Sergo Orjonikidze: “The Karabakh Issue is a Matter of Honor for All the Soviet Republics and Should Be Resolved Once and For All”

Protocol No. 6 of the plenum of the Caucasian Bureau clearly indicates that Nariman Narimanov was also present: point 1 of the agenda was related to his opponents. Sarkis [Sarkisov] was promptly fired, while the C.C. Az.C.P. (B.) was suggested that, without disrupting the smooth functioning of the Baku Committee, G. Jabiev, R. Akhundov, S. Agamirov, O. Shatunovskaya, and G. Lordkipanidze be moved to new posts.35[35]

Nariman Narimanov, who remained the only member at the 3 June sitting, preferred not to comment on the decision of the Caucasian Bureau. He decided to continue fighting with the help of republican structures. On the other hand, the secret decision of the Caucasian Bureau on the Zangezur issue signed by Yu. Figatner and stamped by the Caucasian Bureau was sent to all the Bureau members, including N. Narimanov in Baku.36

The absence of Azerbaijan’s prompt response and protest against the illegal inclusion of the article relating to Karabakh encouraged the Armenians to intensify their claims on Karabakh and start moving in this direction.

What caused the hasty and legally untenable actions designed to transfer Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia? What was behind Armenia’s actions and the decision of the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) in May-June 1921?

The answer is simple. On 15 June, the commission on border problems among the Transcaucasian republics was to meet in Tbilisi. On 2 May, 1921, the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau set up a commission of representatives of the three republics headed by Sergey Kirov to delimitate the administrative borders.37

On the eve of the Tiflis meeting, the Caucasian Bureau (by its decision of 3 June) and the Armenian government (by a decree of 12 June) wanted to confront Azerbaijan with the accomplished transfer of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

On 26 June, the CPC of Azerbaijan discussed A. Karaev’s report about his trip to Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhchivan and decided that the Armenian claims to Nagorno-Karabakh should be studied and summarized in a detailed report to the Council. A group of three (Shakhtakhtinsky, Vezirov, and Aliev) was set up to cope with the task. It was decided to suspend the powers the Armenian government had extended to Mravyan until the group had completed its report and to inform G. Orjonikidze, Chairman of the Armenian Revolutionary Committee A. Myasnikov, Navy Commissar of Azerbaijan A. Karaev, and A. Mravyan of this decision.38

On 27 June, Narimanov, in fulfillment of the decision, informed G. Orjonikidze and A. Myasnikov by telegraph that the CPC of Azerbaijan had unanimously deemed the unilateral decision on Nagorno-Karabakh passed by the Armenian Revolutionary Committee without discussion at the CPC of Armenia and the arrival of A. Mravyan in Nagorno-Karabakh as envoy extraordinary of Armenia to be an unprecedented political and tactical mistake. It was also requested that Mravyan be immediately recalled.39

Four days after Kirov had been elected First Secretary of C.C. of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan it was urgently requested to urgently deliver Karaev’s report to the C.C. of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan no later than 03:00 p.m. of 29 July.40

Business Manager of the CPC of Azerbaijan A. Shirvani replied that in the absence of a verbatim report, it was impossible to reconstruct what Karaev had said at the meeting.41

On 27 June, a joint sitting of the Politburo and Orgburo of the C.C. of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan discussed the problem of borders between Azerbaijan and Armenia and dismissed the Nagorno-Karabakh issue raised by A. Bekzadyan as untenable in view of the region’s obvious economic bias toward Azerbaijan. Likewise, it was administratively and economically untenable to divide the localities with Armenian and Azeri populations between the two republics. On the basis of Narimanov’s declaration, involving Armenian and Muslim villagers in wide-scale Soviet construction was suggested as the only answer. It was also suggested that all discussions be discontinued until relevant information had arrived from Tiflis. Even before the sitting adjourned, A. Shirvani, instructed by Narimanov, informed Huseynov in Tiflis of this decision.42

His message said in part: “The Council of People’s Commissars has agreed with the decision. Comrade Narimanov asked me to inform you that the question must be resolved in this way, otherwise the Council will divest itself of all of its responsibilities, since if this is the way Soviet Armenia wishes to make a good impression on the Dashnaks and the non-party masses, we should bear in mind that by the same token we will be reviving anti-Soviet groups in Azerbaijan similar to the Dashnaks.”

