforts are undertaken by the forces that came to power on the wave of criticism of the position of former president Levon Ter-Petrosyan, who was removed from power in 1998 after his attempts to solve the NK problem in accordance with the statement of the OSCE Chairman at the Lisbon Summit9.

Even official sources in the Republic of Armenia acknowledge that about one million people left the country as emigrants and in search of work, although some independent experts think that this number is understated10. The number of Armenians who left NK is also considerable. So, the vast territories including the occupied ones are practically desolate. But in the neighboring countries – the Azerbaijan Republic (about 2 million people left the country) and Georgia (about 1.5 million left) – the situation is just as sorrowful, so it is time to speak about a demographic disaster in the region, since the majority of those leaving their countries are young men of reproductive age. The economic stagnation of the Republic of Armenia, lacking vast raw materials and energy resources, prods its political leadership towards solving the conflict and joining the strategic projects on reforming the region, which, possibly, contradicts the interests of the Russian Federation (if it is possible to speak about a fully developed concept of the Russian policy in the South Caucasus at all).

On the other hand, during recent years, the OSCE Minsk Group (MG) has been more and more actively putting forth a thesis in favor of developing economic cooperation between Armenia and Azerbaijan before a political solution to the problem is found. Obviously, the West sees not only the possibility of removing tension in the region and expanding its investment programs in this way, but also a certain decrease in the military-political influence of the Russian Federation in the region. However, similar proposals are always discarded by Azerbaijan which thinks that any cooperation with the country occupying its territory is impossible prior to the settlement of the conflict. This will be dealt with in more detail below.

Under the circumstances, Georgia, which could assume an intermediary mission between the two countries of the South Caucasus, has itself, not without Russia’s involvement, been plunged into the depths of inter-ethnic conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia and by the latent confrontations in Ajaria and Javakheti. It should be noted that unlike the Azerbaijan Republic, which is consistently advised to seek a solution to its problem only by peaceful negotiations, in the case of Georgia, the West silently admits the possibility of a military solution to the problem of its territorial integrity (nevertheless, the attempt of Georgia to reach a military solution of the South Ossetia conflict was condemned by the West). In any event, Georgia and the Azerbaijan Republic today are strategic allies and strive to jointly reduce the presence and influence of Russia in the region. (Time will show if this aim remains unchanged after the change of the two countries’ leaders.) The formation of the GUUAM Union (comprising Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Moldova, though recently Uzbekistan announced its quitting this organization) has thus become one of the forms of such activities clearly directed against Moscow’s military-economic dictate. The recent decision of the US to invest $45 million into this organization may give it a fresh impetus for development.

The levels of the Karabakh conflict: from local to global scale (part 4)

[no_toc]