At this point Narimanov took the receiver and said to Huseynov: “Tell them that this is the unanimous opinion of Politburo and Orgburo. My declaration, to which they refer, merely said, ‘Nagorno-Karabakh is being granted the right to free self-determination.’”

Huseynov, in turn, promised to personally supply the details of the Tiflis process and deemed it necessary to warn that “our decision will be coolly received.” He reminded Narimanov of the talk that had taken place the day before, saying: “Yesterday I spoke to Comrade Sergo, who minced no words: the Karabakh issue is a matter of honor for all the Soviet republics and should be resolved once and for all. These were his exact words, which I quoted to you yesterday.”

Nariman Narimanov said: “Today we sent you a telegram, with copies to Sergo, Myasnikov, and Karaev, to inform you that Comrade Mravyan has been recalled from Karabakh.”

Mirza Huseynov deemed it necessary to point out that the situation was far from simple and that a way out should be sought for and found. He said: “I think we should first discuss in detail why, on the one hand, the CPC of Armenia is making one declaration and sending its commissar extraordinary to Karabakh, without informing us so to speak, although our Armenian comrades insist that this is being done with our knowledge and consent. While on the other hand, we are sending them a telegram that essentially annuls their decisions. I am at a loss. I think that the question should be discussed more than once—there is no other solution. Right now I shall consult with Sergo and contact you once more before my departure.”

Narimanov asked Huseynov to tell Orjonikidze that “if he familiarizes himself with the material we have at our disposal, he will also object to all of this. You will bring all the documents with you to Tiflis and then it will become clear that our Armenian comrades are only thinking about the territory and are not concerned about the wellbeing of the poorest Armenian and Muslim groups or about strengthening the revolution.”43

The question is who allowed the Armenians to speak in the name of the Azeri leaders? Mirza Huseynov, who said that “this is being done with our knowledge and consent,” hinted at Narimanov’s failure to speak out at the meeting of the Caucasian Bureau on 3 June. His passivity negatively affected the course of the discussion of the Karabakh issue. Later, however it turned out that it had been Orjonikidze and Kirov who gave the Armenians this permission. Having concentrated real power in the Caucasus, they were looking for ways to transfer Karabakh to Armenia. It was they who handed Narimanov the telegram on 26 June with Bekzadyan’s idea about dividing Karabakh on national-ethnic grounds. The telegram read: “If you want to know our opinion, it is the following: to smooth out the friction and establish genuinely friendly relations when dealing with the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, we should be guided by the principle that none of the Armenian villages should be united with Azerbaijan, just as none of the Muslim villages should become part of Armenia.”44

The same day, 27 June, Huseynov, on Narimanov’s instructions, moved the issue to the Caucasian Bureau, which ruled the following: “An extraordinary plenum of the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) must be convened immediately. The following telegram should be sent to comrades Narimanov and Myasnikov: ‘The Presidium of the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) suggests that when you receive this you must immediately depart to attend the extraordinary plenum of the Caucasian Bureau to discuss delimitation of the republics. There are six members of the Caucasian Bureau in Tiflis; if you fail to arrive, their decision will be considered final, therefore we insist that you go there at once.’”45

On 28 June, the CPC met once more under N. Narimanov’s chairmanship. Myasnikov’s Declaration, which proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh part of the Armenian S.S.R., was declined; the meeting discussed the possibility of recalling Mravyan, extraordinary representative of Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh. The meeting registered that “in view of Comrade Narimanov’s planned trip to Tiflis, where the question will be discussed by the Caucasian Bureau, the decision of the Politburo and Orgburo of 27 June, 1921 on this issue should be taken as the basis.”46

The intensified Armenian claims to the mountainous part of Karabakh forced Chairman of the Shusha Uezd Executive Committee B. Buniyatov to send Narimanov and People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs G. Sultanov a report on the Situation in the Shusha Uezd, in which he wrote: “The Armenian population (of Nagorno-Karabakh.—J.H.) showed no intention of separating themselves from the Az.S.S.R. because, first, the people know that if they are cut off from the valley they will perish, second, that they will get nothing from impoverished and starving Zangezur except for circulars, and, third, that as part of the Az.S.S.R. they will speak with a strong voice and with the hope that their demands will be promptly satisfied; this will never happen in the Armenian S.S.R…. What the Armenians are saying about being stepchildren in the Az.S.S.R. is explained by the tactless and inappropriate behavior of some of the officials.”47

Why Are the Armenians Falsifying the Well-known Documents of the Caucasian Bureau Relating to Nagorno-Karabakh and Implicating Stalin?

The famous sitting of the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) of 27 June, 1921 never considered the historical and ethnographic aspects; the decision was based on Karabakh’s economic pull toward Azerbaijan.

On 4 July, however, at another plenum of the Caucasian Bureau attended by Stalin, Kirov (future head of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan) and Orjonikidze (the republic’s curator) voted for the following resolution: “To include Nagorno-Karabakh in the Armenian S.S.R. and limit the plebiscite to the mountainous part.”48

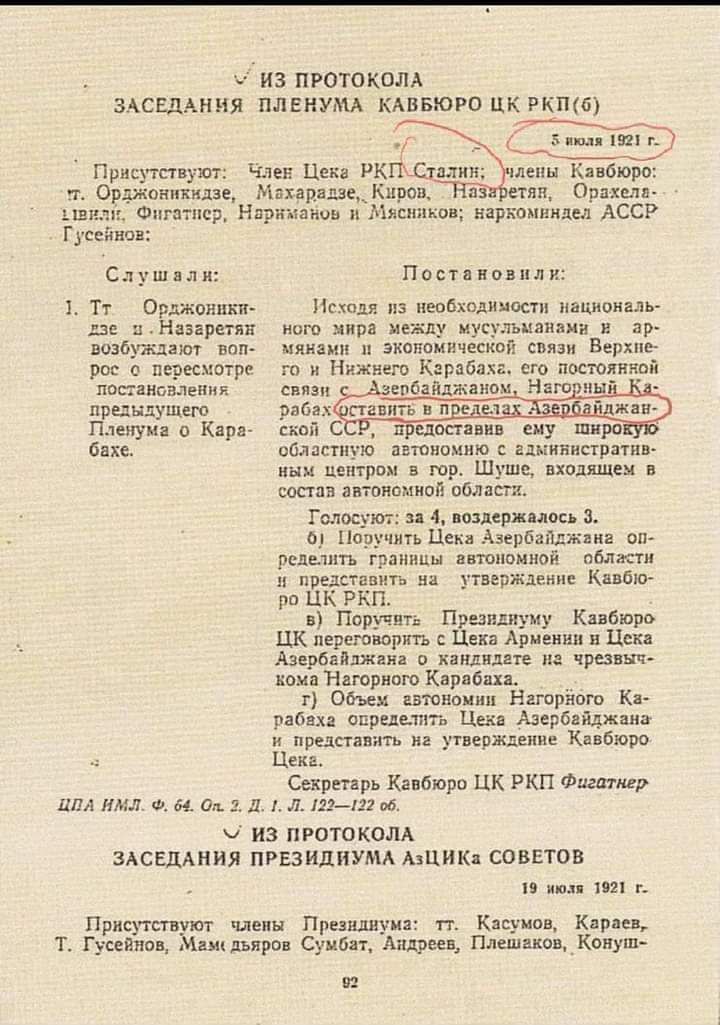

The plenary session was attended by member of the C.C. R.C.P. Stalin and members of the Caucasian Bureau Orjonikidze, Makharadze, Narimanov, Myasnikov, Kirov, Nazaretyan, Orakhelashvili, and Figatner. The discussion revealed two opposite opinions.

The participants were invited to vote for the following:

(a) Karabakh should remain part of Azerbaijan (Narimanov, Makharadze, and Nazaretyan voted “for”; Orjonikidze, Myasnikov, Kirov and Figatner, “against”;

(b) The plebiscite should be carried out throughout the entire territory of Karabakh among the Armenians and Muslims (Narimanov and Makharadze voted “for”).

(c) The mountainous part of Karabakh should be joined to Armenia (Orjonikidze, Myasnikov, Figatner, and Kirov voted “for”).

(d) The plebiscite should be carried out only in Upper Karabakh, that is, among the Armenians (Orjonikidze, Myasnikov, Figatner, Kirov, and Nazaretyan voted “for”).49

The protocol contains a note: Comrade Orakhelashvili was absent when the vote on Karabakh was taken. This was a much more honest position than that of future Secretary of the C.C. of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan Kirov and Orjonikidze, who repeatedly demanded in his telegrams to Lenin and Chicherin that both the valley and the mountainous part of Karabakh be left in Azerbaijan. They voted “for” on the two last points.

The adopted decision violated Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

This made people wonder why Orjonikidze and Kirov, who several months earlier “could not imagine Azerbaijan without Karabakh,” changed their minds in June 1921 and voted against Azerbaijan at the 4 July sitting of the Caucasian Bureau. Were they guided by the Center’s secret instructions?

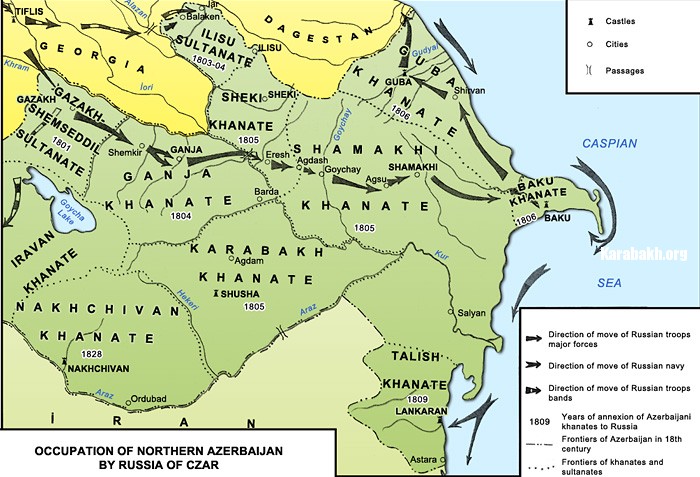

Here is an explanation: the Moscow Treaty of 16 March, 1921 between Soviet Russia and Turkey (with a point which preserved Nakhchivan within Azerbaijan) turned Nagorno-Karabakh into a target of secret and then open discussions at the Caucasian Bureau in June-July 1921 and triggered attempts to transfer Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia by force.

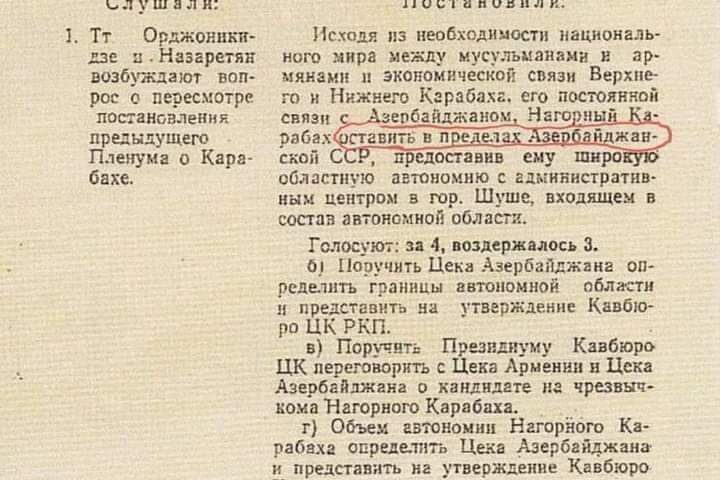

The decision of the Caucasian Bureau of 4 July was frequently falsified and misinterpreted; Academician T. Kocharli has written the following on this score: “The Armenian authors performed a ‘minor’ operation by replacing the verb ‘include’ with the verb ‘leave in’.”50

Nariman Narimanov stated resolutely that “because the Karabakh issue is so important to Azerbaijan, I believe it necessary to transfer the final decision on it to the C.C. R.C.P.”51 It was thanks to his protest that the meeting arrived at the following decision: “Since the Karabakh issue has caused serious disagreements, the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) believes it advisable to transfer the final decision to the C.C. R.C.P. (B.).”52

This meant that the same sitting discussed the Karabakh issue as Point 5 of the agenda; the decision passed by a majority vote after Narimanov’s statement (Point 6) annulled the previous results.

This issue was never discussed in the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) because, first, Orjonikidze had renounced his previous erroneous position and, relying on Nazaretyan, demanded that the decisions of the previous plenary session on Karabakh be revised.53

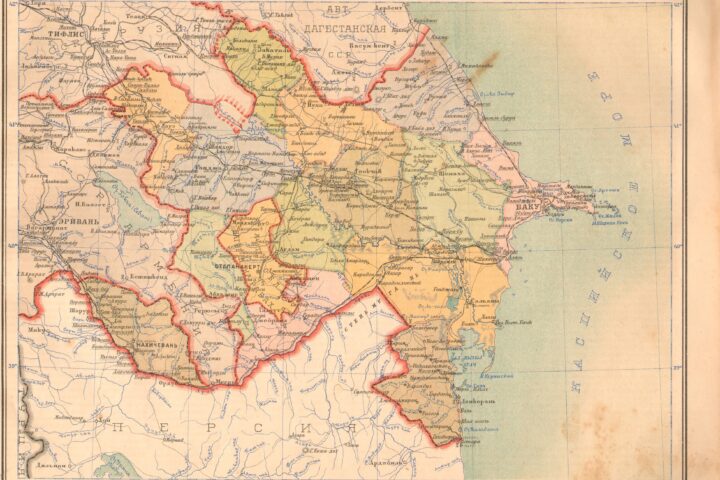

On 5 July, the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau adopted the following decisions on Point 2 of the agenda in view of N. Narimanov’s firm position and G. Orjonikidze’s retreat from his previous stand:

(1) proceeding from the need to maintain national peace between the Muslims and the Armenians, the economic ties between Upper and Lower Karabakh, and its constant contacts with Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh should be left within the Azerbaijan S.S.R. with broad regional autonomy and its administrative center in the town of Shusha, which belongs to the autonomous region;

(2) the C.C. of Azerbaijan should be instructed to identify the boundaries of the autonomous region and present the results to the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) for approval;

(3) the Presidium of the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. should be instructed to talk to the C.C. of Armenia and the C.C. of Azerbaijan about a candidate for the post of commissar extraordinary of Nagorno-Karabakh;

(4) the C.C. of Azerbaijan should be instructed to identify the volume of rights of the autonomy of Nagorno-Karabakh and present the result to the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. for approval.54

When commenting on the repeal of the first “fair decision” on the Nagorno-Karabakh, the Armenian side referred to Stalin’s unexpected arrival in Tiflis, who had allegedly pulled the strings for the Azeris in his usual manner.

Why do the Armenian historians who falsify the historical documents of the Caucasian Bureau implicate Stalin in the “transfer” (their favorite term) of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan? Because the crimes perpetrated under Stalin give the Armenians a chance to present themselves as victims of the totalitarian regime and create the semblance of “fairness restored.”

The Armenian authors and politicians who ascribe the transfer of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan to Stalin’s decision are courting the world public for approval since “it has become fashionable to heap the guilt for all misfortunes on Stalin.”55

In his publication of 1989, Doctor of Philosophy Grant Episkoposyan of Moscow State University, for example, never hesitated to distort the facts and describe Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Armenia transferred to Azerbaijan on Stalin’s instructions.56

Prof. A. Karsetsi, who did not bother to look into the protocols of the Caucasian Bureau, wrote in his book Konflikty mezhdu narodami i puti ikh preodoleniya. K probleme Nagornogo Karabakha (Conflicts between Peoples and Ways to Settle Them. On the Problem of Nagorno-Karabakh), where he claimed to present the latest findings, that “Stalin arrived from Nalchik, where he had been on leave at the time, and supported Narimanov’s demands, contrary to what he had written earlier in his article ‘Da zdravstvuyet Sovetskaya Armeniya!’ (Long Live Soviet Armenia!), which appeared in Pravda on 4 December, 1920. His opinion, alas, proved to be decisive; Nagorno-Karabakh was transferred to Azerbaijan.”57

Another publication issued by the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian S.S.R. (Nagorny Karabakh: istoricheskaya spravka) likewise heaps the blame on Stalin: “The decision of 5 July, 1921 was imposed by Joseph Stalin.”58 It should be said that the book is a result of the joint efforts of prominent Armenian historians who know why Nagorno-Karabakh was transferred to Azerbaijan.

Protocols No. 11 (the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau of 4 July) and No. 12 (the 5 July session) provide an absolutely clear picture. Stalin, who was present at both sessions, said nothing about Karabakh. Protocol No. 8 of the plenary session of the Caucasian Bureau of the C.C. R.C.P. (B.) of 2 and 3 July is kept together with the protocols of 4 and 5 July in the same record group. Any impartial researcher will discover Stalin’s name at the top of the list of those present at these plenums.59

It was Addendum to Protocol No. 8 that registered “the fact of the appearance of nationalist ‘Communist’ groups in the Communist organizations of the Transcaucasus, which were fairly strong in Georgia and Armenia and weak (in terms of their numbers and quality) in Azerbaijan.”60

The results of the discussion of the Zangezur (3 June, 1921) and Nagorno-Karabakh (4-5 July) issues were caused by a wave of Communist nationalism in Armenia raised by the fact that the Moscow Treaty (March 1921) between Soviet Russia and Turkey had registered the status of the Nakhchivan region.

On 15 April, 1921, People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of Armenia A. Bekzadyan (who headed the Armenian delegation at the Moscow talks) sent a long letter of protest to Chicherin in which he accused Soviet Russia of failing to protect the interests of the Armenians. The letter said: “The Armenian delegation finds it very important to point out that the Turkish delegation at the conference acted as a protector and defender of the Muslim population of the Transcaucasus and of the interests of Soviet Azerbaijan in particular.”61

People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs A. Bekzadyan was concerned about the fact that Turkey had managed to retain Nakhchivan, a border point of great importance for its safety in the east, within Azerbaijan.62 He deemed it necessary to stress that “the conference’s decision on the Nakhichevan and Sharuro-Daralagez issues deprived Armenia of the possibility of administering Zangezur, which belongs to it, in a normal way.”63

Georgy Chicherin wrote a letter to Saak Ter-Gabrielyan, who represented the Soviet government of Armenia, informing him of the above, by saying that he was amazed by Bekzadyan’s attempt to justify what the Armenian delegation had been doing at the Moscow conference and push the guilt onto the Russian delegation.

He wrote that the Armenians with whom he had been communicating were well-aware of the conference’s main aim and had never complained of its decisions.64

Chicherin sent a more or less similar telegram to Boris Legran in Tiflis, which said: “I strongly object to the way Bekzadyan is trying, first, to heap the guilt on the Russian delegation and, second, to purge the Armenian delegation of accusations in front of readers or listeners, of whom I know nothing, by distorting the facts and suppressing information of which the Armenian delegation was well aware.”65

The Armenians resorted to blackmail of this sort to be able to take advantage of an opportune moment (in the context of the closed discussions of the Moscow Treaty) to appropriate Karabakh and pull the Center to their side. The Armenian leaders obviously wanted Karabakh as a compensation of sorts.

The Nagorno-Karabakh issue was discussed once more on 5 July at the insistence of Orjonikidze and Nazaretyan; some of the Armenian authors, however, wrote (for obvious reasons) that it was Narimanov, not Nazaretyan, who together with Orjonikidze put the question back on the agenda.66

In their joint article, which appeared in Moscow, V. Zakharov and S. Sarkisyan revived the erroneous statement that Nagorno-Karabakh had not been transferred to Azerbaijan until 5 July.67

It is a well-known fact, however, that Stalin had been in Tiflis since the end of June, therefore his surprise arrival on 5 July is nothing but a later invention. He came to Georgia to replace more or less independent Philip Makharadze, who had quarreled with Orjonikidze, with more pliable Budu Mdivani.